Archive for the ‘Familiar Studies of Men and Books’ Category

Louis, Fanny and ‘Charles of Orleans’

When Stevenson first met Fanny Osbourne and fell in love he accepted an addition she suggested to his latest essay. Her contribution was first noted when preparing the essay for the upcoming New Edinburgh Edition of Stevenson’s Familiar Studies of Men and Books.

On 30 July 1876 Stevenson reported that his essay on ‘Charles of Orleans’ was finished and had been sent off to the Cornhill. The following month he left Edinburgh for London and then Antwerp where he was to begin his Inland Voyage river and canal journey on 25 August. In a letter to Colvin written just before leaving Edinburgh he still hadn’t heard from the Cornhill about the essay (Letters 2: 178, 181).

In the same letter to Colvin he said ‘I have an ultimate purpose of reaching Fontainebleau by water’, but he in fact ended at Pontoise, about about 17 km via the river Oise to the Seine below Paris. On 13 or 14 September he wrote to his mother from Pontoise mentioning ‘a bold, desperado sort of post card from my father; anent a proof of mine; which he has carefully violated as usual’ (Letters 2: 190). This can only refer to the ‘Charles of Orleans’ proofs. The same incident is alluded to at the end of An Inland Voyage, where he says a packet of letters picked up in Compiègne ended the holiday feeling and at their next stop, ‘a letter at Pontoise decided us’, and brought the trip to an end (Tusitala 17: 88, 110).

It is not clear whether it had been agreed that Thomas Stevenson would read the proofs when they arrived, or whether he took it upon himself to open the envelope: certainly, Stevenson did not welcome this interference, and two-and-a-half years later made sure his father did not see the proofs of Travels with a Donkey (Maixner: 64).

*

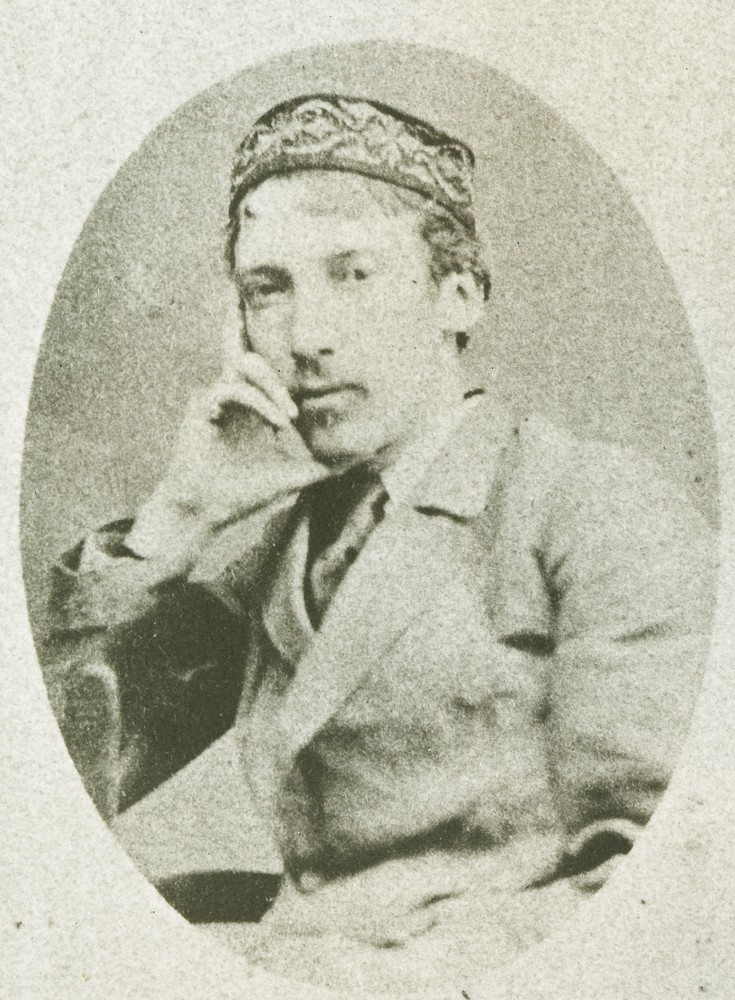

After Pontoise Stevenson and Simpson continued by rail to Paris and Grez, where they presumably arrived around 16 September—along with the two canoes (Lloyd Osbourne remembers them there). And there at the artist’s inn of Chez Chevillon, Stevenson met his future wife Fanny Osbourne. We have Lloyd Osbourne’s later recollection of Stevenson arriving, vaulting though the open window from the street and being greeted with delight by the company around the dinner table. Louis was attracted to Fanny first; Fanny, we know from her letters, was attracted to Bob Stevenson, but at a certain point he told her that his cousin was more worthy of her attention. (All this un-Victorian fluidity and freedom of relationships must have seemed like a new world to Louis.)

