Archive for the ‘MS transcription’ Category

Paul Bourget writes to Stevenson

A post contributed by Katherine Ashley

In 1891, Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Paul Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (1891). The book gave Stevenson a ‘literal thrill’ and he quickly requested more of his works. Bourget (1852-1935) was a poet, novelist, and playwright, but today he is mainly read by literary historians for his astute study of fin de siècle cultural malaise, Essais de psychologie contemporaine (1885). He was also, like Stevenson, a traveller, and it is fitting that Stevenson’s introduction to him was via Sensations d’Italie, a book about Bourget’s travels in Tuscany, Umbria and Puglia.

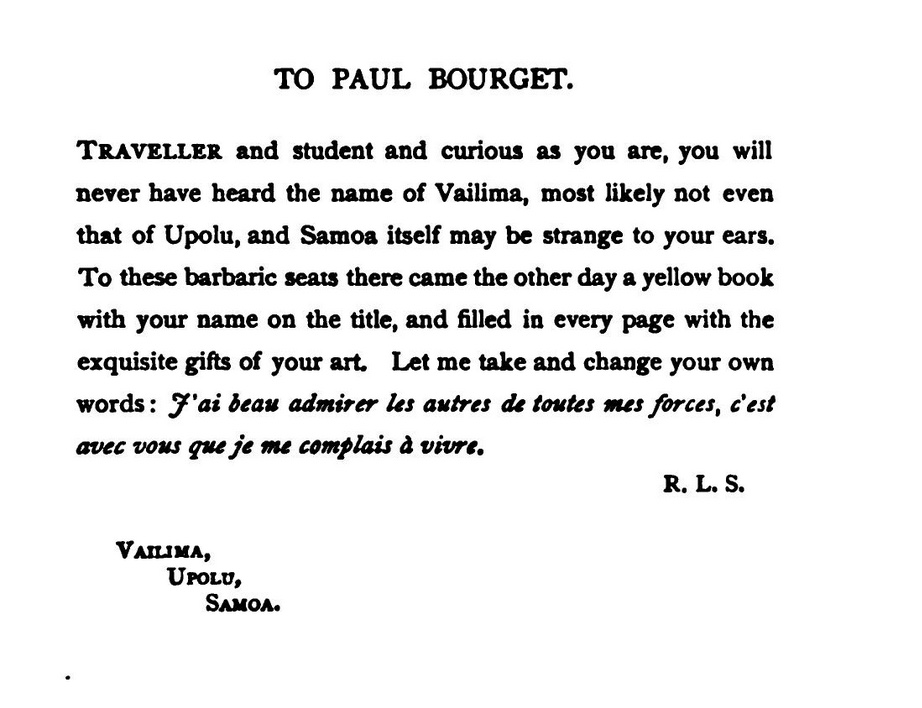

The reasons for Stevenson’s enthusiasm for Sensations d’Italie are explored in an earlier post; a direct result of his reading is that he dedicated Across the Plains (1892) to Bourget.

To Stevenson’s consternation, Bourget did not immediately respond to the compliment. He complained to Sidney Colvin: ‘ain’t it manners in France to acknowledge a dedication? I have never heard a word from le Sieur Bourget, drat his impudence!’. He was even more to the point in a letter to James. Although the tone is good-humoured, there is an element of hurt and annoyance:

I thought Bourget was a friend of yours? And I thought the French were a polite race? He has taken my dedication with a stately silence that has surprised me into apoplexy. Did I go and dedicate my book to the nasty alien, and the ’n’orrid Frenchman, and the Bloody Furrineer? Well, I wouldn’t do it again; and unless his case is susceptible of Explanation, you might perhaps tell him so over the walnuts and the wine, by way of speeding the gay hours. Seriously, I thought my dedication worth a letter.

As it turns out, Bourget’s case was indeed ‘susceptible of Explanation’: work had prevented him from replying. The excuse seems reasonable, since Bourget spent the first months of 1892 in Rome, which resulted in his novel Cosmopolis (1893). He also published two other books around this time, La Terre promise (1892) and Un scrupule (1893).

Bourget’s contrite reply finally came, enclosed in James’s next letter to Stevenson. The manuscript is kept at Harvard University. It is transcribed and translated here.

