Archive for the ‘Manuscript transcription’ Category

Paul Bourget writes to Stevenson

A post contributed by Katherine Ashley

In 1891, Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Paul Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (1891). The book gave Stevenson a ‘literal thrill’ and he quickly requested more of his works. Bourget (1852-1935) was a poet, novelist, and playwright, but today he is mainly read by literary historians for his astute study of fin de siècle cultural malaise, Essais de psychologie contemporaine (1885). He was also, like Stevenson, a traveller, and it is fitting that Stevenson’s introduction to him was via Sensations d’Italie, a book about Bourget’s travels in Tuscany, Umbria and Puglia.

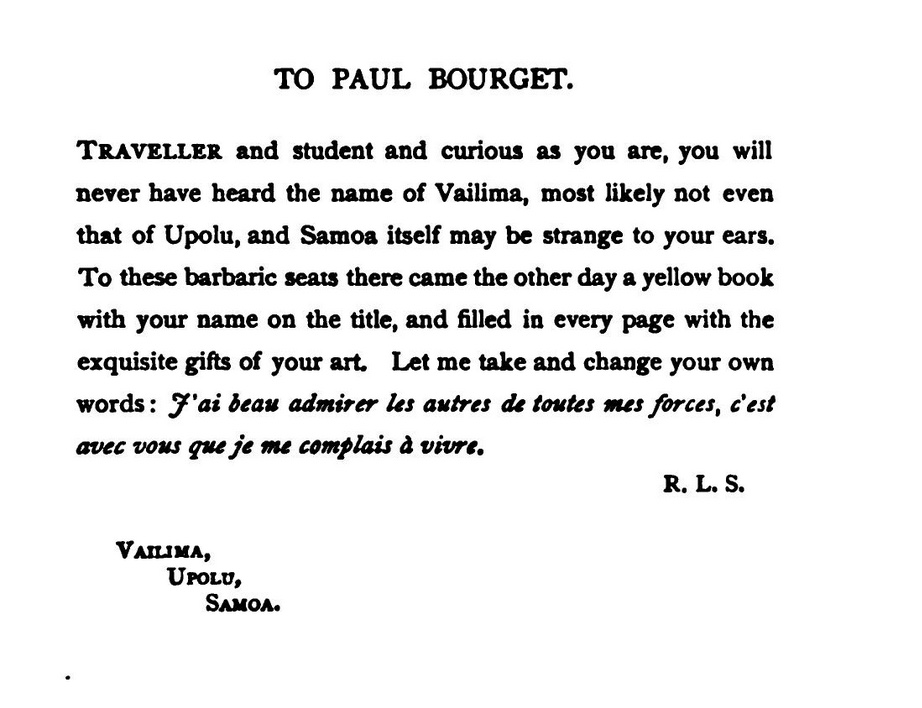

The reasons for Stevenson’s enthusiasm for Sensations d’Italie are explored in an earlier post; a direct result of his reading is that he dedicated Across the Plains (1892) to Bourget.

To Stevenson’s consternation, Bourget did not immediately respond to the compliment. He complained to Sidney Colvin: ‘ain’t it manners in France to acknowledge a dedication? I have never heard a word from le Sieur Bourget, drat his impudence!’. He was even more to the point in a letter to James. Although the tone is good-humoured, there is an element of hurt and annoyance:

I thought Bourget was a friend of yours? And I thought the French were a polite race? He has taken my dedication with a stately silence that has surprised me into apoplexy. Did I go and dedicate my book to the nasty alien, and the ’n’orrid Frenchman, and the Bloody Furrineer? Well, I wouldn’t do it again; and unless his case is susceptible of Explanation, you might perhaps tell him so over the walnuts and the wine, by way of speeding the gay hours. Seriously, I thought my dedication worth a letter.

As it turns out, Bourget’s case was indeed ‘susceptible of Explanation’: work had prevented him from replying. The excuse seems reasonable, since Bourget spent the first months of 1892 in Rome, which resulted in his novel Cosmopolis (1893). He also published two other books around this time, La Terre promise (1892) and Un scrupule (1893).

