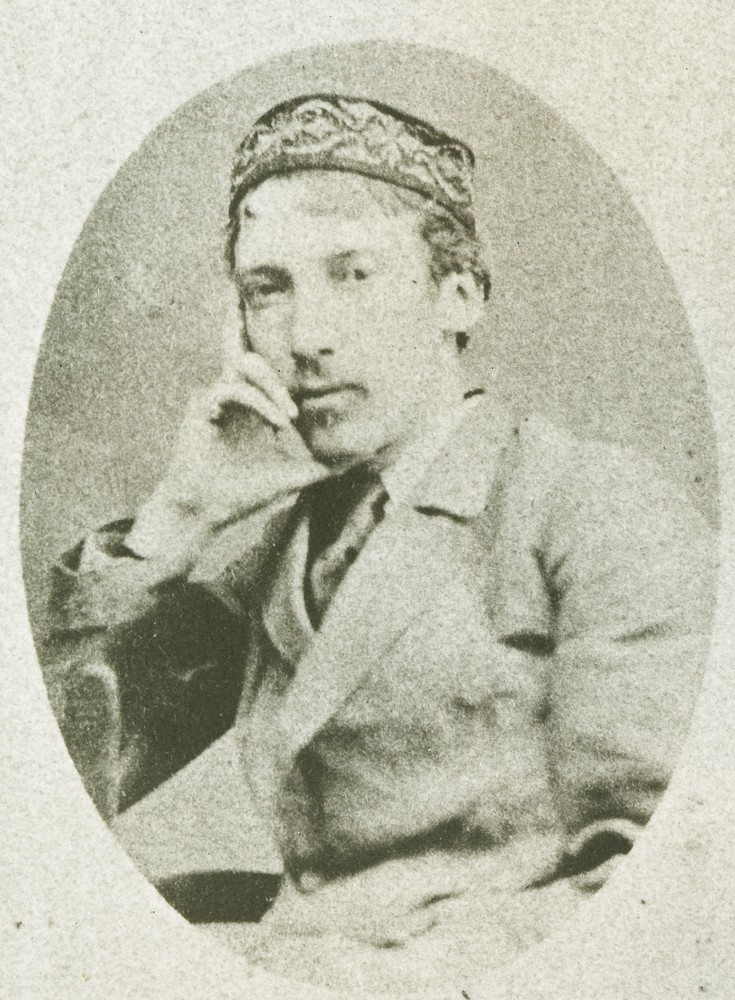

Stevenson in Homburg, 1862

Stevenson visited Germany on four occasions: 1. Homburg (now Bad Homburg vor der Höhe) with his parents, July—August 1862; 2. The following year travelling home from Italy with his parents (Munich—Augsburg—Nuremberg—Frankfurt—Cologne) in May 1863; 3. Frankfurt during his first summer vacation as a student with Walter Simpson, July—August 1872; 4. And finally, for a few days, joining his parents at Wiesbaden in September 1875.

Although steeped in French culture, Stevenson was also attracted to German thought and literature.The 1872 stay in Frankfurt was to improve his German. After the death of his friend James Walter Ferrier, Stevenson remembered that Ferrier, probably in the early 1870s, ‘had [=? had made] a pretty full translation of Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters, which we read together, as well as the second part of Goethe’s Faust, […] he helping me with the German’ (Letters 4: 206). He quotes Goethe and Heine in German several times in his letters from 1872 to 1875 (Letters 1: 289, 316, 403; Letters 2: 13, 72, 81, 122) and read Heine’s love poems together with Fanny Sitwell in the summer of 1873 (Letters 2: 31).

His German experiences are reflected in ‘Will O’ the Mill’ (1878) and Prince Otto (1885) as well as an abandoned essay on Homburg, ‘An Onlooker in Hell’, for a series, planned in 1890, to be called ‘Random Memories’. This latter is now in the NLS (MS 3112, ff. 308-311) and will be published in our Essays V, presently being prepared by Lesley Graham

But to return to his first experience of Germany, not yet twelve years old, in the summer of 1862. A reader of this blog, Thomas Obst, lives a few miles from Bad Homburg and, after some local research, kindly supplies the following facts and images.

