Posts Tagged ‘Paul Bourget’

Paul Bourget writes to Stevenson

A post contributed by Katherine Ashley

In 1891, Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Paul Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (1891). The book gave Stevenson a ‘literal thrill’ and he quickly requested more of his works. Bourget (1852-1935) was a poet, novelist, and playwright, but today he is mainly read by literary historians for his astute study of fin de siècle cultural malaise, Essais de psychologie contemporaine (1885). He was also, like Stevenson, a traveller, and it is fitting that Stevenson’s introduction to him was via Sensations d’Italie, a book about Bourget’s travels in Tuscany, Umbria and Puglia.

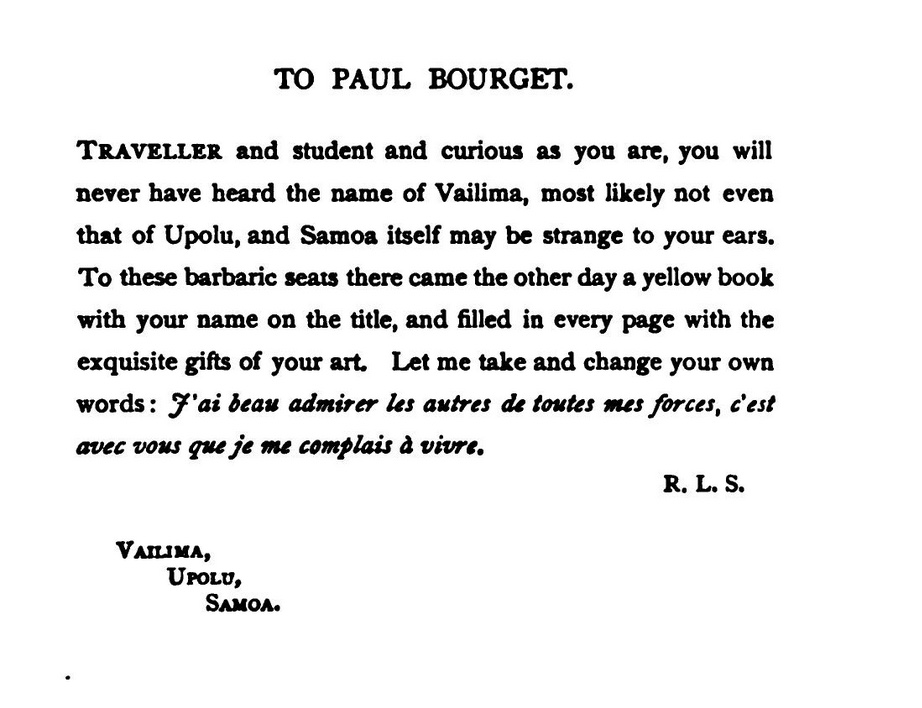

The reasons for Stevenson’s enthusiasm for Sensations d’Italie are explored in an earlier post; a direct result of his reading is that he dedicated Across the Plains (1892) to Bourget.

To Stevenson’s consternation, Bourget did not immediately respond to the compliment. He complained to Sidney Colvin: ‘ain’t it manners in France to acknowledge a dedication? I have never heard a word from le Sieur Bourget, drat his impudence!’. He was even more to the point in a letter to James. Although the tone is good-humoured, there is an element of hurt and annoyance:

I thought Bourget was a friend of yours? And I thought the French were a polite race? He has taken my dedication with a stately silence that has surprised me into apoplexy. Did I go and dedicate my book to the nasty alien, and the ’n’orrid Frenchman, and the Bloody Furrineer? Well, I wouldn’t do it again; and unless his case is susceptible of Explanation, you might perhaps tell him so over the walnuts and the wine, by way of speeding the gay hours. Seriously, I thought my dedication worth a letter.

As it turns out, Bourget’s case was indeed ‘susceptible of Explanation’: work had prevented him from replying. The excuse seems reasonable, since Bourget spent the first months of 1892 in Rome, which resulted in his novel Cosmopolis (1893). He also published two other books around this time, La Terre promise (1892) and Un scrupule (1893).

Bourget’s contrite reply finally came, enclosed in James’s next letter to Stevenson. The manuscript is kept at Harvard University. It is transcribed and translated here.

