Archive for July 2022

Louis, Fanny and ‘Charles of Orleans’

When Stevenson first met Fanny Osbourne and fell in love he accepted an addition she suggested to his latest essay. Her contribution was first noted when preparing the essay for the upcoming New Edinburgh Edition of Stevenson’s Familiar Studies of Men and Books.

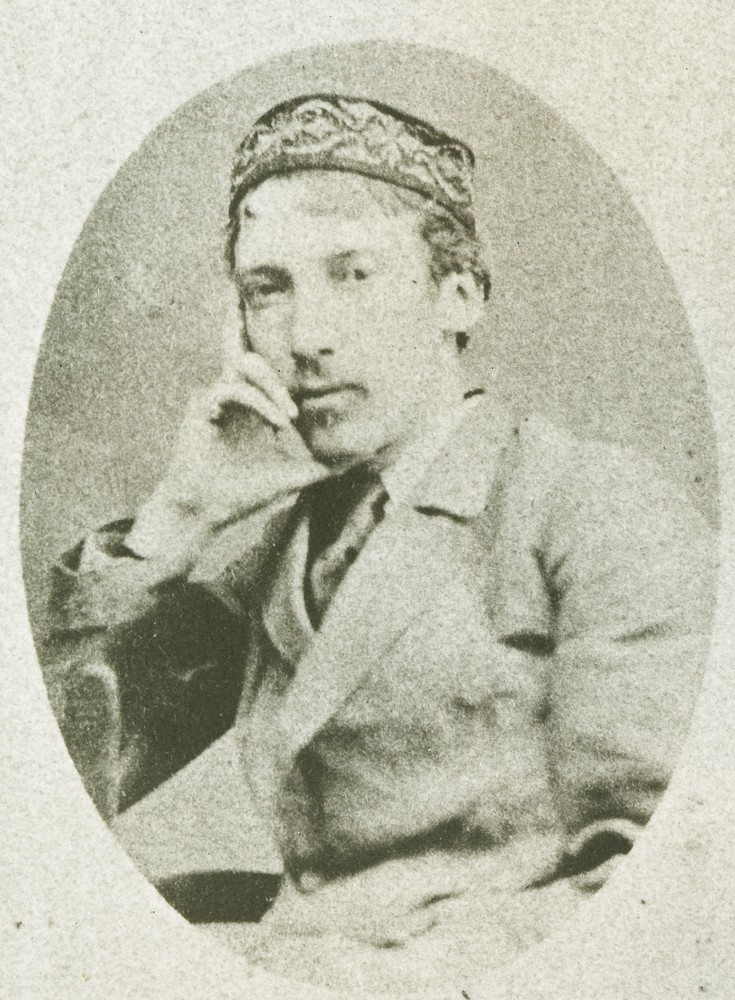

On 30 July 1876 Stevenson reported that his essay on ‘Charles of Orleans’ was finished and had been sent off to the Cornhill. The following month he left Edinburgh for London and then Antwerp where he was to begin his Inland Voyage river and canal journey on 25 August. In a letter to Colvin written just before leaving Edinburgh he still hadn’t heard from the Cornhill about the essay (Letters 2: 178, 181).

In the same letter to Colvin he said ‘I have an ultimate purpose of reaching Fontainebleau by water’, but he in fact ended at Pontoise, about about 17 km via the river Oise to the Seine below Paris. On 13 or 14 September he wrote to his mother from Pontoise mentioning ‘a bold, desperado sort of post card from my father; anent a proof of mine; which he has carefully violated as usual’ (Letters 2: 190). This can only refer to the ‘Charles of Orleans’ proofs. The same incident is alluded to at the end of An Inland Voyage, where he says a packet of letters picked up in Compiègne ended the holiday feeling and at their next stop, ‘a letter at Pontoise decided us’, and brought the trip to an end (Tusitala 17: 88, 110).

It is not clear whether it had been agreed that Thomas Stevenson would read the proofs when they arrived, or whether he took it upon himself to open the envelope: certainly, Stevenson did not welcome this interference, and two-and-a-half years later made sure his father did not see the proofs of Travels with a Donkey (Maixner: 64).