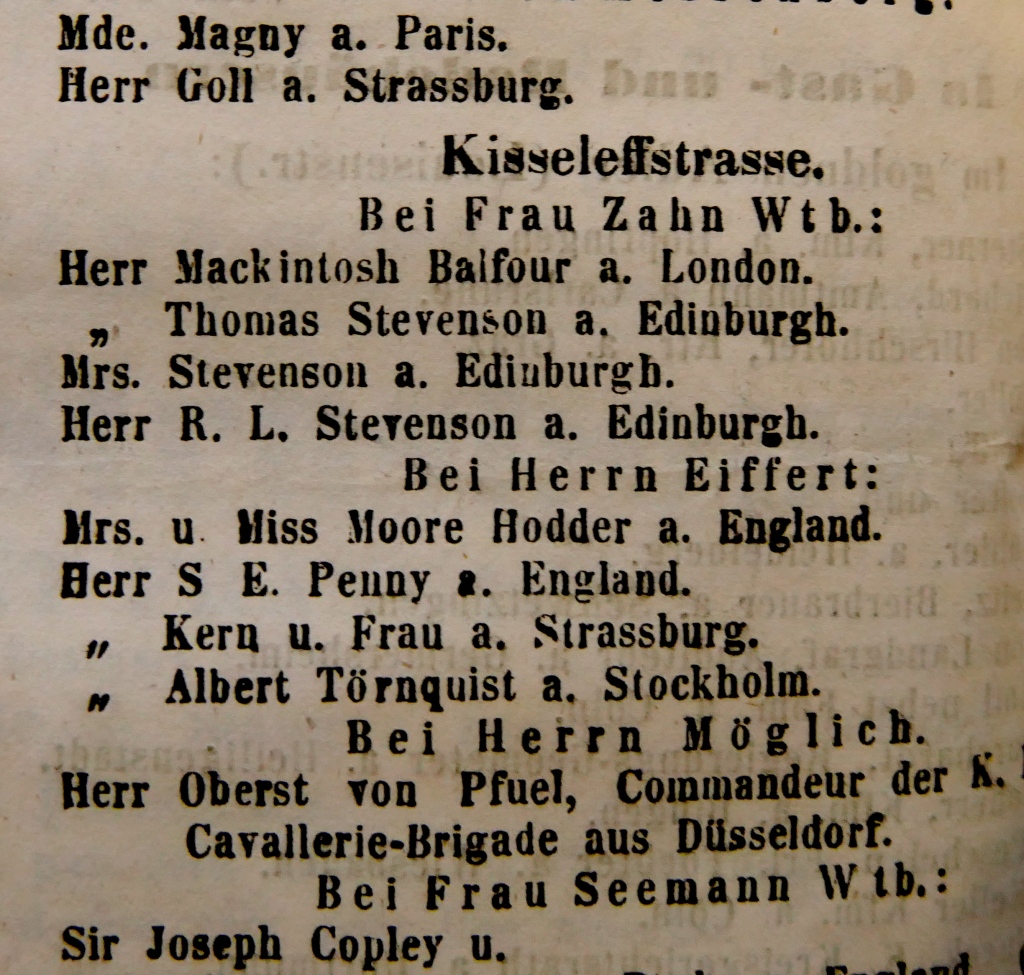

The family were among the new arrivals between 14 and 16 July announced in the Kur- und Bade-Liste dated 17 July 1862. With them was Margaret Stevenson’s brother Mackintosh Balfour, travelling to Homburg, like Thomas Stevenson, for a health cure. They all stayed at the house of the widow Zahn, No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse, a quiet street leading from the main street, Louisenstrasse, to the Park and its Casino.

Almost opposite, on the corner of Louisen- and Kisseffstrasse, was the Russischerhof, or Hotel de Russie, where the Stevenson party took their meals. The building on the corner (right) is certainly the former hotel. Stevenson later stayed in this hotel in 1875: after meeting his parents at Wiesbaden on 2 September, he travelled with them to Homburg and Mainz before leaving them to return to Paris. The Stevenson party is announced in the Homburger Fremden-Liste recording arrivals from 4 to 8 September.

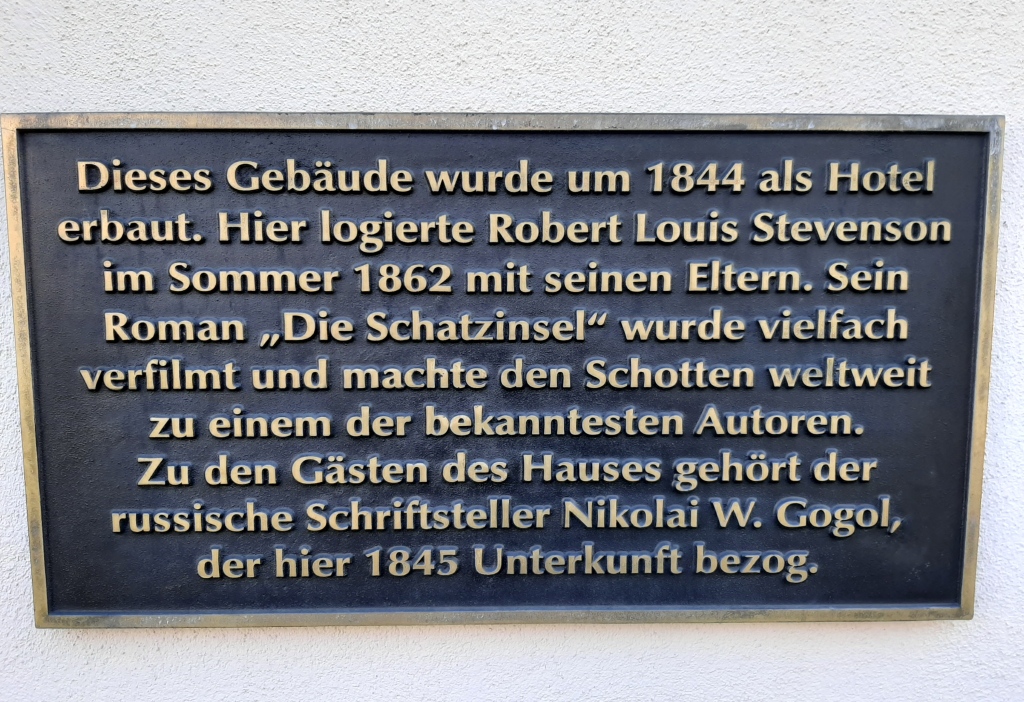

No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse (left) looks more modern. But notice a small dark rectangle on the left of the ground-floor facade. This is a plaque placed there in 2018 commemorating Stevenson’s stay (and also that of Nikolai Gogol), and the inscription starts ‘This building was built in 1844 as a hotel’, which means that the present building, at least in its basic structure and fenestration, is the one where Stevenson and his parents stayed in 1862:

The Stevenson who stayed in Homburg in 1875 was very different from the boy who stayed there in 1862: in 1875 he had graduated from University in July, had already begun publishing literary works in magazines and was in the middle of a formative experience in France living with art students. After arriving in Paris from Germany on 6 September, he proceeded to Barbizon and there met and fell in love with his future wife Fanny Osbourne.

However that early experience in Homburg remained in his memory. In late 1890, searching for subjects for a second series of Scribner’s Magazine essays he sketched out some headings for an essay on his experience of gambling establishements and then wrote a few paragraphs about Bad Homburg. Here, to end, is an extract of part of that text:

[…] I heard first in Homburg the continuous ringing of counted money on the tables of a gaming house. Sitting on the terrace, I became suddenly aware of it with a thrill of the pleasure of hearing not yet forgotten; a fine band of music played there daily, and I have forgot the music; but I think when I come to lie dying, I shall still be able to recal (as I do now) the more delicate concert from within. I thought then already, as I think still today, that there are few sounds to be compared with it in nature. It chanced I was to hear it again and yet again in the course of my vagrant life; and it is a singular thought to me now and in this far away place, that the song of the money is still going on in Europe, like the song of birds, perennial.