Bourget’s contrite reply finally came, enclosed in James’s next letter to Stevenson. The manuscript is kept at Harvard University. It is transcribed and translated here.

Londres, le 3 août 93

Monsieur et cher confrère,

Je suis si coupablement en retard avec vous pour vous remercier de la dédicace du beau livre en tête duquel vous avez mis mon nom que je n’en finirais pas de m’en excuser. Le démon de la procrastination—ce mauvais génie de tous les imaginatifs—m’a joué des tours cruels dans ma vie. Il aurait commis le pire de ses méfaits s’il m’avait privé de la précieuse sympathie dont témoignait votre envoi—et venant de l’admirable artiste que vous êtes, cette sympathie m’avait tant touché. Peut-être trouverez-vous le mot de cette énigme de paresse dans une existence qui six mois durant, l’année dernière, a été celle d’un manœuvre littéraire esclavagé par un engagement imprudent—ce qui n’est rien lorsqu’on a le travail // facile, ce qui est beaucoup quand on ne peut pas « faire consciencieusement mauvais » comme disait je ne sais plus qui.

J’aurais voulu aussi, en vous remerciant, vous dire combien j’aime votre faculté et vision psychologique et comme il m’amuse en vous lisant de trouver entre ce que vous exprimez et ce que je sens sur des points analogues de singulières ressemblances d’âme. Croyez que, malgré mon silence, cette fraternité intellectuelle fait de vous un ami éloigné auquel je pense souvent. Je me réjouis de savoir par Henry James que vous avez retrouvé la santé sous le ciel où vous êtes réfugié. Que je voudrais pouvoir espérer qu’un jour nous nous rencontrerons, et que nous pourrons de vive // voix échanger quelques idées et parler des choses que nous aimons également ! Mais vous avez vraiment choisi l’asile presque inaccessible et je songe avec mélancolie que j’ai failli, voici des années, aller frapper à votre porte à Bournemouth. C’était un peu après vous avoir connu intellectuellement, et un autre démon, celui de la défiance, qui fait qu’on recule devant les rencontres les plus désirées, m’en a empêché. Voilà, Monsieur, beaucoup de diableries dans un petit billet qui devrait être toute chaleur et toute joie puisqu’il me permet de vous prouver ma gratitude d’esprit. Recevez-le comme une poignée de main bien sincère et croyez moi votre vrai et dévoué ami d’esprit.

Paul Bourget

Transcription: Katherine Ashley, Antoine Compagnon and Richard Dury

.

London, 3 August 1893

My dear fellow,

I am so shamefully late in thanking you for the dedication to the fine book at the front of which you put my name, that I’ll never be done asking for forgiveness. The demon of procrastination—that evil genie of all creative people—has played cruel tricks in my life. He will have perpetrated his worst mischief if he has deprived me of the precious sympathy demonstrated by your dedication—and coming from the admirable artist that you are, this sympathy has touched me greatly. Perhaps you’ll find an explanation for my mysterious slowness in an existence that for six long months last year was that of literary labour enslaved by unwise commitment—which is nothing when the work comes // easily, but which is much when one cannot ‘in good conscience do bad work’, as someone whose name escapes me once said.

In thanking you, I’d also like to tell you how much I appreciate your abilities and psychological vision, and how it amuses me, when reading you, to find a singular likeness of temperament between what you express and what I feel on analogous points. Know that, despite my silence, this intellectual fraternity makes of you a distant friend of whom I often think. I’m delighted to learn from Henry James that you have regained your health under the skies where you have taken refuge. How I’d like to hope that we’ll meet one day, and that we’ll be able to exchange ideas in // person and speak of things that we both love equally. But you’ve truly chosen an almost inaccessible sanctuary, and I think with wistfulness that years ago I almost knocked on your door in Bournemouth. It was shortly after getting to know you intellectually, and I was prevented by another demon, the demon of no-confidence that makes us back away from the most desired encounters. That, sir, is a lot of devilry for a short note that ought to be all warmth and pleasure, since it allows me to show my gratefulness. Please accept it as a sincere handshake indeed and consider me your true and devoted like-minded friend.