Londres, le 3 août 93

Monsieur et cher confrère,

Je suis si coupablement en retard avec vous pour vous remercier de la dédicace du beau livre en tête duquel vous avez mis mon nom que je n’en finirais pas de m’en excuser. Le démon de la procrastination—ce mauvais génie de tous les imaginatifs—m’a joué des tours cruels dans ma vie. Il aurait commis le pire de ses méfaits s’il m’avait privé de la précieuse sympathie dont témoignait votre envoi—et venant de l’admirable artiste que vous êtes, cette sympathie m’avait tant touché. Peut-être trouverez-vous le mot de cette énigme de paresse dans une existence qui six mois durant, l’année dernière, a été celle d’un manœuvre littéraire esclavagé par un engagement imprudent—ce qui n’est rien lorsqu’on a le travail // facile, ce qui est beaucoup quand on ne peut pas « faire consciencieusement mauvais » comme disait je ne sais plus qui.

J’aurais voulu aussi, en vous remerciant, vous dire combien j’aime votre faculté et vision psychologique et comme il m’amuse en vous lisant de trouver entre ce que vous exprimez et ce que je sens sur des points analogues de singulières ressemblances d’âme. Croyez que, malgré mon silence, cette fraternité intellectuelle fait de vous un ami éloigné auquel je pense souvent. Je me réjouis de savoir par Henry James que vous avez retrouvé la santé sous le ciel où vous êtes réfugié. Que je voudrais pouvoir espérer qu’un jour nous nous rencontrerons, et que nous pourrons de vive // voix échanger quelques idées et parler des choses que nous aimons également ! Mais vous avez vraiment choisi l’asile presque inaccessible et je songe avec mélancolie que j’ai failli, voici des années, aller frapper à votre porte à Bournemouth. C’était un peu après vous avoir connu intellectuellement, et un autre démon, celui de la défiance, qui fait qu’on recule devant les rencontres les plus désirées, m’en a empêché. Voilà, Monsieur, beaucoup de diableries dans un petit billet qui devrait être toute chaleur et toute joie puisqu’il me permet de vous prouver ma gratitude d’esprit. Recevez-le comme une poignée de main bien sincère et croyez moi votre vrai et dévoué ami d’esprit.

Paul Bourget

Transcription: Katherine Ashley, Antoine Compagnon and Richard Dury

.

London, 3 August 1893

My dear fellow,

I am so shamefully late in thanking you for the dedication to the fine book at the front of which you put my name, that I’ll never be done asking for forgiveness. The demon of procrastination—that evil genie of all creative people—has played cruel tricks in my life. He will have perpetrated his worst mischief if he has deprived me of the precious sympathy demonstrated by your dedication—and coming from the admirable artist that you are, this sympathy has touched me greatly. Perhaps you’ll find an explanation for my mysterious slowness in an existence that for six long months last year was that of literary labour enslaved by unwise commitment—which is nothing when the work comes // easily, but which is much when one cannot ‘in good conscience do bad work’, as someone whose name escapes me once said.

In thanking you, I’d also like to tell you how much I appreciate your abilities and psychological vision, and how it amuses me, when reading you, to find a singular likeness of temperament between what you express and what I feel on analogous points. Know that, despite my silence, this intellectual fraternity makes of you a distant friend of whom I often think. I’m delighted to learn from Henry James that you have regained your health under the skies where you have taken refuge. How I’d like to hope that we’ll meet one day, and that we’ll be able to exchange ideas in // person and speak of things that we both love equally. But you’ve truly chosen an almost inaccessible sanctuary, and I think with wistfulness that years ago I almost knocked on your door in Bournemouth. It was shortly after getting to know you intellectually, and I was prevented by another demon, the demon of no-confidence that makes us back away from the most desired encounters. That, sir, is a lot of devilry for a short note that ought to be all warmth and pleasure, since it allows me to show my gratefulness. Please accept it as a sincere handshake indeed and consider me your true and devoted like-minded friend.

Paul Bourget

Translation: Katherine Ashley

.

See also the former post on Katherine Ashley’s recent study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stevenson and Bourget: an enigma

Why was RLS so enthusiastic about Sensations d’Italie?