Anyway, they fell in love, ‘step for step, with a fluttered consciousness, like a pair of children venturing together into a dark room’, as Stevenson puts it in ‘Falling in Love’. Lloyd Osbourne remembers how Stevenson and his mother ‘would sit and talk interminably on either side of the dining-room stove while everybody else was out and busy, under vast white umbrellas, in the fields’ (Tusitala 17: xi).

*

One day, Stevenson must have given Fanny those proofs of his latest essay, ‘Charles of Orleans’ to read. The text published in the Cornhill in December of that year contains the following passage:

The reader will remember how Villon’s mother conceived of heaven and hell and took all her scanty stock of theology from the stained glass that threw its light upon her as she prayed. And there is scarcely a detail of external effect in the chronicles and romances of the time, but might have been borrowed at second hand from a piece of tapestry. It was a stage in the history of mankind which we may see paralleled, to some extent, in the first infant school, where the representations of lions and elephants alternate round the wall with moral verses and trite presentments of the lesser virtues. So that to live in a house of many pictures was tantamount, for the time, to a liberal education in itself.

After reading the essay, Fanny suggested the parallel between knowledge conveyed through images in the Middle Ages and the images in the classroom of the infant school, and Stevenson (always interested in parallels between primitive and infant psychology) must have inserted it on the proofs.

We know this because when the essay was collected in Familiar Studies in 1882, Stevenson, replying to a letter from Alexander Japp, said, ‘The elephant was my wife’s: so she is proportionately elate you should have have picked it out for praise’ (Letters 3: 310).

Stevenson and Bourget: an enigma

Why was RLS so enthusiastic about Sensations d’Italie?

Paul Bourget (1852–1935), French critic, essayist, novelist and poet, much appreciated in his own day, is not now widely known even in France. The publisher’s presentation of an introductory volume Avez-vous lu Paul Bourget? (2007) begins by saying that he is now ‘little known, even scorned’ (‘méconnu, voire méprisé’). Quite a downfall for a writer who was nominated for the Nobel prize no fewer than four times.

Stevenson’s reaction to Sensations d’Italie

Bourget’s friend Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Sensations d’Italie (1891), which he later described to Stevenson as ‘one of the most exquisite things of our time’ (Letters of Henry James, I, p. 188). Stevenson was enthusiastic—sent off immediately for all Bourget’s essays and at the same time wrote ‘I have gone crazy over Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (L7, 197, 205) and told James ‘I am delighted beyond expression by Bourget’s book; he has phrases which effect me almost like Montaigne’ and the following day told him, ‘I have just been breakfasting at Baiae and Brindisi, and this charm of Bourget hag-rides me. […] I have read no new book for years that gave me the same literary thrill as his Sensations d’Italie‘ (L7, 210–11) Not only this, but he looked forward to meeting Bourget on a planned trip to Europe and dedicated Across the Plains to him, the only one of his volumes not dedicated to a personal friend or family member.

You cannot step twice into the same book

Some years ago, inspired by such an impressive recommendation, I bought a second-hand copy of Sensations d’Italie, expecting it to be a cross between Montaigne and Proust and promising myself an exquisite reading experience. Unfortunately, what struck me then were the mentions of trains and inns and long appreciations of paintings. It did not resemble Stevenson’s own travel writing: there are no descriptions of his feelings or of the people he meets, no detached irony.

Why was Stevenson so enthusiastic? The best way to answer this question would be to look at his copy of the book with his scorings and approving underlinings. It is in the Fales Library of New York University on Washington Square in Manhattan—which unfortunately is closed because of the present pandemic emergency, and probably will be closed after that as closure for renovation was planned from May to September 2020.