Paul Bourget

Translation: Katherine Ashley

.

See also the former post on Katherine Ashley’s recent study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature

.

.

.

.

.

.

RLS on his father

Father and son relationships are often difficult, and the Stevenson family was no exception. For an idea of how this may have influenced RLS’s writings we need only think of the overbearing father figures in his fiction.

An interesting document in this regard is the record of his father’s ‘faculties’ (bodily and mental characteristics and aspects of personality) in the copy of Galton’s Records of Family Faculties in the library at Vailima and now at Yale, reproduced in Julia Reid’s Robert Louis Stevenson, Science and the Fin de Siècle:

Reid says this is ‘in Fanny’s hand’ but it seems clear to me that it is by Stevenson himself. Take the word ‘dark’:

and compare it with the same word in ‘Memoirs of Himself’ written in 1880:

Here we see the very typical R-shaped ‘k’ and the inverted-v ”r’. Other typical features (not shown here) are the lead-in line to the ‘f’ rising to a spur and the same in the case of the ‘b’ but the ‘p’ starting with a hook. Having studied Stevenson’s handwriting for some time, my opinion is that this is written by him not Fanny. This only makes the entry more interesting.

An interesting description

The description of ‘Character and temperament’ begins ‘choleric, hasty, frank, shifty‘. The adjective ‘hasty’ must be used in the sense of ‘quickly roused to anger; quick-tempered, irritable’ (OED). It is interesting that we find the same adjective applied to a father in Kidnapped

his gillies trembled and crouched away from him like children before a hasty father.

Kidnapped, ch. 23

Hastie is the first name of the white-haired Dr Lanyon in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and he is quick tempered in his outbursts against Jekyll (‘scientific balderdash’, ‘I am quite done with that person’), a habit of thoughtless and absolute rejection that makes him similar to Jekyll (who uses the same words as Lanyon when he twice repeats that he is ‘done with’ Hyde).

The last adjective is ‘shifty’. I don’t think that can mean ‘dishonest, not to be depended on’ etc. There’s no entry for the word in the Dictionary of the Scots Language but I can imagine it had a special use north of the border from two OED citations:

1859 […] The canny, shifty, far-seeing Scot

1888 W. Black [writer of the kaleyard school] In Far Lochaber xxiii She was in many ways a shifty and business-like young person

So it could have the positive meaning of ‘well able to shift for oneself’. But context is very important in determining meaning and here the other three adjectives are about the quality of interactions with others rather than such a practical ability, so perhaps we should search further. Some help comes from Stevenson’s use of the word in his essay on John Knox:

He was vehement in affection, as in doctrine. I will not deny that there may have been, along with his vehemence, something shifty, and for the moment only; that, like many men, and many Scotchmen, he saw the world and his own heart, not so much under any very steady, equable light, as by extreme flashes of passion, true for the moment, but not true in the long run.

Here ‘something shifty, and for the moment’ is associated with ‘vehemence’ and ‘passion’. It looks like a ‘shifty’ person is someone who changes position and beliefs as his passions dictate. Could this be the authoritarian person who can quickly justify any action?

Some more evidence of Stevenson’s use of the word is found in Weir of Hermiston (ch. 2), where the elder Kirstie has only the company of the maidservant

who, being but a lassie and entirely at her mercy, must submit to the shifty weather of “the mistress’s” moods without complaint, and be willing to take buffets or caresses according to the temper of the hour.

Here ‘shifty’ is associated with the changeable and unpredictable moods of an authoritarian person and this might fit Thomas Stevenson better.

Finally, in the company of the other three adjectives ‘frank’ probably doesn’t mean ‘open, sincere’ but more ‘candid, outspoken, unreserved’.

Not ‘To Schubert’s Ninth’

The present contribution has been kindly provided by John F. Russell

Beginning around 1890 Stevenson began compiling lists of contents for Songs of Travel like the following included in a letter to Edward Burlingame:

Letters 6: 371

One manuscript similar to the eleventh title on that list, To Schubert’s Ninth, is described by George McKay:

George L. McKay, A Stevenson Library (New Haven: Yale UP, 1961)

The title of what is probably the actual manuscript he describes is slightly different, however:

Yale, GEN MSS 664 Box 29 Folder 681

The underlined word McKay transcribed as “Ninth” lacks the dot over the letter “I” and the first letter is “M” not “N”. The correct transcription is the German word “Muth” (courage) and refers to song number XXII in Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise.