Paul Bourget (1852–1935), French critic, essayist, novelist and poet, much appreciated in his own day, is not now widely known even in France. The publisher’s presentation of an introductory volume Avez-vous lu Paul Bourget? (2007) begins by saying that he is now ‘little known, even scorned’ (‘méconnu, voire méprisé’). Quite a downfall for a writer who was nominated for the Nobel prize no fewer than four times.

Stevenson’s reaction to Sensations d’Italie

Bourget’s friend Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Sensations d’Italie (1891), which he later described to Stevenson as ‘one of the most exquisite things of our time’ (Letters of Henry James, I, p. 188). Stevenson was enthusiastic—sent off immediately for all Bourget’s essays and at the same time wrote ‘I have gone crazy over Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (L7, 197, 205) and told James ‘I am delighted beyond expression by Bourget’s book; he has phrases which effect me almost like Montaigne’ and the following day told him, ‘I have just been breakfasting at Baiae and Brindisi, and this charm of Bourget hag-rides me. […] I have read no new book for years that gave me the same literary thrill as his Sensations d’Italie‘ (L7, 210–11) Not only this, but he looked forward to meeting Bourget on a planned trip to Europe and dedicated Across the Plains to him, the only one of his volumes not dedicated to a personal friend or family member.

You cannot step twice into the same book

Some years ago, inspired by such an impressive recommendation, I bought a second-hand copy of Sensations d’Italie, expecting it to be a cross between Montaigne and Proust and promising myself an exquisite reading experience. Unfortunately, what struck me then were the mentions of trains and inns and long appreciations of paintings. It did not resemble Stevenson’s own travel writing: there are no descriptions of his feelings or of the people he meets, no detached irony.

Why was Stevenson so enthusiastic? The best way to answer this question would be to look at his copy of the book with his scorings and approving underlinings. It is in the Fales Library of New York University on Washington Square in Manhattan—which unfortunately is closed because of the present pandemic emergency, and probably will be closed after that as closure for renovation was planned from May to September 2020.

Stevenson’s copy being unavailable, I decided to re-read the copy I had with a fresh eye, suppressing the expectations of the previous occasion.

Amazingly, this time I read a different book. I noticed the essayistic passages about art and artistry, the ethical, psychological and aesthetic passages and the embedded narratives with striking and memorable details. The uncomfortable trains and inns were still there, but this time they faded into the background.

What Stevenson may have appreciated

We cannot be certain about what Stevenson liked about Sensations d’Italie but we can make an educated guess, especially concerning aspects that might have found an echo in his own thinking. When Stevenson’s copy of Sensations d’Italie becomes available again, it will be interesting to see which of the following passages are marked. (Quotations are from the 1892 English translation, Impressions of Italy, with page references followed by page references of Sensations d’Italie.)

[March 2024: Stevenson’s copy has now been consulted (the results can be found here) and the following ‘educated guesses’ annotated according to the markings found there.

.

1. Affiinities with Montaigne

One clue from Stevenson’s letters on the book is his praise for ‘phrases which effect me almost like Montaigne’. I think perhaps he may be thinking here of Montaigne’s striking metaphors (such as that of the give and take of conversation being like playing tennis). Here is what seems a Montaigne-like metaphor:

1.1 In every work of art, whether it be a picture or a book, a statue or a piece of music, there is a hidden principle of life, that is to say, a secret virtuality unsuspected by the creator of the work. Have you ever seen a ropemaker at his work, walking backward without looking where he is going ? We are all, great and small, working like him, half consciously, half blindly, and above all we do not know what purpose our work will serve when it is finished. (126; SdI, 129–30)

[marked]

2. Affinities with Stevenson’s style:

2.1 Chapter 17 begins realistically with the ‘local train which moves almost like a steam tramway’ across ‘the vast plain of Apulia’ but then it changes register to the imaginative picturesque as Bourget’s destination reminds him of the story of how Manfred, last of the Hohenstaufen dynasty of Sicily, following defeat by Charles of Anjou and the revolt of his barons, sought refuge in Lucera ‘among his father’s Saracens’.