Homburg was then near an end; Blanc [François Blanc, director of the Homburg casino] had received a formal warning [gambling was to be outlawed in German in 1872]; he was already (as I was to see next year [1863]) timidly breaking ground elsewhere for another palace of fate [from 1860 in Monaco]; but the original establishment was still humming with gulls and ringing with their money. There were many circumstances to delight a boy abroad for the first time; the taste of mulberries; the sweet water in our house well; the English chapel opening down a long stair into an archway in the old Schloss, the pond with the carp, the vast green rambling ground of forest; the terrace before the Kursaal where the band played and the crowd of visitors walked to and fro in summer raiment […] But the centrepiece of all was that glorified garden-house that sang all day with gold and silver. The barbaric splendour of its decoration, the gold room, the patterns on the tables, the hopping of the roulette ball, the high dry voice of the croupier, the song of the money—and perhaps above all the sense that the place was a temple of wickedness, and that attraction of inverted horror which it is so easy and so dangerous to arouse in children — held me in bondage to the image of the Kursaal itself. Sometimes my father took me in, and I would wander, a twelve-year-old observer, about the crowded tables. The large liveried footmen were an awful joy to me; I had picked up that they served as spies upon the visitors; and I would place myself near one, try to follow the direction of his glances, and thrill all over with the sense of secrecy and peril. […]

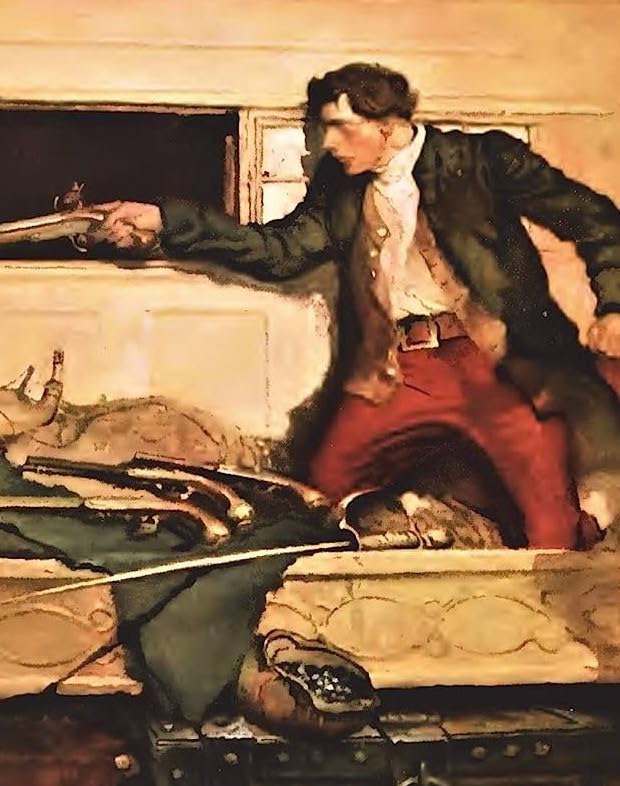

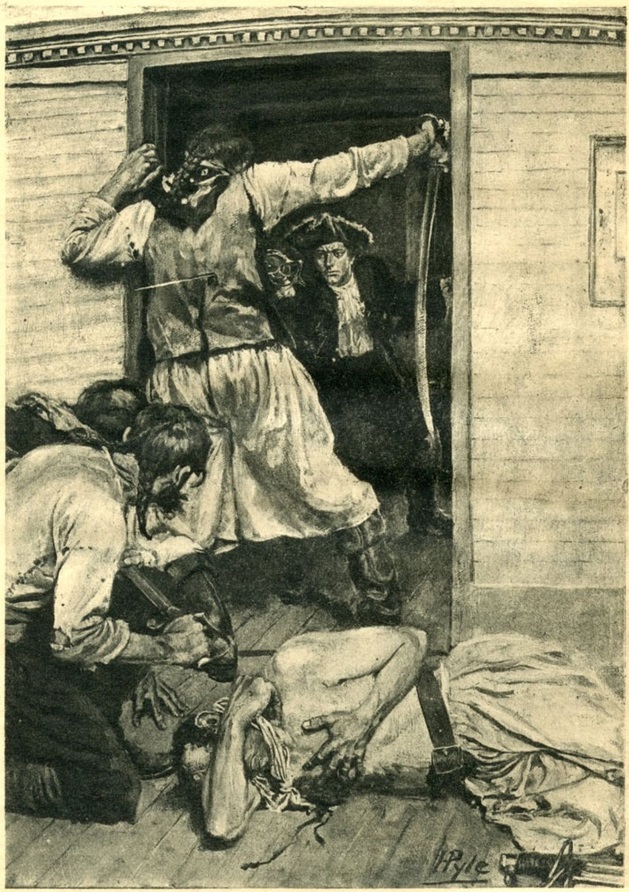

Kidnapped: can we draw a plan of the roundhouse?

There’s no real need to imagine the plan of the roundhouse in Kidnapped: you understand that it’s a single structure on the top deck of the Covenant with doors, windows and a skylight and understand their relative positions. If you can’t work out how the dangerous openings relate to fore and aft, port and starboard, it doesn’t really matter: in a way, it helps contribute to the sense of a confused and rapid action.

However, if you were to prepare an annotated edition of the novel you might want to see if the narrative actually supplies a coherent picture of spaces and their relative positions, and this would help translators, illustrators and authors of other derived works.