Stevenson’s copy being unavailable, I decided to re-read the copy I had with a fresh eye, suppressing the expectations of the previous occasion.

Amazingly, this time I read a different book. I noticed the essayistic passages about art and artistry, the ethical, psychological and aesthetic passages and the embedded narratives with striking and memorable details. The uncomfortable trains and inns were still there, but this time they faded into the background.

What Stevenson may have appreciated

We cannot be certain about what Stevenson liked about Sensations d’Italie but we can make an educated guess, especially concerning aspects that might have found an echo in his own thinking. When Stevenson’s copy of Sensations d’Italie becomes available again, it will be interesting to see which of the following passages are marked. (Quotations are from the 1892 English translation, Impressions of Italy, with page references followed by page references of Sensations d’Italie.)

[March 2024: Stevenson’s copy has now been consulted (the results can be found here) and the following ‘educated guesses’ annotated according to the markings found there.

.

1. Affiinities with Montaigne

One clue from Stevenson’s letters on the book is his praise for ‘phrases which effect me almost like Montaigne’. I think perhaps he may be thinking here of Montaigne’s striking metaphors (such as that of the give and take of conversation being like playing tennis). Here is what seems a Montaigne-like metaphor:

1.1 In every work of art, whether it be a picture or a book, a statue or a piece of music, there is a hidden principle of life, that is to say, a secret virtuality unsuspected by the creator of the work. Have you ever seen a ropemaker at his work, walking backward without looking where he is going ? We are all, great and small, working like him, half consciously, half blindly, and above all we do not know what purpose our work will serve when it is finished. (126; SdI, 129–30)

[marked]

2. Affinities with Stevenson’s style:

2.1 Chapter 17 begins realistically with the ‘local train which moves almost like a steam tramway’ across ‘the vast plain of Apulia’ but then it changes register to the imaginative picturesque as Bourget’s destination reminds him of the story of how Manfred, last of the Hohenstaufen dynasty of Sicily, following defeat by Charles of Anjou and the revolt of his barons, sought refuge in Lucera ‘among his father’s Saracens’.

The story, too long to quote in full here, reminds me of Stevenson’s praise of ‘the poetry of circumstance’, ‘the fitness in events and places’, and ‘fit and striking incident’, ‘which stamps the story home like an illustration’ (in ‘A Gossip on Romance’). It has elements that are similar to the assassination of Archbishop Sharp that had long fascinated Stevenson and that he recounts in ‘The History of Fife’. In short, I hereby predict that when the volume in the Fales Library can be consulted again, the pages containing the story of Manfred’s flight (SdI, 179–82) will be approvingly marked in Stevenson’s hand.

Bourget says that the story is recorded by a chronicler ‘with a rare mixture of strength and simplicity’ (reminding me of Stevenson’s attraction to the prose of the Covenanters), it is a kind of passage that is ‘short, but which remain in the memory’ (‘si courtes mais qui restent dans l’esprit‘), like the ‘striking incident’ praised by Stevenson in ‘A Gossip on Romance’. Bourget then quotes the words of the chronicler:

He accordingly set out on a November night, accompanied by a scanty escort, to ride across this plain of Tavoliere to an asylum of which he was not even sure. The rain was falling. ‘It augmented,’ says Jamsilla, ‘the darkness of the night. The prince and his companions were unable to see one another. They could recognize each other only by the sound of the voice and by the touch. They did not even know whither the road they were following led, for they had ridden across the open country in order to throw possible pursuers off the scent.’ (175; SdI, 180–1)

After a bivouac overnight Manfred arrived at the walls of Lucera where ‘he was obliged to make himself known — an incident so romantic as to seem taken from a romance [trait si romanesque qu’il en semble romantique] — by his beautiful fair hair.’ The Moors had orders not to admit him, but said he could get round the order by entering through the sewer. Manfred prepared to do this and then (in the words of the chronicler) ‘This humiliation of the son of their beloved emperor awakened their remorse. They broke down the gates and Manfred entered in triumph.’