Booth and Mehew also transcribed the word incorrectly in letter 2211. In manuscript, the list for Songs of Travel appears as follows:

Yale, GEN MSS 664 Box 1 Folder 17 (= Letter 2211)

Enlarged, entry XI appears:

Shown side by side, the two words in manuscript are almost identical:

Title XI in the list of contents for Songs of Travel in letter 2211 therefore should read “To Schubert’s Muth” not “To Schubert’s Ninth.” Together the two manuscripts show conclusively that Stevenson’s poem ‘Vagabond’ was written to Schubert’s music for ‘Muth’ (in Winterreise) and not to any melody from Schubert’s Ninth Symphony.

RLS plans his volume of poems carefully

This post is contributed by John F. Russell, author and editor of The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson.

.

RLS, professional writer

(Richard Dury writes: in the previous post contributed by John F. Russell, I added an editorial aside: “An interesting puzzle for someone wold be to work out what all the numerical calculations mean”. John Russell has taken up the challenge and offers the following convincing solution, which shows how carefully RLS was planning the volume of poems:)

You issue a challenge to work out what all the numerical calculations mean in Beinecke 6896.

This is the first line:

30. 1. Ditty ….. 14 …… 807 ….. 1 …. 53

- 30 is the position of the item in the entire list of poems destined for Songs of Travel.

- 1 is the position in the section “Songs.”

- 14 is the number of lines in the poem (Lewis (Collected Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson) shows the 12 line version of Ditty on p. 178, but says on p. 496 there was a 14 line version). Madrigal (#5 on the list of “Songs”), for another instance, has 24 lines, the number given after the title on this list.

- 807 is the cumulative number of lines of poetry from the beginning of the list.

- 1 is the number of pages to be occupied by the poem.

- 53 is the page on which the poem starts. For instance, Vagabond (#3) starts on page 57 and occupies 2 pages. The next poem, Over the Sea to Skye (#4), occupies 2 pages and starts on p. 59. RLS must have envisioned a small format book. I don’t recall the reference, but I believe he insisted on only one poem per page.

.

(Richard Dury writes: Chapeau!)

Songs of Travel manuscript puzzle solved

This post is contributed by John F. Russell, author and editor of The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson.

.

List of poems for what became ‘Songs of Travel’

Songs of Travel is a posthumous collection of poems first published in 1895 (in vol. XIV of the Edinburgh Edition), but already planned by Stevenson before his death. Among the draft outlines of the collection is Beinecke ms. 6895.

This ms. is divided into four sections and lists 43 poems, many of which later appeared in Songs of Travel. The section “Songs” contains 13 items and appears below.

(Note how RLS, the professional writer, is able to predict this will occupy “21 pp” in the note bottom left.)

The manuscript is transcribed by Roger C. Lewis on pp. 480-481 of his Collected Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson, where he says that title number 10 is illegible. His reluctance to guess the title is understandable, as readers will discover if they interpret the title as something like “Cr… & Sev…”:

However, a quick look at other RLS manscripts shows that he rarely closes the loop of a capital A, and it often looks like “C” instead. Knowing that, it is much easier to see that title number 10 in fact reads “Aubade & Serenade.”

Aubade and Serenade

Of course there is no RLS poem with this title. However the preceding numbers 8 and 9 on the list are the familiar “I will make you brooches” and “In the highlands” found towards the beginning of Songs of Travel. So what was “Aubade and Serenade”?

Beinecke ms. 6896 is similar to 6895 but contains a list of 19 items under the heading “Songs”, including all the titles in ms. 6895:

(An interesting puzzle for someone would be to work out what all the numerical calculations mean.)

In this longer list, “I will make you brooches” is again no. 8, and no. 9 is again “In the highlands.” Number 10 is “Let beauty awake.”