The story, too long to quote in full here, reminds me of Stevenson’s praise of ‘the poetry of circumstance’, ‘the fitness in events and places’, and ‘fit and striking incident’, ‘which stamps the story home like an illustration’ (in ‘A Gossip on Romance’). It has elements that are similar to the assassination of Archbishop Sharp that had long fascinated Stevenson and that he recounts in ‘The History of Fife’. In short, I hereby predict that when the volume in the Fales Library can be consulted again, the pages containing the story of Manfred’s flight (SdI, 179–82) will be approvingly marked in Stevenson’s hand.

Bourget says that the story is recorded by a chronicler ‘with a rare mixture of strength and simplicity’ (reminding me of Stevenson’s attraction to the prose of the Covenanters), it is a kind of passage that is ‘short, but which remain in the memory’ (‘si courtes mais qui restent dans l’esprit‘), like the ‘striking incident’ praised by Stevenson in ‘A Gossip on Romance’. Bourget then quotes the words of the chronicler:

He accordingly set out on a November night, accompanied by a scanty escort, to ride across this plain of Tavoliere to an asylum of which he was not even sure. The rain was falling. ‘It augmented,’ says Jamsilla, ‘the darkness of the night. The prince and his companions were unable to see one another. They could recognize each other only by the sound of the voice and by the touch. They did not even know whither the road they were following led, for they had ridden across the open country in order to throw possible pursuers off the scent.’ (175; SdI, 180–1)

After a bivouac overnight Manfred arrived at the walls of Lucera where ‘he was obliged to make himself known — an incident so romantic as to seem taken from a romance [trait si romanesque qu’il en semble romantique] — by his beautiful fair hair.’ The Moors had orders not to admit him, but said he could get round the order by entering through the sewer. Manfred prepared to do this and then (in the words of the chronicler) ‘This humiliation of the son of their beloved emperor awakened their remorse. They broke down the gates and Manfred entered in triumph.’

[this whole episode is marked]

2.2 The only clue from his letters as to what part of Bourget’s book he might have found fascinating is the comment, ‘I have just been breakfasting at Baiae and Brindisi, and this charm of Bourget hag-rides me’. It should be mentioned, however, that Bourget does not go near Baiae or Naples, so Stevenson has just introduced that name for the alliteration to suggest a large part of southern Italy. Brindisi, however, is there and is associated with a haunting impression:

by having heard, by hearing still, the clanking of the chains worn by the galley-slaves resounding through the castle on the seashore. I have seen many prisons and many abodes of misery, […], but nothing has pierced my heart like the sound of those chains, forever and forever accompanying my steps, as I walked through the courts and the halls of the fortress. […] The noise made by each one, walking with his heavy step, is slight ; but all these slight sounds of iron clanking against iron unite together in a sort of metallic roar, making the whole fortress vibrate. It is indistinct, mysterious, sinister’ (217–18; SdI, 222–3)

[not marked, though he does mark a vignette of contrasting misery and affection from the same prison (SdI, 224.6–13]

This reminds me of the haunting sound of the waves in Treasure Island and in other texts by Stevenson.

2.3 Perhaps too Stevenson appreciated impressionistic descriptions that reminded him of his writing in the 1870s, such as:

Little girls […] whisper and laugh together and shake their pretty heads, bright patches on the dark background of the church [taches clairs sur le fond obscur de l’église]. (74; SdI, 75)

[not marked]

.

3. Ethical concerns

3.1 Stevenson admired those who did what they thought was right and bravely faced the consequences, like the Covenanters and Yoshida-Torajiri, with his ‘stubborn superiority to defeat’, and Bourget provides us with another example of such a type. In ch. 21 he visits the castle of duke Sigismondo Castromediano: a ‘deserted manor’ where everything shows ‘a strange abandonment’, yet inhabited by the eighty-year old Duke who

has suffered all the tortures of a proscription as cruel as that of the companions of the Stuart conspirator. He threw himself, heart and soul, into the movement against the Bourbons of Naples, after the events of 1848. Arrested and condemned to death, his sentence was commuted to imprisonment for life in the galleys, and, refusing to sue for pardon, he was for eleven years a galley-slave. (241; SdI, 246)

Eventually he escaped to England and returned at the time of Garibaldi. The castle ‘he has left untouched whether from a stoical indifference in regard to the comforts of life, acquired in misfortune, or from pride in his sufferings’ (242; SdI, 247).

[not marked]

.