[this whole episode is marked]

2.2 The only clue from his letters as to what part of Bourget’s book he might have found fascinating is the comment, ‘I have just been breakfasting at Baiae and Brindisi, and this charm of Bourget hag-rides me’. It should be mentioned, however, that Bourget does not go near Baiae or Naples, so Stevenson has just introduced that name for the alliteration to suggest a large part of southern Italy. Brindisi, however, is there and is associated with a haunting impression:

by having heard, by hearing still, the clanking of the chains worn by the galley-slaves resounding through the castle on the seashore. I have seen many prisons and many abodes of misery, […], but nothing has pierced my heart like the sound of those chains, forever and forever accompanying my steps, as I walked through the courts and the halls of the fortress. […] The noise made by each one, walking with his heavy step, is slight ; but all these slight sounds of iron clanking against iron unite together in a sort of metallic roar, making the whole fortress vibrate. It is indistinct, mysterious, sinister’ (217–18; SdI, 222–3)

[not marked, though he does mark a vignette of contrasting misery and affection from the same prison (SdI, 224.6–13]

This reminds me of the haunting sound of the waves in Treasure Island and in other texts by Stevenson.

2.3 Perhaps too Stevenson appreciated impressionistic descriptions that reminded him of his writing in the 1870s, such as:

Little girls […] whisper and laugh together and shake their pretty heads, bright patches on the dark background of the church [taches clairs sur le fond obscur de l’église]. (74; SdI, 75)

[not marked]

.

3. Ethical concerns

3.1 Stevenson admired those who did what they thought was right and bravely faced the consequences, like the Covenanters and Yoshida-Torajiri, with his ‘stubborn superiority to defeat’, and Bourget provides us with another example of such a type. In ch. 21 he visits the castle of duke Sigismondo Castromediano: a ‘deserted manor’ where everything shows ‘a strange abandonment’, yet inhabited by the eighty-year old Duke who

has suffered all the tortures of a proscription as cruel as that of the companions of the Stuart conspirator. He threw himself, heart and soul, into the movement against the Bourbons of Naples, after the events of 1848. Arrested and condemned to death, his sentence was commuted to imprisonment for life in the galleys, and, refusing to sue for pardon, he was for eleven years a galley-slave. (241; SdI, 246)

Eventually he escaped to England and returned at the time of Garibaldi. The castle ‘he has left untouched whether from a stoical indifference in regard to the comforts of life, acquired in misfortune, or from pride in his sufferings’ (242; SdI, 247).

[not marked]

.

4. Psychological concerns

4.1 From about 1880 Stevenson was increasingly interested in how we can understand the world-view of people from very different cultural traditions, and we find this too in Bourget:

[the myths of the ancients:] the human feeling which underlies their religious ideal makes it possible for us to have communion with them, in spite of the differences of creeds and customs. (92; SdI, 95)

[not marked, but see the related next item]

4.2 In two essays written in 1887 ‘Pastoral’ and ‘The Manse’, Stevenson speculates on inherited primitive memories and how his ancestors are a part of him and he found some similar thoughts in Bourget:

the innumerable threads which heredity inextricably weaves into our being, so that in the sincere Christians of to-day their pagan ancestors, and other ancestors of still darker beliefs, live again (273; SdI, 279).

[not marked, but a related idea about pagan survivals is (SdI, 196.18–197.8)]

4.3 The following passage has various echoes in Stevenson’s idea of constant variation in identity;

[T]he varying complexity of the I [la complexité changeante du moi] (56–7; SdI, 58)

[not marked]

4.4 In Bourget, Stevenson would have found ideas that were close to his own about the moral nature of the artist, about ‘the sympathetic interpretation of feeling’, and about the hidden feelings and motives that he explores in ‘The Lantern Bearers’:

talent has always, and without exception, a close resemblance to the moral nature of the individual. I mean a certain sort of talent; that which consists neither in facility of execution, nor a profound knowledge of effects, but in a sympathetic interpretation of feeling. The facts of a man’s life are so little significant of his real nature! The likeness of us which our actions stamp on the imagination of others is so deceptive! Do others, even, ever thoroughly understand our actions, and if they understand them are they able to unravel their hidden motives? Do we confide to others the world of thoughts that has stirred within us since we have come into existence: our inmost feelings, the secret tragedy of our hopes and our sorrows, the pangs of wounded self-love, the disappointment of ideals overthrown? (45; SdI, 46)

[marked, and the sentence on ‘The facts of a man’s life’ is underlined]

4.5 Neither the doctrines of these believers nor their prejudices concern us any longer; it is their I — like ours in its secret needs, but which possessed what we so greatly desire — yes, it is this pious and heroic I which kindles our fervor from the depths of the impenetrable abyss into which it has returned. (140; SdI, 143–4)

[not marked]

5. Thoughts on art and aesthetics

Finally, Stevenson was interested not only in theories of narrative and in technique and style but also in the philosophy of art, the nature of artistic genius, common elements of all the arts, the relationship between the artist and the finished work, the elusive charm of the artistic experience. Bourget too was interested in these aesthetic questions and in his book Stevenson would have found a writer with whom he could engage in an exchange of ideas.