The roundhouse is not round. First of all, let’s clear up the name. It is not, as a naive reader might imagine, circular. It’s a cabin, certainly rectangular in plan, built across the afterdeck where the captain and officers eat and sleep. In ch. 9 Stevenson also refers to it as a deck-house.

The name ’roundhouse’ was first used for an aft cabin with curved windows, so originally ’round’ had a meaning; then the word was applied, as here, to a structure of similar function at the aft end of the ship providing accommodation for captain and officers. It’s the same as ‘the raised cabin on the quarter-deck’ in an earlier American pirate novel:

Going aft to the raised cabin on the quarter-deck, the Captain softly opened the weather door, and looking in, said, in a kindly tone … (H. A. Wise, ‘Captain Brand of the Schooner “Centipede” ‘, ch. 1, Harper’s Weekly, Apr. 1, 1860, p. 209)

It has two doors, two windows and a skylight. In ch. 8 we learn that the roundhouse has a skylight in the roof and ‘a small window with a shutter on each side’ — i.e. on each side, on two opposite sides, of the cabin. At this point we don’t know which of the two opposite sides are intended, nor do we learn about the doors.

Later in the chapter Mr Riach seizes the bottle from the table of the inebriated Mr Shuan:

crying out, with an oath, that there had been too much of this work altogether […]. And as he spoke (the weather sliding-doors standing open) he tossed the bottle into the sea.

‘Weather sliding-doors’ is a bit strange (but that’s not unusual for Stevenson): we’d normally say ‘sliding weather-doors’, i.e. solid timber doors protecting the cabin from the weather. (Some readers might think that ‘weather sliding doors’ are doors on the ‘weather side’ of the ship, i.e. the side on which the wind is blowing, but as we’ll see, the two doors are on opposite sides of the cabin.)

In ch. 9 we get the fullest description of the roundhouse:

The round-house was built very strong, to support the breaching of the seas. Of its five apertures, only the skylight and the two doors were large enough for the passage of a man. The doors, besides, could be drawn close: they were of stout oak, and ran in grooves, and were fitted with hooks to keep them either shut or open, as the need arose.

The two doors are on opposite sides of the cabin, as we seen from the following exchange:

[Alan said,] ‘It is my part to keep this door, where I look for the main battle […]’

‘But then, sir’ said I, ‘there is the door behind you, which they may perhaps break in.’

‘Ay,’ said he, ‘and that is a part of your work. No sooner the pistols charged, than ye must climb up into yon bed where ye’re handy at the window; and if they lift hand against the door, ye’re to shoot.’

Are the doors port and starboard or fore and aft? As the open doors in ch. 8 allow Mr Riach to toss Mr Shuan’s bottle into the sea, they must be at the sides, port and starboard.

However, in the preparations for the siege of the roundhouse in ch. 9, it looks as if the doors are fore and aft: the Captain and his followers are in the waist of the ship, i.e.amidships, when Davie hears of their plan to kill Alan and is told to get some firearms for them from the roundhouse without being observed. Davie tells Alan and they prepare for battle. Meanwhile ‘those on deck’, not knowing what is going on, are getting impatient and finally ‘the captain showed face in the open door’.

We might think that the door that Alan defends faces the mid and fore part of the deck, with a secondary door giving access to the extreme aft part of the deck. But the door could be lateral if we imagine the captain and others gathered on one side of the ship and so Alan chooses the door on that side to defend, or perhaps the lateral door chosen by Alan is the main door and the other is only secondary — it’s the obvious door to choose. The Captain shows himself in the doorway with no idea yet of what’s going on; as the door appears to be open, this again makes a lateral position more likely.

.

.

The window that Davie has to guard to have warning of an attack at the opposite door must be on that same side of the cabin. Since the two windows are ‘on each side’, then the other window is on the side of the door defended by Alan, and the other two sides of the cabin have no openings.

The photo of the Cutty Sark (above) shows a deck-house with doors at the side, but other images found on the internet show that there was no design obligation to place them laterally, as is show in the photo on the right.

As a reader I don’t find any difficulty in imagining an indefinite configuration to the roundhouse, with doors certainly port and starboard in ch. 8 and possibly fore and aft in ch. 9 and 10—they could still be port and starboard, but I feel the simple schematic position of Alan’s door is facing forwards, opposed to the captain and his men. The five men with a ‘spare yard’ for a battering ram attacking the other door makes me instinctively think of the aft part of the ship with more space for manoeuvre than a passage running alongside the roundhouse.

So in the end I can’t confidently draw a plan—yet I don’t think it matters. But those are my ideas, if you differ you please leave a comment.