*

After Pontoise Stevenson and Simpson continued by rail to Paris and Grez, where they presumably arrived around 16 September—along with the two canoes (Lloyd Osbourne remembers them there). And there at the artist’s inn of Chez Chevillon, Stevenson met his future wife Fanny Osbourne. We have Lloyd Osbourne’s later recollection of Stevenson arriving, vaulting though the open window from the street and being greeted with delight by the company around the dinner table. Louis was attracted to Fanny first; Fanny, we know from her letters, was attracted to Bob Stevenson, but at a certain point he told her that his cousin was more worthy of her attention. (All this un-Victorian fluidity and freedom of relationships must have seemed like a new world to Louis.)

Anyway, they fell in love, ‘step for step, with a fluttered consciousness, like a pair of children venturing together into a dark room’, as Stevenson puts it in ‘Falling in Love’. Lloyd Osbourne remembers how Stevenson and his mother ‘would sit and talk interminably on either side of the dining-room stove while everybody else was out and busy, under vast white umbrellas, in the fields’ (Tusitala 17: xi).

*

One day, Stevenson must have given Fanny those proofs of his latest essay, ‘Charles of Orleans’ to read. The text published in the Cornhill in December of that year contains the following passage:

The reader will remember how Villon’s mother conceived of heaven and hell and took all her scanty stock of theology from the stained glass that threw its light upon her as she prayed. And there is scarcely a detail of external effect in the chronicles and romances of the time, but might have been borrowed at second hand from a piece of tapestry. It was a stage in the history of mankind which we may see paralleled, to some extent, in the first infant school, where the representations of lions and elephants alternate round the wall with moral verses and trite presentments of the lesser virtues. So that to live in a house of many pictures was tantamount, for the time, to a liberal education in itself.

After reading the essay, Fanny suggested the parallel between knowledge conveyed through images in the Middle Ages and the images in the classroom of the infant school, and Stevenson (always interested in parallels between primitive and infant psychology) must have inserted it on the proofs.

We know this because when the essay was collected in Familiar Studies in 1882, Stevenson, replying to a letter from Alexander Japp, said, ‘The elephant was my wife’s: so she is proportionately elate you should have have picked it out for praise’ (Letters 3: 310).

Stevenson and Pacific Christianity

A post contributed by L. M. Ratnapalan

author of Robert Louis Stevenson and the Pacific: The Transformation of Global Christianity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, March 2023)

Studying Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pacific writings and their contribution to anthropology, I was struck by their many references to religion: local beliefs and practices, churches, nuns, pastors, and converts. The published studies of Stevenson that I read focussed almost entirely on his view of Western missionaries. The consensus was: he was a critical friend of missionaries considering them to be ‘by far the best and the most useful whites in the Pacific’, but that he found their attempts to change Polynesian habits led to consequences that were ‘bloodier than a bombardment’.(1) These studies, however, typically paid little attention to the wider world of Pacific Christianity. Above all, the indigenous Christians Stevenson wrote so much about were hardly discussed at all.

I believe that the reasons for this are at least partly cultural. Growing up in Britain, I had come to think of Christianity as a personal belief, held by a diminishing number of people, who mainly practiced it in private. But when I moved to South Korea in 2012 I was struck by the centrality of Christianity, its practices and discourses, even in a modern city like Seoul: bright crosses light up the night sky; people pray with a rosary in the park; Church attendance is important; and the most popular evening talk show featured a famous pastor as a weekly contributor.

While living in Britain, I had gained the impression that organized religion was everywhere in decline and that secularization was the dominant force; now I could see that the bigger story was not the shrinking of religious affiliation but rather the explosive growth of Christianity (and Islam). The religious picture of the world was undergoing transformation and the key agents were indigenous Christians from Africa, Asia, South America, and the Island Pacific.(2) The vast majority of the world’s Christians now live outside Europe.(3)

In most Pacific Islands comfortably 95 per cent of the population describe themselves as Christian.(3) With this understanding, I felt that I was in a better position to analyze Stevenson’s South Seas writing. A well-known image of the author and his family in Samoa will help to explain what I mean.

Seated and standing around the Stevensons, Osbournes, and their maid are Pacific Islanders, but who were they? The household retinue was composed not only of Samoans but also of Islanders from many other parts of the Pacific. For example, while the cook Talolo (seated directly in front of RLS) was Samoan, Savea (seated far left), who worked on the plantation, was probably a Wallis Islander, and Arrick (seated in front of Talolo) was from the New Hebrides. Yet though they originated from widely separated communities, they were united in a common Christian culture. The workers on the Stevenson estate reflected a mobile Pacific world in which Christianity was common currency, a situation also reflected in Stevenson’s writings, featuring the Pacific-wide movement of Islanders and religious talk.