5.1 ‘Why, recognizing in every human action something of unconsciousness and of destiny, should we not admit that the genius of the great artists was greater than they themselves knew?’ (53; SdI, 53)

[not marked, but a similar idea is marked (Sens, pp. 129.12–132.4)]

5.2 Is the purpose of literature, then — I mean literature which is worthy of the name — different from that of the other arts — music and architecture, sculpture and painting ? Like them, and in a language of its own, what does it express but shades of human feeling? (130; SdI, 133–4)

[marked]

5.3 The supreme gift reveals itself in them [artists of genius], as it does wherever it is met with, by the master virtue, unerring clearness of vision. (137; SdI, 140–1)

[not marked]

5.4 This word [charm], so vague in its signification, […] is the only one which expresses the magic of certain […] works, shadowy, incomplete, […] but by which one feels one’s self loved as by a person, and which one loves in the same way. There are two classes of artists who have always shared between them the dominion of the world: those who depict objects, effacing themselves altogether ; and those whose works serve chiefly as a pretext to lay bare their own hearts. It is in vain that I admire the former with my whole strength and tell myself that they will never deceive me, while the sincerity of the others is often doubtful and they may always be suspected of posing — my sympathies go with the latter, it is with them I like to be. (117–18; SdI, 120–1)

[marked; the final passage beginning ‘There are two classes of artist’ has a double marginal line]

5.5 a book […] is not entirely the same a hundred years after it has been written. The words are unchanged, but do they preserve exactly the same signification ? What reader of intellectual tastes does not understand that for a man of the seventeenth century Racine’s poetry was not what it has become for us ? (127; SdI, 130)

[marked]

RLS on his father

Father and son relationships are often difficult, and the Stevenson family was no exception. For an idea of how this may have influenced RLS’s writings we need only think of the overbearing father figures in his fiction.

An interesting document in this regard is the record of his father’s ‘faculties’ (bodily and mental characteristics and aspects of personality) in the copy of Galton’s Records of Family Faculties in the library at Vailima and now at Yale, reproduced in Julia Reid’s Robert Louis Stevenson, Science and the Fin de Siècle:

Reid says this is ‘in Fanny’s hand’ but it seems clear to me that it is by Stevenson himself. Take the word ‘dark’:

and compare it with the same word in ‘Memoirs of Himself’ written in 1880:

Here we see the very typical R-shaped ‘k’ and the inverted-v ”r’. Other typical features (not shown here) are the lead-in line to the ‘f’ rising to a spur and the same in the case of the ‘b’ but the ‘p’ starting with a hook. Having studied Stevenson’s handwriting for some time, my opinion is that this is written by him not Fanny. This only makes the entry more interesting.

An interesting description

The description of ‘Character and temperament’ begins ‘choleric, hasty, frank, shifty‘. The adjective ‘hasty’ must be used in the sense of ‘quickly roused to anger; quick-tempered, irritable’ (OED). It is interesting that we find the same adjective applied to a father in Kidnapped

his gillies trembled and crouched away from him like children before a hasty father.

Kidnapped, ch. 23

Hastie is the first name of the white-haired Dr Lanyon in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and he is quick tempered in his outbursts against Jekyll (‘scientific balderdash’, ‘I am quite done with that person’), a habit of thoughtless and absolute rejection that makes him similar to Jekyll (who uses the same words as Lanyon when he twice repeats that he is ‘done with’ Hyde).