“Let Beauty Awake” is a two stanza poem in which the first is about the morning and the second about the evening. An aubade is a song for the morning while a serenade is for the evening.

So I conclude that item number 10 in both lists is the same and that “Aubade & Serenade” is “Let beauty awake.”

John F. Russell

Stevenson’s Montaigne, part 3

Stevenson’s markings and comments

Entering a ‘Rare Books’ room is a privilege: the Library’s first-class compartment, away from the crowds, there you are, entrusted with precious volumes, acquiring a new-found elegance as you turn over manuscript leaves; maybe someone will take me for a real scholar…

The four volumes of Stevenson’s Montaigne had so many markings that I was unsure how to combine this elegant slowness with noting down all the information in the short time available. In the end, I decided just to note the special markings: not the single vertical marks in the margin but only the double lines, then the underlinings and finally the added comments. Even so, listing them all will not have much meaning, so here I’ll group them into rough categories according to what makes them interesting. Rather than give the French text I have given Cotton’s translation of the passages, using blue for Montaigne’s text (or translation of it) and red for Stevenson’s added comments.

1. Endpaper annotations

Here, on the recto page of the inside front cover of volume 4 is Stevenson’s concise characterization of Montaigne. Above it is ‘p 44’ which seems to refer to the following marked passage on p. 44 in the essay ‘Of Cripples’ (III. 11):

I have never seen greater monster or miracle in the world than myself: one grows familiar with all strange things by time and custom, but the more I frequent and the better I know myself, the more does my own deformity astonish me, the less I understand myself.

The only other flyleaf annotation is at the back of vol. 2, a list of 11 names all but one crossed through. They are written very faintly, but they are possibly all place-names as the only one I was able to decipher was ‘Abbotsford’. This is a mystery which someone else will have to solve.

.

2. Marginal comments: a personal dialogue with the text

Most of the marginal comments are in vols. 3 and 4, in Montaigne’s Book III, which, as we have already seen, was the part Stevenson seems to have read most intensely.

2.1 Disagreements

Some of the comments show Stevenson’s disagreement:

Vol. 2, p. 205 (Apology for Raymond Sebond): here Montaigne says (probably following here Sebond’s Fideistic arguments, which he is subtly undermining), concerning ancient predictions from the flight of birds ‘That rule and order of the moving of the wing, whence they derived the consequences of future things, must of necessity be guided by some excellent means to so noble an operation: for to attribute this great effect to any natural disposition, without the intelligence, consent, and meditation of him by whom it is produced, is an opinion evidently false.‘ This clearly doesn’t square with the normal skepticism of Montaigne and Stevenson and the latter adds ! an exclamation mark in the margin.

Vol. 2, p. 598 (Of Presumption): against the passage ‘It is very easy to accuse a government of imperfection, for all mortal things are full of it: it is very easy to beget in a people a contempt of ancient observances; never any man undertook it but he did it‘, RLS (probably thinking of how resistant established orders were to change) has added ‘false‘.

Vol. 3,p. 207 (Of Profit and Honesty): the footnote translation of “Dum tela micant etc.’ is introduced by the editor in these words ‘De Jules César, qui, en guerre ouverte contre sa patrie, dont il veut opprimer la liberté, s’écrie dans Lucain, […]’—RLS comments on this fiercely Republican interpretation of the editor with: ‘O! O!‘.

2.2 Glosses

On several occasions Stevenson complained about translations that were accurate but dull, and here in Vols. 3 and 4 we have a good number of his own translation glosses on about twenty separate pages. Some of these show his preference for telling translations: for the French translated by Cotton as ‘Rough bodies make themselves felt’, he has ‘knotty surfaces are sensible‘ (Vol. 3, p. 33), where Cotton has ‘crowd‘ he has ‘ruck‘ (vol. 4, p. 35). Where Montaigne talks of childhood games ‘aux noisettes et à la toupie‘ (vol 3, p. 269), Stevenson is clearly pleased to see the long survival of games with which he was familiar and writes ‘huckle bones and tops!‘

2.3 Other comments

Vol. 2, p. 197 (Raymond Sebond, II, 12): Montaigne says that nightingales while learning to sing ‘contention [i.e. they compete] with emulation‘. Here RLS has added in the margin ‘I have observed this in blackbirds‘.