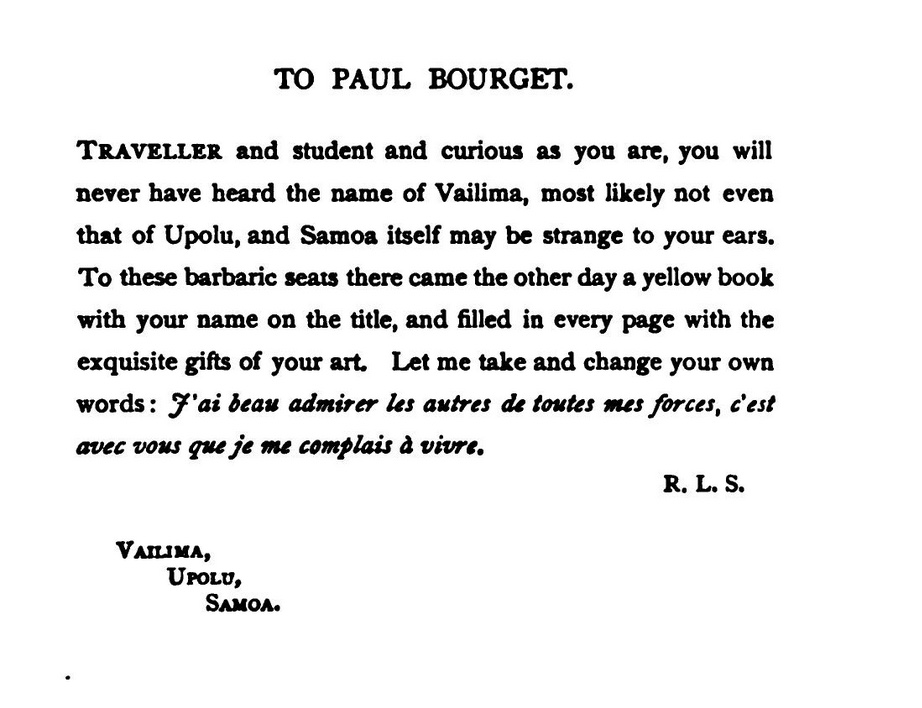

Paul Bourget writes to Stevenson

A post contributed by Katherine Ashley

In 1891, Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Paul Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (1891). The book gave Stevenson a ‘literal thrill’ and he quickly requested more of his works. Bourget (1852-1935) was a poet, novelist, and playwright, but today he is mainly read by literary historians for his astute study of fin de siècle cultural malaise, Essais de psychologie contemporaine (1885). He was also, like Stevenson, a traveller, and it is fitting that Stevenson’s introduction to him was via Sensations d’Italie, a book about Bourget’s travels in Tuscany, Umbria and Puglia.

The reasons for Stevenson’s enthusiasm for Sensations d’Italie are explored in an earlier post; a direct result of his reading is that he dedicated Across the Plains (1892) to Bourget.

To Stevenson’s consternation, Bourget did not immediately respond to the compliment. He complained to Sidney Colvin: ‘ain’t it manners in France to acknowledge a dedication? I have never heard a word from le Sieur Bourget, drat his impudence!’. He was even more to the point in a letter to James. Although the tone is good-humoured, there is an element of hurt and annoyance:

I thought Bourget was a friend of yours? And I thought the French were a polite race? He has taken my dedication with a stately silence that has surprised me into apoplexy. Did I go and dedicate my book to the nasty alien, and the ’n’orrid Frenchman, and the Bloody Furrineer? Well, I wouldn’t do it again; and unless his case is susceptible of Explanation, you might perhaps tell him so over the walnuts and the wine, by way of speeding the gay hours. Seriously, I thought my dedication worth a letter.

As it turns out, Bourget’s case was indeed ‘susceptible of Explanation’: work had prevented him from replying. The excuse seems reasonable, since Bourget spent the first months of 1892 in Rome, which resulted in his novel Cosmopolis (1893). He also published two other books around this time, La Terre promise (1892) and Un scrupule (1893).

Bourget’s contrite reply finally came, enclosed in James’s next letter to Stevenson. The manuscript is kept at Harvard University. It is transcribed and translated here.

Londres, le 3 août 93

Monsieur et cher confrère,

Je suis si coupablement en retard avec vous pour vous remercier de la dédicace du beau livre en tête duquel vous avez mis mon nom que je n’en finirais pas de m’en excuser. Le démon de la procrastination—ce mauvais génie de tous les imaginatifs—m’a joué des tours cruels dans ma vie. Il aurait commis le pire de ses méfaits s’il m’avait privé de la précieuse sympathie dont témoignait votre envoi—et venant de l’admirable artiste que vous êtes, cette sympathie m’avait tant touché. Peut-être trouverez-vous le mot de cette énigme de paresse dans une existence qui six mois durant, l’année dernière, a été celle d’un manœuvre littéraire esclavagé par un engagement imprudent—ce qui n’est rien lorsqu’on a le travail // facile, ce qui est beaucoup quand on ne peut pas « faire consciencieusement mauvais » comme disait je ne sais plus qui.

J’aurais voulu aussi, en vous remerciant, vous dire combien j’aime votre faculté et vision psychologique et comme il m’amuse en vous lisant de trouver entre ce que vous exprimez et ce que je sens sur des points analogues de singulières ressemblances d’âme. Croyez que, malgré mon silence, cette fraternité intellectuelle fait de vous un ami éloigné auquel je pense souvent. Je me réjouis de savoir par Henry James que vous avez retrouvé la santé sous le ciel où vous êtes réfugié. Que je voudrais pouvoir espérer qu’un jour nous nous rencontrerons, et que nous pourrons de vive // voix échanger quelques idées et parler des choses que nous aimons également ! Mais vous avez vraiment choisi l’asile presque inaccessible et je songe avec mélancolie que j’ai failli, voici des années, aller frapper à votre porte à Bournemouth. C’était un peu après vous avoir connu intellectuellement, et un autre démon, celui de la défiance, qui fait qu’on recule devant les rencontres les plus désirées, m’en a empêché. Voilà, Monsieur, beaucoup de diableries dans un petit billet qui devrait être toute chaleur et toute joie puisqu’il me permet de vous prouver ma gratitude d’esprit. Recevez-le comme une poignée de main bien sincère et croyez moi votre vrai et dévoué ami d’esprit.

Paul Bourget

Transcription: Katherine Ashley, Antoine Compagnon and Richard Dury

.

London, 3 August 1893

My dear fellow,

I am so shamefully late in thanking you for the dedication to the fine book at the front of which you put my name, that I’ll never be done asking for forgiveness. The demon of procrastination—that evil genie of all creative people—has played cruel tricks in my life. He will have perpetrated his worst mischief if he has deprived me of the precious sympathy demonstrated by your dedication—and coming from the admirable artist that you are, this sympathy has touched me greatly. Perhaps you’ll find an explanation for my mysterious slowness in an existence that for six long months last year was that of literary labour enslaved by unwise commitment—which is nothing when the work comes // easily, but which is much when one cannot ‘in good conscience do bad work’, as someone whose name escapes me once said.