Londres, le 3 août 93

Monsieur et cher confrère,

Je suis si coupablement en retard avec vous pour vous remercier de la dédicace du beau livre en tête duquel vous avez mis mon nom que je n’en finirais pas de m’en excuser. Le démon de la procrastination—ce mauvais génie de tous les imaginatifs—m’a joué des tours cruels dans ma vie. Il aurait commis le pire de ses méfaits s’il m’avait privé de la précieuse sympathie dont témoignait votre envoi—et venant de l’admirable artiste que vous êtes, cette sympathie m’avait tant touché. Peut-être trouverez-vous le mot de cette énigme de paresse dans une existence qui six mois durant, l’année dernière, a été celle d’un manœuvre littéraire esclavagé par un engagement imprudent—ce qui n’est rien lorsqu’on a le travail // facile, ce qui est beaucoup quand on ne peut pas « faire consciencieusement mauvais » comme disait je ne sais plus qui.

J’aurais voulu aussi, en vous remerciant, vous dire combien j’aime votre faculté et vision psychologique et comme il m’amuse en vous lisant de trouver entre ce que vous exprimez et ce que je sens sur des points analogues de singulières ressemblances d’âme. Croyez que, malgré mon silence, cette fraternité intellectuelle fait de vous un ami éloigné auquel je pense souvent. Je me réjouis de savoir par Henry James que vous avez retrouvé la santé sous le ciel où vous êtes réfugié. Que je voudrais pouvoir espérer qu’un jour nous nous rencontrerons, et que nous pourrons de vive // voix échanger quelques idées et parler des choses que nous aimons également ! Mais vous avez vraiment choisi l’asile presque inaccessible et je songe avec mélancolie que j’ai failli, voici des années, aller frapper à votre porte à Bournemouth. C’était un peu après vous avoir connu intellectuellement, et un autre démon, celui de la défiance, qui fait qu’on recule devant les rencontres les plus désirées, m’en a empêché. Voilà, Monsieur, beaucoup de diableries dans un petit billet qui devrait être toute chaleur et toute joie puisqu’il me permet de vous prouver ma gratitude d’esprit. Recevez-le comme une poignée de main bien sincère et croyez moi votre vrai et dévoué ami d’esprit.

Paul Bourget

Transcription: Katherine Ashley, Antoine Compagnon and Richard Dury

.

London, 3 August 1893

My dear fellow,

I am so shamefully late in thanking you for the dedication to the fine book at the front of which you put my name, that I’ll never be done asking for forgiveness. The demon of procrastination—that evil genie of all creative people—has played cruel tricks in my life. He will have perpetrated his worst mischief if he has deprived me of the precious sympathy demonstrated by your dedication—and coming from the admirable artist that you are, this sympathy has touched me greatly. Perhaps you’ll find an explanation for my mysterious slowness in an existence that for six long months last year was that of literary labour enslaved by unwise commitment—which is nothing when the work comes // easily, but which is much when one cannot ‘in good conscience do bad work’, as someone whose name escapes me once said.

In thanking you, I’d also like to tell you how much I appreciate your abilities and psychological vision, and how it amuses me, when reading you, to find a singular likeness of temperament between what you express and what I feel on analogous points. Know that, despite my silence, this intellectual fraternity makes of you a distant friend of whom I often think. I’m delighted to learn from Henry James that you have regained your health under the skies where you have taken refuge. How I’d like to hope that we’ll meet one day, and that we’ll be able to exchange ideas in // person and speak of things that we both love equally. But you’ve truly chosen an almost inaccessible sanctuary, and I think with wistfulness that years ago I almost knocked on your door in Bournemouth. It was shortly after getting to know you intellectually, and I was prevented by another demon, the demon of no-confidence that makes us back away from the most desired encounters. That, sir, is a lot of devilry for a short note that ought to be all warmth and pleasure, since it allows me to show my gratefulness. Please accept it as a sincere handshake indeed and consider me your true and devoted like-minded friend.

Paul Bourget

Translation: Katherine Ashley

.

See also the former post on Katherine Ashley’s recent study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature

.

.

.

.

.

.

An unpublished letter from Stevenson to Violet Paget (Vernon Lee), 1885

This post is contributed by Lesley Graham, presently working on Uncollected Essays 1880–1894 for the Edition.

Earlier this year a manuscript letter by Robert Louis Stevenson was found by Petersfield Bookshop between the pages of a volume of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Letters to his Family and Friends (ed. Sydney Colvin). The bookshop posted photographs of the two-page letter to their Twitter account (23 July 2019). The letter does not appear in the eight-volume Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson (Yale Univ. Press, 1994-5) and is transcribed below for the first time.