Vol. 3, p. 186 (Of Profit and Honesty): In the passage translated by Cotton as ‘for even in the midst of compassion we feel within, I know not what tart-sweet titillation of ill-natured pleasure in seeing others suffer‘, Stevenson glosses ‘au milieu de la compassion‘ as ‘in the very midst of pitying‘; ‘aigredouce poincte de volupté maligne‘ as ‘prick of malignant pleasure‘ and then adds an additional note at the foot of the page: ‘ay, & cruelty also, that so unnatural defect‘.

date

3. Markings: echoes of Stevenson’s ideas

Not all the markings (underlinings and vertical lines in the margin) remind one of Stevenson’s writings: he marks the passages that perhaps strike every reader of Montaigne: the passage where Montaigne talks of his cat playing with him (‘When I play with my cat who knows whether I do not make her more sport than she makes me?‘, Vol. 2, p. 177-8); Montaigne’s frankness about sex and the differences between men and women (in ‘Upon some verses of Virgil’ in Book III) receives a predictable number of markings (a double line for ‘the pleasure of telling [about sex] (a pleasure little inferior to that of doing)‘ is accompanied by ! an exclamation mark in the margin, Vol. 3, p. 304); his openness about other bodily functions (‘Both kings and philosophers go to stool, and ladies too‘, Vol. 4, p. 133—a single line and an ‘x‘ in the margin); and his ability to focus on the moment and ‘just be’ (‘When I dance, I dance; when I sleep, I sleep. Nay, when I walk alone in a beautiful orchard, if my thoughts are some part of the time taken up with external occurrences, I some part of the time call them back again to my walk, to the orchard, to the sweetness of that solitude, and to myself‘, Vol. 4, p. 174, ‘Of Experience’).

However, a good number of the markings do remind us of Stevenson’s own thoughts and writings. Here follow a few that struck me.

3.1 Courage

Stevenson’s idea that in an inevitably tragic life one should act courageously clearly has affinities with the stoicism of Montaigne. We saw in a previous post that the acceptance of a kind gradual death at the end of ‘Ordered South’ has affinities in an unmarked essay in Stevenson’s Vol. 1—but it also has an affinity with a double-marked passage in Montaigne’s last essay, ‘Of Experience’, which talks of how death ‘weans thee from the world‘ and how thanks to its frequent reminders accustoms you to the idea of death and ‘thinking thyself to be upon the accustomed terms, thou and thy confidence will at one time or another be unexpectedly wafted over‘ (Vol. 4, p. 144).

The idea that life must be faced with the joy and courage of a soldier in war (L6, 153, and Abrahamson in Persona and Paradox, 2012) is also echoed in another marked passage from the same essay: ‘Death is more abject, more languishing and troublesome, in bed than in a fight: fevers and catarrhs as painful and mortal as a musket-shot. Whoever has fortified himself valiantly to bear the accidents of common life need not raise his courage to be a soldier‘ (Vol. 4, p. 152).

3.2 Modesty

I think we can detect a basic modesty in Stevenson’s world-view, and he seems certainly to have been struck by that of Montaigne as we see from the following marked passages.

Vol. 2, p. 473 (Of Presumption): ‘I look upon myself as one of the common sort, saving in this, that I have no better an opinion of myself; guilty of the meanest and most popular defects, but not disowning or excusing them; and I do not value myself upon any other account than because I know my own value.’

Vol. 3, p. 193 (Of Profit and Honesty): ‘keeping my back still turned to ambition; but if not like rowers who so advance backward.’

Vol. 3, p. 392 (On the Inconvenience of Greatness) (with three vertical marks): ‘I would neither dispute with a porter, a miserable unknown, nor make crowds open in adoration as I pass.’