In thanking you, I’d also like to tell you how much I appreciate your abilities and psychological vision, and how it amuses me, when reading you, to find a singular likeness of temperament between what you express and what I feel on analogous points. Know that, despite my silence, this intellectual fraternity makes of you a distant friend of whom I often think. I’m delighted to learn from Henry James that you have regained your health under the skies where you have taken refuge. How I’d like to hope that we’ll meet one day, and that we’ll be able to exchange ideas in // person and speak of things that we both love equally. But you’ve truly chosen an almost inaccessible sanctuary, and I think with wistfulness that years ago I almost knocked on your door in Bournemouth. It was shortly after getting to know you intellectually, and I was prevented by another demon, the demon of no-confidence that makes us back away from the most desired encounters. That, sir, is a lot of devilry for a short note that ought to be all warmth and pleasure, since it allows me to show my gratefulness. Please accept it as a sincere handshake indeed and consider me your true and devoted like-minded friend.

Paul Bourget

Translation: Katherine Ashley

.

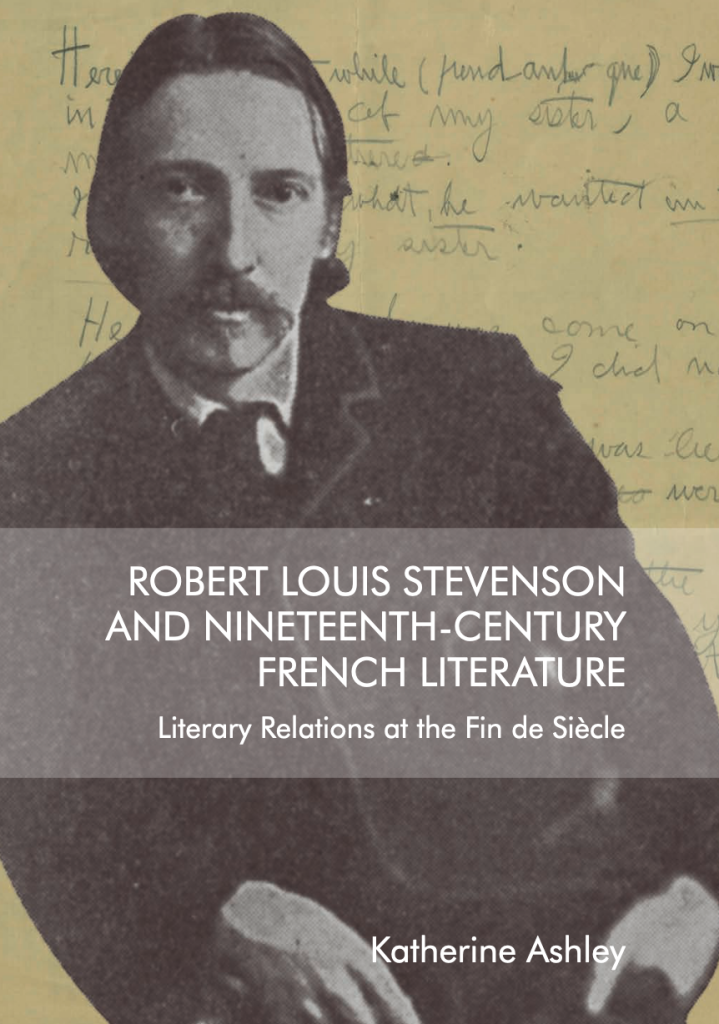

See also the former post on Katherine Ashley’s recent study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stevenson and Dante

A post contributed by Robert-Louis Abrahamson

In his 1878 essay ‘Pan’s Pipes’, Stevenson describes those who ‘hold back the hand from the rose because of the thorn, and from life because of death’ as ‘tooth-chattering ones’. The phrase ‘tooth-chattering’ posed a problem when compiling the notes for my edition of Virginibus Puerisque. Like so many other phrases in the essays, it seemed to be lifted or adapted perhaps from the Bible, or Shakespeare, or some French idiom, but I could find no sources. Richard Dury and I pondered this problem, and the best we could come up with was: ‘an invention of Stevenson’s based on the ancient “kindly ones” (that is, the Eumenides, or Furies)’.

Nearly five years after the edition of Virginibus Puerisque came out, I can supply what I think is a better note. In Canto 3 of Dante’s Inferno, the souls waiting to be transported across the Acheron quake when they hear Charon’s words of doom (‘I come to conduct you nelle tenebre eterne, in caldo e in gelo, into eternal darkness, into fire and ice’). These are the souls who have lost all the goodness life had offered them. Forlorn and naked, changing colour, Dante shows them as they dibattero i denti, they chattered with their teeth. These, of course, are the ‘tooth-chattering ones’. In his essay about one mythic story, Pan, Stevenson draws on another myth, Dante’s journey, and if we catch the infernal allusion, we see these ‘recreant[s] to Pan’ in a much darker light.

RLS2024 ‘Intertextual Stevenson’

Ruhr University Bochum, 27–29 June 2024

Organisers: Lena Linne & Burkhard Niederhoff

In “A College Magazine”, Robert Louis Stevenson famously described his literary apprentice-ship as an exercise in imitation: “I have thus played the sedulous ape to Hazlitt, to Lamb, to Wordsworth, to Sir Thomas Browne, to Defoe, to Hawthorne, to Baudelaire, and to Obermann.” The works that were eventually published are hardly less indebted to previous texts than his earlier attempts at literary pastiche. “No doubt the parrot once belonged to Robinson Crusoe. No doubt the skeleton is conveyed from Poe”, Stevenson admits in “My First Book”, an essay on the genesis and the sources of Treasure Island. Some critics have used these self-depre-cating comments, in particular the “sedulous ape”, to support their claim that Stevenson was a derivative writer lacking in originality. Others, by contrast, have praised him as a precursor of postmodernism who was aware of, and brilliantly exploited, the inevitable intertextuality of all writing.

Many of the papers given at this conference will explore the way Stevenson used, adopted and responded to texts by other writers, and the way other writers used, adopted and responded to texts by him. The term text will be interpreted broadly and papers on film, graphic novels etc. will be welcome.