4. Psychological concerns

4.1 From about 1880 Stevenson was increasingly interested in how we can understand the world-view of people from very different cultural traditions, and we find this too in Bourget:

[the myths of the ancients:] the human feeling which underlies their religious ideal makes it possible for us to have communion with them, in spite of the differences of creeds and customs. (92; SdI, 95)

[not marked, but see the related next item]

4.2 In two essays written in 1887 ‘Pastoral’ and ‘The Manse’, Stevenson speculates on inherited primitive memories and how his ancestors are a part of him and he found some similar thoughts in Bourget:

the innumerable threads which heredity inextricably weaves into our being, so that in the sincere Christians of to-day their pagan ancestors, and other ancestors of still darker beliefs, live again (273; SdI, 279).

[not marked, but a related idea about pagan survivals is (SdI, 196.18–197.8)]

4.3 The following passage has various echoes in Stevenson’s idea of constant variation in identity;

[T]he varying complexity of the I [la complexité changeante du moi] (56–7; SdI, 58)

[not marked]

4.4 In Bourget, Stevenson would have found ideas that were close to his own about the moral nature of the artist, about ‘the sympathetic interpretation of feeling’, and about the hidden feelings and motives that he explores in ‘The Lantern Bearers’:

talent has always, and without exception, a close resemblance to the moral nature of the individual. I mean a certain sort of talent; that which consists neither in facility of execution, nor a profound knowledge of effects, but in a sympathetic interpretation of feeling. The facts of a man’s life are so little significant of his real nature! The likeness of us which our actions stamp on the imagination of others is so deceptive! Do others, even, ever thoroughly understand our actions, and if they understand them are they able to unravel their hidden motives? Do we confide to others the world of thoughts that has stirred within us since we have come into existence: our inmost feelings, the secret tragedy of our hopes and our sorrows, the pangs of wounded self-love, the disappointment of ideals overthrown? (45; SdI, 46)

[marked, and the sentence on ‘The facts of a man’s life’ is underlined]

4.5 Neither the doctrines of these believers nor their prejudices concern us any longer; it is their I — like ours in its secret needs, but which possessed what we so greatly desire — yes, it is this pious and heroic I which kindles our fervor from the depths of the impenetrable abyss into which it has returned. (140; SdI, 143–4)

[not marked]

5. Thoughts on art and aesthetics

Finally, Stevenson was interested not only in theories of narrative and in technique and style but also in the philosophy of art, the nature of artistic genius, common elements of all the arts, the relationship between the artist and the finished work, the elusive charm of the artistic experience. Bourget too was interested in these aesthetic questions and in his book Stevenson would have found a writer with whom he could engage in an exchange of ideas.

5.1 ‘Why, recognizing in every human action something of unconsciousness and of destiny, should we not admit that the genius of the great artists was greater than they themselves knew?’ (53; SdI, 53)

[not marked, but a similar idea is marked (Sens, pp. 129.12–132.4)]

5.2 Is the purpose of literature, then — I mean literature which is worthy of the name — different from that of the other arts — music and architecture, sculpture and painting ? Like them, and in a language of its own, what does it express but shades of human feeling? (130; SdI, 133–4)

[marked]

5.3 The supreme gift reveals itself in them [artists of genius], as it does wherever it is met with, by the master virtue, unerring clearness of vision. (137; SdI, 140–1)

[not marked]

5.4 This word [charm], so vague in its signification, […] is the only one which expresses the magic of certain […] works, shadowy, incomplete, […] but by which one feels one’s self loved as by a person, and which one loves in the same way. There are two classes of artists who have always shared between them the dominion of the world: those who depict objects, effacing themselves altogether ; and those whose works serve chiefly as a pretext to lay bare their own hearts. It is in vain that I admire the former with my whole strength and tell myself that they will never deceive me, while the sincerity of the others is often doubtful and they may always be suspected of posing — my sympathies go with the latter, it is with them I like to be. (117–18; SdI, 120–1)

[marked; the final passage beginning ‘There are two classes of artist’ has a double marginal line]

5.5 a book […] is not entirely the same a hundred years after it has been written. The words are unchanged, but do they preserve exactly the same signification ? What reader of intellectual tastes does not understand that for a man of the seventeenth century Racine’s poetry was not what it has become for us ? (127; SdI, 130)

[marked]