The last adjective is ‘shifty’. I don’t think that can mean ‘dishonest, not to be depended on’ etc. There’s no entry for the word in the Dictionary of the Scots Language but I can imagine it had a special use north of the border from two OED citations:

1859 […] The canny, shifty, far-seeing Scot

1888 W. Black [writer of the kaleyard school] In Far Lochaber xxiii She was in many ways a shifty and business-like young person

So it could have the positive meaning of ‘well able to shift for oneself’. But context is very important in determining meaning and here the other three adjectives are about the quality of interactions with others rather than such a practical ability, so perhaps we should search further. Some help comes from Stevenson’s use of the word in his essay on John Knox:

He was vehement in affection, as in doctrine. I will not deny that there may have been, along with his vehemence, something shifty, and for the moment only; that, like many men, and many Scotchmen, he saw the world and his own heart, not so much under any very steady, equable light, as by extreme flashes of passion, true for the moment, but not true in the long run.

Here ‘something shifty, and for the moment’ is associated with ‘vehemence’ and ‘passion’. It looks like a ‘shifty’ person is someone who changes position and beliefs as his passions dictate. Could this be the authoritarian person who can quickly justify any action?

Some more evidence of Stevenson’s use of the word is found in Weir of Hermiston (ch. 2), where the elder Kirstie has only the company of the maidservant

who, being but a lassie and entirely at her mercy, must submit to the shifty weather of “the mistress’s” moods without complaint, and be willing to take buffets or caresses according to the temper of the hour.

Here ‘shifty’ is associated with the changeable and unpredictable moods of an authoritarian person and this might fit Thomas Stevenson better.

Finally, in the company of the other three adjectives ‘frank’ probably doesn’t mean ‘open, sincere’ but more ‘candid, outspoken, unreserved’.

The Stevenson Manuscripts Collection at Harry Ransom Center

The launch (on 30 June 2015) of a new online resource of manuscript images by the Harry H. Ransom Center (HRC) in the University of Texas at Austin, provides an outstanding resource for scholars and is a welcome policy of access to out-of-copyright materials. Even the HRC, a centre of expertise in this area, has to say ‘manuscripts … believed to be in the public domain’—so complicated and unknowable are the laws of copyright. Hence this new policy of is all the more welcome to those of us who know somewhat less about it all.

.

.

.

The “Robert Louis Stevenson Collection” contains images and information of all the HRC’s 48 Stevenson and Stevenson-related MSS. By clicking the link Browse all items in the collection, you will see them all listed and with links to images.

Immediately we see another benefit of the new resource: it makes the wealth of resources of the HRC more visible, less easy to miss. If we choose to browse the 12 Works by RLS, we see it contains for the most part interesting MSS of works already published that will be of great interest to our Edition, and previously classed as ‘untraced’. I personally did not know of the location here of any of these MSS before opening the page yesterday and seeing fascinating list of titles and thumbnail images. Nor are any of them listed as located here in Roger Swearingen’s The Prose Writings of Robert Louis Stevenson (1980).

The 13 Letters from RLS are all in the Yale Letters, identified as ‘MS Texas’ (unless they have recently changed hands), so all merit to Ernest Mehew for finding this part of the Collection. Having these items so conveniently available will be of a help if we have to use handwriting to date another MS.

The 23 Miscellaneous items contain many things of interest, including music, an early list of favourite books, University lecture cards, receipts for payments and letters about RLS.

It is amazing that much of this remained both ‘known’ as in some way available and ‘unknown’ because not found by anyone interested in it. And it is not the case that these items were only recently acquired.

The MS of one of Stevenson’s most witty essays ‘The Ideal House’, sold in 1914, and of ‘Virginibus Puerisque’ and ‘On Falling in Love’, sold in 1918 to raise funds for the British Red Cross, were considered ‘untraced’—until yesterday. Yet they were part of the collection of eccentic bibliophile T. Edward Hanley (1893-1969), whose collection was acquired by the University of Texas in 1958 and 1964, and therefore have presumably have been catalogued there for over fifty years. The MS of ‘A Winter’s Walk in Carrick and Galloway’, which no-one has even located in a sale catalogue, was in the John Henry Wrenn collection, purchased by Library as long ago as 1918, so has been here for almost a century.

‘Talk and Talkers’ MS (again, not located in any sale catalogue so far) was transferred to the Ransom Center in 1960 from the University of Texas Rare Book Library. The leaf frm the Notebook draft of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, sold in 1914, was received in the Manuscripts department, again internally transferred, in 1974.