We also invite comparative papers that engage with analogues or parallels rather than sources and influences, situating Stevenson’s works within a genre or within their nineteenth-century context (e.g. “Stevenson and Wilkie Collins as Writers of Sensation Novels”). Moreover, there is room for theoretical investigations that take their cue from essays such as “A College Magazine” or “My First Book” and analyse Stevenson’s ideas about the genesis and structure of literary texts.

Finally, we will welcome papers that engage with the multiple texts that often lurk behind what is considered a single text; those who are interested in editing Stevenson’s writings could compare different layers or versions of a text and the editorial problems resulting from them. Further creative interpretations of the conference theme are possible and welcome.

Proposals (200-300 words) for twenty-minute papers are warmly invited and should be sent to one of the organisers by November 30, 2023 (lena.linne@rub.de, burkhard.nieder-hoff@rub.de). If you have any questions, please contact the organisers.

RLS and French literature

A post by Katherine Ashley: thoughts on her study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature: Literary Relations at the Fin de Siecle (EUP, 2022)

When we look at how Stevenson interpreted French literary history, how he responded to established and emerging theories of the novel in France, and how he devoured both popular and literary French novels, we can also see how all of these things informed his own writing. From the way that he argues against Naturalism in order to reassert the importance of the romance tradition, to the stylistic apprenticeship that he undertook in earnest and in jest, we see an author developing an approach to literature that went against dominant theories of the Victorian realist novel and challenged conceptions of what “the art of fiction” might entail.

To a new generation of French writers, Stevenson became a beacon of change, presenting a pathway out of the perceived dead end that the French novel had run up against.

Naturalism, with its emphasis on scientific positivism, could only take the novel so far; Decadence, with its emphasis on aestheticism, contained the seeds of its own demise. Stevenson, translated and published in popular and highbrow venues, touted as a bestselling children’s author but also as the figurehead of a cosmopolitan revival, showed that readable page-turners could also be stylistic tours-de-force. This reminded French authors and critics that form and style could themselves be part of the intrigue and the adventure of reading and writing.

This study of reciprocal influence reveals much about the literary debates that rocked late-nineteenth-century Britain and France. To retrace the readings and the relationships – both on an individual level (Stevenson) and on a macro level (Franco-British literature) – required wading through nineteenth-century newspapers, journals, correspondence and novels. This might seem dry, but it was brought to life by the ebullient and boisterous personality at the heart of my research. Stevenson’s voice was a reminder that at the end of the day, literary history is in part the history of individuals who valued the imaginative, creative qualities of language and dedicated their lives to it. For Stevenson, being a man of letters sometimes meant “sedulously aping” literary masters, but it also involved play and fun, spontaneity and pleasure. When researching my book, it was Stevenson’s exuberant multilingual outbursts, his hilarious spoofing of contemporary writers and texts, or the silly French lessons like the one he gave to his stepson Lloyd Osbourne that brought the subject and the subject matter to life.

.

.

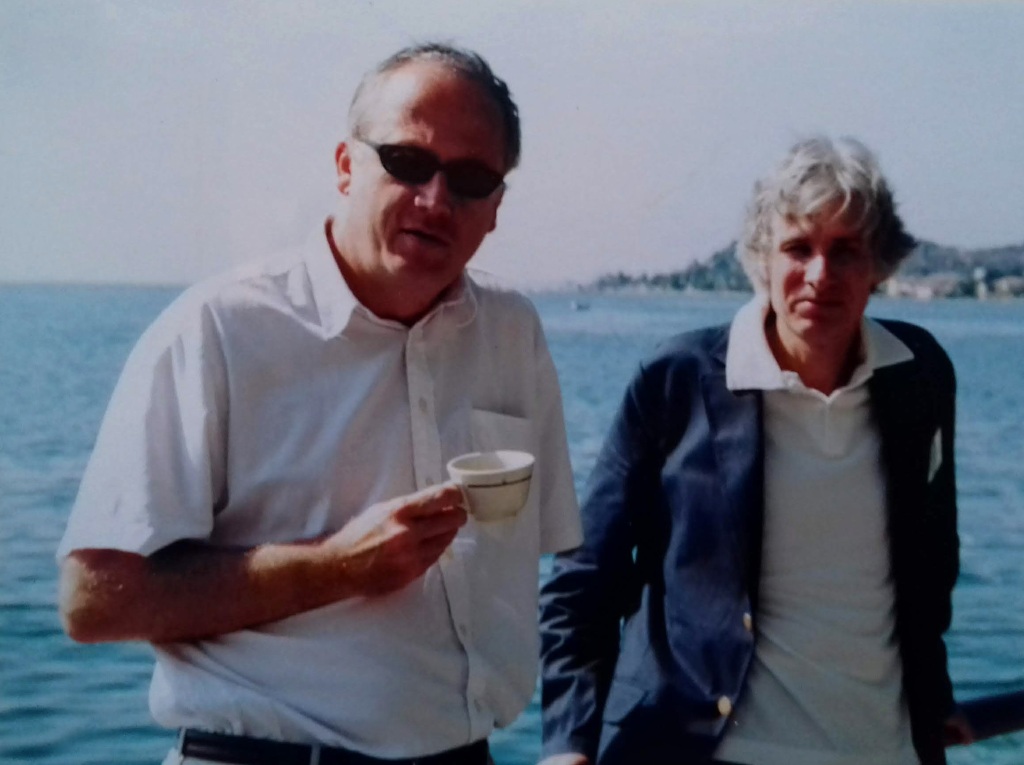

Twenty years ago today: RLS 2002, Gargnano

Twenty years ago today, on Sunday 25 August 2002, the Gargnano Stevenson conference began with registration from 5 to 7 p.m., followed, on the lakeside terrace, by the first aperitivo and and the first cena (pasta all’amatriciana and ‘àrista al forno’—roast pork—con salsa svizzera) in the gathering dusk of the long Gargnano twilight. It was a memorable moment, in a unique location and one of the events that contributed to the revival of academic interest in Stevenson, including the New Edinburgh Edition.