My project developed to become a study of the impact of Pacific Islands Christianity on Robert Louis Stevenson. I argue that ‘the Beach of Falesá’ could be seen as a meditation on the social effects of missionaries in the Islands.(5) His Pacific fiction deserves reassessment, I thought, in the light of his fascination with the difference between Islanders’ adoption of Christianity as an outward façade (‘indigenization’) and a deeper cultural and spiritual engagement with it (‘inculturation’).(6) The quickness with which he was able to absorb what he experienced was remarkable. During the period 1888–94, as he moved from Pacific traveller to Samoan resident, he progressed from a somewhat sceptical assessment of the efficacy of local religious conversions to a view that mixed the personal with the political. (7) In a forthcoming book, I explore how his Scottish Presbyterian upbringing guided Stevenson’s understanding of Pacific culture, and how Pacific Islanders in turn helped to change the way that he thought about Christianity.(8)

A personal shift of viewpoint has produced these conclusions. Stevenson once wrote that ‘There is no foreign land; it is the traveller only that is foreign’.(9) In the Pacific, he found that ideas such as Christianity could also cover great distances to become foreign to the traveller, and so light up ‘the contrasts of the earth’.

L. M. Ratnapalan, Yonsei University

(1) Robert Louis Stevenson, In the South Seas (London: Penguin, 1998), 64, 34.

(2) Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith

(New York: Orbis, 1996); Jehu J. Hanciles, Migration and the Making of Global Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2021).

(3) Pew Research Center, ‘Global Christianity – A Report on the size and distribution of the World’s Christian population’ (2011): https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2011/12/19/global-christianity-exec/

(4) Kenneth R. Ross, Katalina Tahaafe-Williams, and Todd M. Johnson, eds. Christianity in Oceania

(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

(5) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘Missionary Christianity and Culture in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Beach of Falesá”’, Religion and Literature, 53.3 (2021).

(6) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘Half Christian: Indigenization and Inculturation in Stevenson’s Pacific Fiction’, Scottish Literary Review 12, 1 (2020).

(7) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘“Our Father’s Footprints”: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Anthropology of Conversion, 1888-1894’, Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, 11.1 (forthcoming).

(8) L. M. Ratnapalan, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Pacific: The Transformation of Global Christianity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, scheduled March 2023).

(9) Robert Louis Stevenson, The Silverado Squatters (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884), 113-4.

Images

Vailima family: https://www.thenational.scot/news/17887450.story-samoas-love-robert-louis-stevenson/

Upcoming volume: https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-robert-louis-stevenson-and-the-pacific.html

RLS and Graham Greene

A first cousin of Robert Louis Stevenson on his mother’s side, Jane Whytt (1846–1903), was the maternal grandmother of the novelist Graham Greene (1904–1991). He was very conscious of the family connection and in an interview said that he reacted against the writing of Virginia Woolf ‘by being a storyteller. You see, my mother was a cousin to Robert Louis Stevenson and I’d like to think I’ve followed in his tradition’.(1) Leslie A. Fiedler links Greene with Stevenson, Melville and Doyle as writers who begin with ‘the Romance of the incident, the boys’ story or the thriller’, and move towards ‘evocation of myth’.(2)

In 1947 he started work on a biography of Stevenson but abandoned it because J. C. Furnas was working on a substantial biography and reassessment (Voyage to Windward, 1951); his notes for the project are now in the John J. Burns library of Boston College, and his views on Stevenson can be garnered from his Collected Essays.(4)

Re-reading The Third Man

When recently re-reading Graham Greene’s novella The Third Man (1950), written to provide a screenplay for the 1949 film directed by Carol Reed, I was struck by certain elements that reminded me of Robert Louis Stevenson. Apart from the plot bordering on popular genres (of thriller, spy and detective story); the memorable linking of setting and incident; the ambiguity of characters and uncertainty of interpretation of events, there were other elements that stood out as reminiscent.

Prose style. The prose style is different, of course, but what about Greene’s ‘the thin patient snow’ and ‘curious free unformed laughter’ (chs. 2, 8; pp. 21, 56).(3) These seemed like unexpected Stevensonian epithets (such as ‘the deliberate seasons’, ‘the outrageous breakers’).