Violet Paget (1856–1935) wrote under the pseudonym Vernon Lee. She was an essayist, travel writer, critic and author of supernatural and short fiction with a scholarly interest in eighteenth-century Italy. When this letter was written in 1885, having lived in various parts of Europe, she was dividing her time between her family home in Florence and extended visits to England. She and Stevenson shared many friends and acquaintances — Henry James, J. A. Symonds, Horatio Brown, John Singer Sargent, Anne Jenkin etc. — but they do not appear ever to have met in person. Two letters from Paget to Stevenson are held in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, but have never been published in full (Yale, GEN MSS 664 box 17 folder 453; B 5363-5364). The earlier of these is dated 6th August 1885 and written on stationery marked 5 via Garibaldi, Florence. It is Paget’s first contact with Stevenson and clearly prompted the reply published here. The second is dated August 10, 1886. Stevenson’s unfinished reply to this later letter appears in The Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson (vol. 5, p. 306).

Stevenson’s letter touches on three topics: a discussion of the necessary permissions for the translation of two of his works into Italian; acknowledgment of receipt of a work by Vernon Lee, and most interestingly a sympathetic discussion of the character of Prince Charles Edward Stuart and what Stevenson sees as Vernon Lee’s unflattering and one-sided treatment of him as a repulsive drunk in her account of the life of his wife (Princess Louise Maximilienne Caroline Emmanuele of Stolberg-Gedern, 1752–1824) in The Countess of Albany (London: W. H. Allen, 1884). Stevenson mentioned the prince in Kidnapped the following year, 1886:

‘the Prince was a gracious, spirited boy, like the son of a race of polite kings, but not so wise as Solomon. I gathered, too, that while he was in the Cage, he was often drunk; so the fault that has since, by all accounts, made such a wreck of him, had even then begun to show itself. (R. L. Stevenson, Kidnapped (London: Penguin, 1996), p. 162)

He was also to write about the Prince several years later in the novel fragment The Young Chevalier (1892), which paints a brief but psychologically nuanced portrayal of

a boy at odds with life, a boy with a spark of the heroic, which he was now burning out and drowning down in futile reverie and solitary excess (in Weir of Hermiston and other fragments, the Edinburgh Edition, vol. 26 (Edinburgh: Constable, 1897), pp. 82–3)

— a portrait in line with the plea for indulgence expressed in this letter. (For more on Stevenson’s treatment of the Young Pretender, see Lesley Graham, “Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘The Young Chevalier’: Unimagined Space”, in Macinnes, German & Graham (eds), Living with Jacobitism, 1690-1788: The Three Kingdoms and Beyond (London : Pickering & Chatto, 2014), pp. 63–83.)

The bottom right hand corner of the first page of the letter is torn and the ends of four lines are consequently missing. In each case, our best guess as to the missing words or letters has been inserted between square brackets with a question mark.

Skerryvore

Bournemouth

Oct 14. 1885Dear Madam,

I shall attend to the affair of Signora Santarelli [1] with my best diligence, which is a relative diligence. It is right, however, that I should explain to you how I stand. If the permission be granted in the case of the first series it will be of the grace of Messrs Chatto & Windus; and if in the case of the second, [2] Signora Santarelli will have to divide her thanks between the authors and Messrs Longman. So far as the authors are concerned, it is already done; neither my wife nor I would dream of denying any invalid what may possibly prove to be an entertainment: we have both unfortunately too much reason to sympathise with the sick.Your Prince [3] has arrived only this morning; and I have only read the introduction: if the rest be at all of a piece with it, you have sent me a great treat.

I believe we have two more common friends than you all[ude?] to [4]: Symonds [5] and Prince Charlie. I, who had mostly s[tolen?] the bright pages of Charle’s [sic] Stuart’s life, felt it as perhaps[s a?] defect in your very interesting “Countess of Albany”, that yo[u had] failed to bring out the contrast. He was a bright boy; rather he was the bright boy of history, full of dash, full of endurance[,] full of a superficial [6] generosity, of blood more than of mind; he lived through great feats and dangers not unworthily. I should have liked perhaps, if you could not screw out a tear over so base a fall, that you had smiled a little sadly. We may all fall as low before we are done with it, and not have the picturesque and generous to look back upon. And indeed if you introduce your pretty countess to the bottle and keep her for months in Hebridean caves [7] with no other consolation, I suspect she would sink as low.

I am a fault finder in grain [8] and you must not wonder if I sieze [sic] on the occasion of your letter to pick this quarrel which I have long been musing.

(I am amused at the way in which I have bracketed the living lion and the dead dog, [9] but I meant no disrespect to either, surely not to Symonds), With many thanks Believe me

Yours truly

Robert Louis StevensonMiss Paget.

NOTES

[1] Signora Sofia Fortini-Santarelli: translator, wife of Cavaliere Emilio Santarelli of Florence who owned relics of the Young Pretender. She translated various works of Herbert Spencer, Ouida, and Symonds’s The Renaissance in Italy. In her letter, Paget describes her as “a lady who has taken to translating for the pastime which her recuperation affords her in a maiming & incurable malady”.