Hats off then to the Harry Ransom Center and the REVEAL team for providing not only an unparalleled resource but also a network of references that has allowed its items to be discovered.

Essay on Hugo with an addition by Colvin

One of RLS’s most impressive early essays is that on Victor Hugo’s novels (later included in Familiar Studies of Men and Books). He finished the fair copy at Swanston on 4 May 1874 and sent it to Colvin for his opinion. This was returned with some changes and on 4 June RLS writes to him:

“Victor Hugo” has come; I like all your alterations vastly, except one which I don’t like, tho’ I own something was needed there also.’ (L2: 18)

Not many early MSS of RLS survive, but luckily this is one of them (Yale GM664-63-1453, if I may invent an abbreviation). In a note to the above letter, Mehew identifies one change by Colvin (on f. 40) that, not deleted in the MS, was removed in proof:

Having thus learned to subordinate

his story to an idea to make his art

speak <ins>both to the artistic and the moral sense, and at best to both these harmoni:/ously together</ins>, he went on to teach it to say

things heretofore unaccustomed. […]

In the insertion, the three b’s with a loop stand out immediately as not typical of RLS’s handwriting. The lead-in line to RLS’s b sweeps up to a point or spike, in contrast his h always attempts to start with a loop – indeed, we have taken the absence/presence of a loop as a way of disambiguating between b and h. Look at the bs and h’s in the lines immediately below in the same MS:

The insertion also has another unusual feature: ‘harmoniously’ ends with a gamma-y; while RLS (as far as I can remember) writes ‘y’ like a tailed-u (as in ‘say’ below the word), or uses yough-y (French-y, as in ‘hastily’ in the second picture). The use of a colon instead of a hyphen (‘harmoni:’) is also unusual.

(There is one small hitch: in the reproduction that addition looks as if it is in the same ink as the rest of the writing, clearly an impossibility – but a check of the MS should decide the matter. I also need to acquire a better knowledge of the handwriting of Colvin (so I can see what other changes in the MS Colvin suggested) – for the moment, we can rely on the testimony of Mehew, who was familiar with all the hands connected with RLS MSS.)

I ought to add that Colvin’s possible changes in the MS seem examples of helpful collaboration rather the imposition of a different point-of-view. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the episode is that RLS in 1874 was already confident enough to reject the rather weak and inconsequential addition by Colvin in the example above.

Talks by the EdRLS Essay Editors

The Literary 1880s: James, Stevenson and the Literary Essay

As part of the Literary 1880s workshops, the editors of the new EdRLS edition of Stevenson’s essays were invited to present aspects of their work on 23rd March 2012, in the Conference Room of David Hume Tower, in the University of Edinburgh.

*

James and Beerbohm

James and Beerbohm

First, we heard from two people on other 1880s essay topics. Workshop-organizer Andy Taylor explored the changing position of Henry James in his 1883 essay on Trollope. This enters the 1880s area of debate over Realism, French Naturalism, and the art of fiction to which RLS made important contributions in essays such as “A Note on Realism” and “A Humble Remonstrance”, but the focus here was on James’s shifting attitude to Trollope and his position in the cultural rivalries of Britian and the USA.

Then Sara Lodge talked on Max Beerbohm and “camp aesthetics”, in which she made many points of interest to our exploration of Stevenson’s essays, starting with her thoughts about the essay as a literary genre, identifying it as a performative form associated with the creation of a persona, and so related to the dramatic monologue.

Then Sara Lodge talked on Max Beerbohm and “camp aesthetics”, in which she made many points of interest to our exploration of Stevenson’s essays, starting with her thoughts about the essay as a literary genre, identifying it as a performative form associated with the creation of a persona, and so related to the dramatic monologue.

This she saw as developing from the 1820s onwards, citing Lamb and Hazlitt — though my view of Stevenson’s essays is that he revives this tradition after it had disappeared under the oratorical and earnest emphatic style of the mid-Victorian monthly magazines. So in what way was the obvious “performance” of the high-Victorian sages different from that of Lamb, Hazlitt and Stevenson? Perhaps readers of this blog would like to comment.

The essay, Sara continued, is also like a confession — and here she referred to Adam Phillips, who the essay editors had seen speaking on this very subject (the affinities of the essay with the psychoanalytic narrative) at the Literary Essay conference at Queen Mary in London a few months before.