Duality. Then there was the element of elusive duality in human personality reflected in first and family name: ‘There was always a conflict in Rollo Martins—between the absurd Christian name and the sturdy Dutch […] surname. Rollo looked at every woman that passed, and Martins renounced them for ever’ (ch. 2; p. 18). And later when Martins hesitates to tell the waiting policeman that Harry Lime was escaping from the café where he had been lured by the detective Calloway, it is explained as follows: ‘I suppose it was not Lime, the penicillin racketeer, who was escaping down the street; it was Harry’ (ch. 16; p. 113).

This alignment of personal and public name with behaviour that is instinctive and controlled, or with the personalities that are private and public reminds me of Weir of Hermiston, when Frank Innes says of Archie Weir, ‘I know Weir; but I never met Archie’ (ch. 2), as well as the idea of divided, non-unitary personality in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and elsewhere in Stevenson. Martins, like Jekyll, feels this interior struggle: ‘It needed all Martin’s resolution to stop Rollo saying […]’ (ch. 3; p. 31).

Charming villain. Perhaps Harry Lime (in Greene’s novella and in the interpretation by Orson Welles in the film) owes something to Stevenson’s characters who combine charm and a-morality (Long John Silver and James Durie).

The famous final scene in the film. There was one other thing that rang a Stevensonian bell for me, this time not from Stevenson’s writings but from writings about his life. When Calloway and Martins drive away from the first (fictitious) burial of Lime at the beginning of the story, Calloway notices that Martins does not look back, though he has just taken part in the burial of his friend:

I noticed that Martins never looked behind — it’s nearly always the fake mourners and the fake lovers who take that last look, who wait waving on platforms, instead of clearing quickly out, not looking back. (ch. 2; p. 22)

That note about platforms and ‘not looking back’ reminded me of one of Lloyd Osbourne’s most memorable pieces of writing, which Greene must have known: the final sentences in an essay describing Osbourne and his mother parting from Stevenson at Euston station to return to California in 1878:

I had no idea of the quandary my mother and R. L. S. were in […] I prattled endlessly about ‘going home’, and enjoyed our preparations, while to them that imminent August spelled the knell of everything that made life worth living. But when the time came I had my own tragedy of parting, and the picture lives with me today as clearly as though it were yesterday. We were standing in front of our compartment, and the moment to say good-bye had come. It was terribly short and sudden and final, and before I could almost realize it R. L. S. was walking away down the platform, a diminishing figure in a brown ulster. My eyes followed him hoping that he would look back. But he never turned, and finally disappeared in the crowd. Words cannot express the sense of bereavement, of desolation that suddenly struck at my heart. I knew I would never see him again. (‘Stevenson at Twenty-Eight’; Tusitala Edition, vol. 25, p. x)

This reminds me of the famous last scene in the film, a full minute of one shot: Martins leaning against a wagon in the left foreground as Anna ‘approaches from a great distance, getting progressively closer, and — without so much as a glance in his direction — finally walking past him and out of frame’ (Richard Raskin).

It’s different from the passages from Greene and Osbourne given above (walking away vs walking towards; not looking back vs not looking to one side etc.), but there is an affinity and equivalence in walking down the long platform and walking down the long avenue, in the deep feelings of bereavement preventing any conventional interaction, and in the inexorable marking of an end.

In Greene’s screenplay Rollo and Anna actually decide to drive off together and it was the director Carol Reed who insisted on this striking end (Anna unforgiving, still held by her fatal love for Lime), but it could have been suggested by Greene’s comment about ‘not looking back’.

That makes two levels of supposition: Stevenson at Euston station possibly linked to Greene’s passage about ‘not looking back’ when saying goodbye at a station platform, and this possibly linked to Carol Reed’s choice for the final scene in the film. Mmm, two imagined links could be used to connect almost anything, so let’s forget that possibility. But, just for our own amusement, let’s imagine a long one-minute single shot to conclude an imaginary film: Stevenson turning and walking, walking along the platform till he becomes very small and is lost in the crowd. Add a suitable film score. At the end, steam, released from among the wheels, gradually fills the screen.

- John R. McArthur, Graham Greene: The Last Interview (Brooklyn/London: Melville House, 2019), p. 112.

- ‘R.L.S. Revisited’, No! in Thunder (1960), qu. in Harold Bloom (ed.), Bloom’s Modern Critical Views: Robert Louis Stevenson (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2005), p. 14.

- Penguin edition, 1971 and reprints.

- edited by John Maynard, 1969 (available on archive.org).