[2] the first series … the second: New Arabian Nights (1882) and More New Arabian Nights: The Dynamiter(1885). The latter was written in collaboration with Fanny Van de Grift Stevenson.

[3] Your Prince: Vernon Lee, The Prince of the Hundred Soups: A Puppet Show in Narrative (1883), a harlequinade.

[4] common friends: Paget had mentioned Henry James and John Sargent as friends they had in common.

[5] Symonds: John Addington Symonds (1840-1893), essayist, poet, and biographer best known for his cultural history of the Italian Renaissance.

[6] superficial: after this word Stevenson wrote, then deleted, ‘and not very wise’.

[7] in Hebridean caves: Charles hid out in some remote refuges in Benbecula and South Uist between April and June 1746.

[8] in grain: through and through, by nature (from ‘dyed in grain’, ingrained).

[9] the living lion and the dead dog: i.e. the two “acquaintances” they have in common: J. A. Symonds and Charles Edward Stuart.

Lesley Graham

University of Bordeaux

Following the author’s hand

A post contributed by Gill Hughes

editor of Stevenson’s Weir of Hermiston in the New Edinburgh Edition

A series of speculations

It is in working on a manuscript that an editor comes closest to the author, and in the case of Weir of Hermiston the manuscript record is unusually rich and full, comprising a wealth of draft material in Stevenson’s own hand as well as a final (though not finished) manuscript dictated by him to his step-daughter and amanuensis, Belle Strong. Following the author’s progress exerts an irresistible charm.

Stevenson himself, that great collaborator, plainly understood the attractions of watching the writer at work, for he invites the reader close to the narrator in the final text of Weir of Hermiston. The narrator’s account of the unpopularity of Frank Innes at Hermiston, for example, proceeds as a series of speculations, a gradual approach to the most plausible explanation.

Firstly the narrator posits that Frank’s technique of depreciation by means of a confidential conspiracy fails because of the admiration felt by the estate folk for both Lord Hermiston and Archie himself. Subsequently he reconsiders, deciding that in Frank’s condescension as displayed to Dand Elliott, ‘we have here perhaps a truer explanation of Frank’s failures’.

The reader is invited to participate in the narrator’s working out of the situation, the gradual evolution of an accurate apprehension.

A succession of drafts.

This process forms a curious parallel to the way in which Stevenson’s draft manuscript revisions operate. A situation envisaged by the author is reiterated and reassessed in a succession of drafts until he is satisfied with his representation and only then does he move forward again in his story. None of the draft material for Weir moves very much past the point at where the final manuscript breaks off, but there are multiple surviving attempts at earlier key passages—at least five, for instance, for the start of the first chapter where Stevenson was getting his narrative underway, and several for subsequent key points in the narrative that required peculiar care.

Chief among these are the interval between the execution of Duncan Jopp and Lord Hermiston’s confrontation of his rebellious son, and the forming of a bond between Archie and the younger Kirstie after their initial sighting of one another in Hermiston kirk. Stevenson’s revisions show how very far he is himself from the leisurely speculations of his narrator. He moves always from the explicit to the implicit, cutting out details that would make any writer of realist fiction proud. His draft description of Archie’s motherless childhood in the house in George Square, for instance, sticks in the memory:

That was a severe and silent house; the tall clocks ticked and struck there, the bell rang for meals; and beyond these periodic sounds, and the clamour of an occasional deep drinking dinner, it was a house in which a pin might be heard dropping from one room to another. […] When my lord was at home, the servants trembled and hasted on noiseless feet, the child kept himself trembling company in the tall rooms, and had but one concern—to avoid his father’s notice. (Morgan MA 1419, f. 17)

The child’s isolation in the tall rooms of a house could not be more vividly portrayed and yet Stevenson ultimately judged it inessential to the novel.

An editor’s experience

In editing Stevenson’s Weir of Hermiston one is brought close to a narrator who can seem prolix and provisional, an amiable and indulgent fellow-traveller through the story, but standing close beside him is a most painstaking and most uncomfortably ruthless artist. ‘That’s wonderful!’ I wanted to say to Stevenson of this passage in his draft material and of that. ‘Couldn’t you have left that bit in?’ But he pared back his own imaginative fecundity with an unsparing hand, and here and there in the editorial material I’ve tried to indicate where he has done it.