3.3 Instability, constant change

Stevenson frequently expresses the idea of a world in constant change (‘Times and men and circumstances change about your changing character, with a speed of which no earthly hurricane affords an image’, ‘Lay Morals’) and this will explain his double-line marking of the following passage in Montaigne:

Vol. 3, p. 209 (Of Repentance): ‘the world eternally turns round; all things therein are incessantly moving, the earth, the rocks of Caucasus, and the pyramids of Egypt, both by the public motion and their own. Even constancy itself is no other but a slower and more languishing motion‘ (this is Cotton’s translation cited here for convenience; For ‘un branle‘ which Cotton translates ‘motion‘, Stevenson suggests in the margin: ‘tottering?‘).

3.4 Laws and civil society

Roslyn Joly has recently shown the importance of Stevenson’s legal education in his world-view (‘The Novelist as Lawyer’ in Robert Louis Stevenson in the Pacific, 2009), and we can see this interest behind a series of other markings:

Vol 3, p. 212 (Of Repentance): ‘I hold for vices (but every one according to its proportion), not only those which reason and nature condemn, but those also which the opinion of men, though false and erroneous, have made such, if authorised by law and custom.’ (And here RLS unusually translated the whole sentence: : ‘I hold then this for vices (but each according to its measure) not only which reason and nature have condemned, but which the opinion of men has most erroneously forbidden in their laws and usages.’)

Vol 3, p. 332 (Upon some verses of Virgil): ‘Thou dost not stick to infringe her universal and undoubted laws; but stickest to thy own special and fantastic rules, and by how much more particular, uncertain, and contradictory they are, by so much thou employest thy whole endeavour in them: the laws of thy parish occupy and bind thee: those of God and the world concern thee not.’ (This idea of the importance of ‘les regles de ta parroisse‘ may be linked to a discussion in ‘On Morality’ (an unfinished essay of 1888) of how ‘Crime is a legal, a merely municipal expression’.)

3.5 Style

Naturally Stevenson is attentive to what Montaigne says about literary style:

Vol 2, p. 119 (Of Books): ‘and the ladies are less put to it in dance; where there are various coupees, changes, and quick motions of body, than in some other of a more sedate kind, where they are only to move a natural pace, and to represent their ordinary grace and presence‘ (i.e. a plain style requires more ability than one full of ‘changes, and quick motions’—though we might think the latter characterizes some of Stevenson’s own earliest writings).

The following two marked passages close together remind me of Stevenson’s own intense work of thought in his his essays and how he says in ‘Walt Whitman’ ‘style is the essence of thought’:

Vol 3,p. 321 (Upon some verses of Virgil): ‘When I see these brave forms of expression, so lively, so profound, I do not say that ’tis well said, but well thought. ‘Tis the sprightliness of the imagination that swells and elevates the words.’

Vol 3, p. 322 (Upon some verses of Virgil): ‘The handling and utterance of fine wits is that which sets off language; not so much by innovating it, as by putting it to more vigorous and various services, and by straining, bending, and adapting it to them. They do not create words, but they enrich their own, and give them weight and signification by the uses they put them to, and teach them unwonted motions, but withal ingeniously and discreetly.’

And Stevenson’s own preference for concision can be seen as motivating the following underlining concerning Cicero’s style:

Vol 2, p. 121-2 (Of Books): ‘whatever there is of life and marrow is smothered and lost in the long preparation‘.

.

4. Markings: some closer affinities with Stevenson’s works

These categories of markings are only intended to make the matter a little more understandable; clearly this and the previous category are closely connected. Here are some echoes (interesting echoes, not provable influences) of works I am familiar with:

‘Crabbed Age and Youth’—Vol 3, p. 223-4 (Of Repentance): ‘When I reflect upon the deportment of my youth, with that of my old age, I find that I have commonly behaved myself with equal order in both according to what I understand‘; and Vol 4, p. 186, an underlined passage: ‘Old age stands a little in need of a more gentle treatment. Let us recommend that to God, the protector of health and wisdom, but let it be gay and sociable.’