Stevenson, once the most famous and admired writer in English, from about 1918 was gradually excluded for serious consideration by Anglo-American critics. The situation continued for another seventy years: he was dismissed by F. R. Leavis and Raymond Williams and not even mentioned once in The Norton Anthology of English Literature from the first (1962) through to the seventh edition (2000).

Signs of a revival of interest started in the 1980s (with works by Roger Swearingen (1980), Paul Maixner (1981), Barry Menikoff (1984) and the influential collection of essays Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde After One Hundred Years (1988) edited by Veeder & Hirsch). In the same decade Penguin Classics and Oxford Oxford World Classics paperbacks made a number of Stevenson’s works (including the South Seas tales) easily available for the first time in decades.

With the centenary year of 1994 came exhibitions and biographies and the eight volumes of the Yale Letters (edited by B. A. Booth and E. Mehew), closely followed by Alan Sandison’s monograph of 1996, which presented Stevenson not as the tradition to be overcome by Modernism but as its forerunner.

All this activity and interest was further focussed in the milennial year 2000, associated with overviews and assessments in many fields, including the important Stirling Stevenson conference of 2000 (organized by Rory Watson and Eric Massie), which then gave birth to the Journal of Stevenson Studies (which flourished from 2005 to 2018). Stirling was intended as a single conference, but at its closing meeting Richard Ambrosini boldly stood up and proposed a biennial series, to be established by a conference in two year’s time at the Milan University conference centre on Lake Garda.

What a pleasure it was at Stirling and Gargnano to share interests and enthusiasms with a temporary gathering of like-minded others for the very first time. Stirling initiated a focussing of interest and Gargnano and the biennial conferences confirmed it.

.

Below are some photos of the event. If you wish to read my ‘picturesque notes’ on the conference, you will find them here.

Dick Ringler wrote afterwards: ‘That was quite splendid, long-to-be-savored-and-remembered. A total success. And acquiring—in retrospect—something of the quality of a dream.’

Louis, Fanny and ‘Charles of Orleans’

When Stevenson first met Fanny Osbourne and fell in love he accepted an addition she suggested to his latest essay. Her contribution was first noted when preparing the essay for the upcoming New Edinburgh Edition of Stevenson’s Familiar Studies of Men and Books.

On 30 July 1876 Stevenson reported that his essay on ‘Charles of Orleans’ was finished and had been sent off to the Cornhill. The following month he left Edinburgh for London and then Antwerp where he was to begin his Inland Voyage river and canal journey on 25 August. In a letter to Colvin written just before leaving Edinburgh he still hadn’t heard from the Cornhill about the essay (Letters 2: 178, 181).

In the same letter to Colvin he said ‘I have an ultimate purpose of reaching Fontainebleau by water’, but he in fact ended at Pontoise, about about 17 km via the river Oise to the Seine below Paris. On 13 or 14 September he wrote to his mother from Pontoise mentioning ‘a bold, desperado sort of post card from my father; anent a proof of mine; which he has carefully violated as usual’ (Letters 2: 190). This can only refer to the ‘Charles of Orleans’ proofs. The same incident is alluded to at the end of An Inland Voyage, where he says a packet of letters picked up in Compiègne ended the holiday feeling and at their next stop, ‘a letter at Pontoise decided us’, and brought the trip to an end (Tusitala 17: 88, 110).

It is not clear whether it had been agreed that Thomas Stevenson would read the proofs when they arrived, or whether he took it upon himself to open the envelope: certainly, Stevenson did not welcome this interference, and two-and-a-half years later made sure his father did not see the proofs of Travels with a Donkey (Maixner: 64).

*

After Pontoise Stevenson and Simpson continued by rail to Paris and Grez, where they presumably arrived around 16 September—along with the two canoes (Lloyd Osbourne remembers them there). And there at the artist’s inn of Chez Chevillon, Stevenson met his future wife Fanny Osbourne. We have Lloyd Osbourne’s later recollection of Stevenson arriving, vaulting though the open window from the street and being greeted with delight by the company around the dinner table. Louis was attracted to Fanny first; Fanny, we know from her letters, was attracted to Bob Stevenson, but at a certain point he told her that his cousin was more worthy of her attention. (All this un-Victorian fluidity and freedom of relationships must have seemed like a new world to Louis.)

Anyway, they fell in love, ‘step for step, with a fluttered consciousness, like a pair of children venturing together into a dark room’, as Stevenson puts it in ‘Falling in Love’. Lloyd Osbourne remembers how Stevenson and his mother ‘would sit and talk interminably on either side of the dining-room stove while everybody else was out and busy, under vast white umbrellas, in the fields’ (Tusitala 17: xi).

*

One day, Stevenson must have given Fanny those proofs of his latest essay, ‘Charles of Orleans’ to read. The text published in the Cornhill in December of that year contains the following passage:

The reader will remember how Villon’s mother conceived of heaven and hell and took all her scanty stock of theology from the stained glass that threw its light upon her as she prayed. And there is scarcely a detail of external effect in the chronicles and romances of the time, but might have been borrowed at second hand from a piece of tapestry. It was a stage in the history of mankind which we may see paralleled, to some extent, in the first infant school, where the representations of lions and elephants alternate round the wall with moral verses and trite presentments of the lesser virtues. So that to live in a house of many pictures was tantamount, for the time, to a liberal education in itself.

After reading the essay, Fanny suggested the parallel between knowledge conveyed through images in the Middle Ages and the images in the classroom of the infant school, and Stevenson (always interested in parallels between primitive and infant psychology) must have inserted it on the proofs.

We know this because when the essay was collected in Familiar Studies in 1882, Stevenson, replying to a letter from Alexander Japp, said, ‘The elephant was my wife’s: so she is proportionately elate you should have have picked it out for praise’ (Letters 3: 310).