Not ‘To Schubert’s Ninth’

The present contribution has been kindly provided by John F. Russell

Beginning around 1890 Stevenson began compiling lists of contents for Songs of Travel like the following included in a letter to Edward Burlingame:

Letters 6: 371

One manuscript similar to the eleventh title on that list, To Schubert’s Ninth, is described by George McKay:

George L. McKay, A Stevenson Library (New Haven: Yale UP, 1961)

The title of what is probably the actual manuscript he describes is slightly different, however:

Yale, GEN MSS 664 Box 29 Folder 681

The underlined word McKay transcribed as “Ninth” lacks the dot over the letter “I” and the first letter is “M” not “N”. The correct transcription is the German word “Muth” (courage) and refers to song number XXII in Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise.

Booth and Mehew also transcribed the word incorrectly in letter 2211. In manuscript, the list for Songs of Travel appears as follows:

Yale, GEN MSS 664 Box 1 Folder 17 (= Letter 2211)

Enlarged, entry XI appears:

Shown side by side, the two words in manuscript are almost identical:

Title XI in the list of contents for Songs of Travel in letter 2211 therefore should read “To Schubert’s Muth” not “To Schubert’s Ninth.” Together the two manuscripts show conclusively that Stevenson’s poem ‘Vagabond’ was written to Schubert’s music for ‘Muth’ (in Winterreise) and not to any melody from Schubert’s Ninth Symphony.

RLS plans his volume of poems carefully

This post is contributed by John F. Russell, author and editor of The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson.

.

RLS, professional writer

(Richard Dury writes: in the previous post contributed by John F. Russell, I added an editorial aside: “An interesting puzzle for someone wold be to work out what all the numerical calculations mean”. John Russell has taken up the challenge and offers the following convincing solution, which shows how carefully RLS was planning the volume of poems:)

You issue a challenge to work out what all the numerical calculations mean in Beinecke 6896.

This is the first line:

30. 1. Ditty ….. 14 …… 807 ….. 1 …. 53

- 30 is the position of the item in the entire list of poems destined for Songs of Travel.

- 1 is the position in the section “Songs.”

- 14 is the number of lines in the poem (Lewis (Collected Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson) shows the 12 line version of Ditty on p. 178, but says on p. 496 there was a 14 line version). Madrigal (#5 on the list of “Songs”), for another instance, has 24 lines, the number given after the title on this list.

- 807 is the cumulative number of lines of poetry from the beginning of the list.

- 1 is the number of pages to be occupied by the poem.

- 53 is the page on which the poem starts. For instance, Vagabond (#3) starts on page 57 and occupies 2 pages. The next poem, Over the Sea to Skye (#4), occupies 2 pages and starts on p. 59. RLS must have envisioned a small format book. I don’t recall the reference, but I believe he insisted on only one poem per page.

.

(Richard Dury writes: Chapeau!)

Songs of Travel manuscript puzzle solved

This post is contributed by John F. Russell, author and editor of The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson.

.

List of poems for what became ‘Songs of Travel’

Songs of Travel is a posthumous collection of poems first published in 1895 (in vol. XIV of the Edinburgh Edition), but already planned by Stevenson before his death. Among the draft outlines of the collection is Beinecke ms. 6895.

This ms. is divided into four sections and lists 43 poems, many of which later appeared in Songs of Travel. The section “Songs” contains 13 items and appears below.

(Note how RLS, the professional writer, is able to predict this will occupy “21 pp” in the note bottom left.)

The manuscript is transcribed by Roger C. Lewis on pp. 480-481 of his Collected Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson, where he says that title number 10 is illegible. His reluctance to guess the title is understandable, as readers will discover if they interpret the title as something like “Cr… & Sev…”:

However, a quick look at other RLS manscripts shows that he rarely closes the loop of a capital A, and it often looks like “C” instead. Knowing that, it is much easier to see that title number 10 in fact reads “Aubade & Serenade.”

Aubade and Serenade

Of course there is no RLS poem with this title. However the preceding numbers 8 and 9 on the list are the familiar “I will make you brooches” and “In the highlands” found towards the beginning of Songs of Travel. So what was “Aubade and Serenade”?

Beinecke ms. 6896 is similar to 6895 but contains a list of 19 items under the heading “Songs”, including all the titles in ms. 6895:

(An interesting puzzle for someone would be to work out what all the numerical calculations mean.)

In this longer list, “I will make you brooches” is again no. 8, and no. 9 is again “In the highlands.” Number 10 is “Let beauty awake.”

“Let Beauty Awake” is a two stanza poem in which the first is about the morning and the second about the evening. An aubade is a song for the morning while a serenade is for the evening.

So I conclude that item number 10 in both lists is the same and that “Aubade & Serenade” is “Let beauty awake.”

John F. Russell