‘Ordered South’: I have already remarked on a passage that reminded me of this in 3.1

‘An Apology for Idlers’—an underlining in Vol 4, p. 172 (of Experience): ‘We are great fools. “He has passed his life in idleness,” say we: “I have done nothing to-day.” What? have you not lived?‘;

‘Something In It’ (where the missionary feels bound to his vow of abstinence)—Vol 3, p. 201: ‘what fear has once made me willing to do, I am obliged to do it when I am no longer in fear; and though that fear only prevailed with my tongue without forcing my will, yet am I bound to keep my word‘, Stevenson has in the margin written, ‘to prove sound the links of my honour‘.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde—an underlining in Vol 3, p. 274 (Upon some Verses of Virgil): ‘A man must see and study his vice to correct it; they who conceal it from others, commonly conceal it from themselves‘.

‘Lay Morals’ (the first paragraph of Ch. III where he talks of the frailty of man ‘His whole body, for all its savage energies, its leaping and its wing’d desires, may yet be tamed and conquered by a draught of air or a sprinkling of cold dew’ etc.)—Vol 2, p. 214 (Raymond Sebond): ‘this furious monster, with so many heads and arms, is yet man–feeble, calamitous, and miserable man! […] a contrary blast, the croaking of a flight of ravens, the stumble of a horse, the casual passage of an eagle, a dream, a voice, a sign, a morning mist, are any one of them sufficient to beat down and overturn him. Dart but a sunbeam in his face, he is melted and vanished. Blow but a little dust in his eyes, as our poet says of the bees, and all our ensigns and legions, with the great Pompey himself at the head of them, are routed and crushed to pieces.’

The poem ‘Home, no more home to me, whither shall I wander?’ and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (‘a stranger in my own house’)—Vol 3, p. 248 (Of Three Commerces): ‘That man, in my opinion, is very miserable, who has not at home where to be by himself, where to entertain himself alone, or to conceal himself from others.’ We don’t know why Stevenson marked this passage, but it is possible that he felt that he did not possess such a space—Montaigne, however, is not complaining at all but talking about his own rule of living, which he had previously formulated in more positive terms: ‘we must reserve a backshop, wholly our own and entirely free, wherein to settle our true liberty, our principal solitude and retreat’ (‘Of Solitude’, I.38).

.

5. This edition used for quotations from Montaigne

Where there is a marking of a passage that is quoted in a letter or one of his works, then there is a good chance that this was the edition used. There are, however, only two or three possible cases, since Stevenson only quotes twice (I think) from Montaigne in French:

Vol 2, p. 13 (Of Drunkenness), an underlined passage: ‘and there are some vices that have something, if a man may say so, of generous in them‘ (‘il y a des vices, qui ont je ne sçay quoy de genereux‘), quoted in ‘The Character of Dogs’ (1883), “The canine, like the human gentleman demands in his misdemeanours Montaigne’s ‘je ne sais quoi de généreux'”. Here Montaigne’s spelling has been modernized, but that could have been done by Stevenson or the magazine editor.

Vol. 4 (‘Of Physiognomy’): Stevenson quotes a passage from the first half of this essay in his latter of October 1873 to Fanny Sitwell (L1, 339):

As Montaigne says, talking of something quite different: ‘Pour se laisser tomber à plomb, et de si haut, il faut que ce soit entre les bras d’une affection solide, vigoureuse et fortunée’ It argues a whole faith in the sympathy at the other end of the wire; and an awful want to say these things.

I did not note this down as a passage doubly-marked. It is possibly singly marked, but this will have to wait for another reader to open the volume.

The third case has already been discussed on Part two of this posting, under ‘Book III’: in ‘Crabbed Age and Youth’ (1877) Stevenson writes that while Calvin and Knox are reforming the church, Montaigne is ‘predicting that they will find as much to quarrel about in the Bible as they had found already in the Church’—a possible allusion to ‘Of Experience’ (III.13): ‘they but fool themselves, who think to lessen and stop our disputes by recalling us to the express words of the Bible‘, against which Stevenson has written in the margin ‘Calvin?‘

.

Montaigne and Stevenson

Stevenson seems to have found in Montaigne a fellow-spirit, someone who distrusted dogma yet had a moral view of life, a modest and a tolerant person, a skeptic, someone who saw all things in constant change yet kept a calm, detached and ironic view of things. Both writers were constantly interested in exploring how to live life well.