In any case, the essayist keeps a distance between the apparent and the real object of the writing, and this can be seen as either deliberate and artful, or unintended. The same can be said of performing in general: we are always performing, but we don’t realize it most of the time. One form of very self-aware performance, is “camp” behaviour.

(Sara sees the origin of “camp” in a distancing from aestheticism and as being created by Wilde. I feel that, although “camp” as “homosexual codes of signifying behaviour” is very probably modelled on Wilde, it has, however, a wider and non-homosexual meaning, deriving, as Susan Sontag suggests, from “the eighteeth-century pleasure of over-refinement”. Stevenson’s New Arabian Nights can be seen as a camp text, and was written in the 1870s before Wilde appeared on the London scene, and the reported behaviour and the discourse of RLS, Bob and Simpson also have, to me, clear campish aspects.)

Sara then illustrated self-mocking camp “failed seriousness”, the celebration of the absurdity of things, in the early essays of Beerbohm, such as “1880” and “An Infamous Brigade”.

***

The Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert-Louis Abrahamson opened the session on Stevenson’s essays with an overview of Stevenson’s career as an essayist. He made the point that the 1879-80 journey to California was not an immediate turning point. His essay-writing career falls into two main periods 1874-82 (with one essay in 1873) and 1883-88 (with one final essay in 1894).

His first essays were aesthetic, to fit their destination, the fine-art magazine Portfolio; and a focus on the visual arts also marked his group of essays for Henley’s Magazine of Art in the early 80s. Sidney Colvin steered him away from heavy subjects (the essays on Knox and Savonarola he had planned), seeing him as an irreverent ally in the Darwinian cultural wars. He also introduced him to Leslie Stephen’s Cornhill Magazine, which became his “home” for twenty essays in the first part of his career, including most of those collected in Virgninibus Puerisque in 1881 and in Familiar Studies in 1882.

The magazine associated with later part of his career was the New York Scribner’s, where he published thirteen essays, including the monthly series published in 1888. These twelve essays have, strangely, never been published together in a sequence before, but will be so in our edition.

Alex Thomson then talked about Memories and Portraits (1887), the collection of essays that he is editing, characterizing it as an “Edinburgh book”, significantly placed in 1894 in volume 1 of the Edinburgh Edition, together with Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes.

Alex Thomson then talked about Memories and Portraits (1887), the collection of essays that he is editing, characterizing it as an “Edinburgh book”, significantly placed in 1894 in volume 1 of the Edinburgh Edition, together with Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes.

The “Memories” of the title can be seen in the context of a Scottish tradition of “reminiscences” (for example, Ramsay’s Reminiscences of Sottish Life and Character) and of commemoration, linked to the desire to preserve the memory of a disappearing culture. The “Talk and Talkers” essays can also be seen in a Scottish Enlightenment tradition of conversation and sociability. “Portraits”, on the other hand, suggests more a London-based tradition of aestheticism (e.g. Pater’s Imaginary Portraits).

Examples were given of the changes between 1871 and 1887 in “An Old Scotch Gardener”, showing how Stevenson mostly deleted, allowing anecdotes to stand on their own without the earlier chatty interpretation.

These essays are self-reflexive (both about memories and the reflecting subject, as RLS admits in the prefatory “Note”), and so have interesting affinities to the romantic lyric poem. They also reveal a subject that is both detached from his culture, attracted to a wider cultural context outside Scotland, distrustful of nostalgia, yet desiring to get back into contact with his own cultural identity (a quandary suggested by the key concept of “the foreigner at home”).

Richard Dury: I talked on style and its important persuasive and relation-creating function in the personal essay. An indication of its prominence is the way commentators illustrating Stevenson’s style in general have taken most of their quotations from the essays. His was a new voice in the 1870s, a reviver of Montaigne’s scepticism and an essayist who broke with high Victorian seriousness and emphasis.

Richard Dury: I talked on style and its important persuasive and relation-creating function in the personal essay. An indication of its prominence is the way commentators illustrating Stevenson’s style in general have taken most of their quotations from the essays. His was a new voice in the 1870s, a reviver of Montaigne’s scepticism and an essayist who broke with high Victorian seriousness and emphasis.

I then went on to charactize Stevenson’s essay style through six broad characteristics: lightness, enthusiasm, variousness, playfulness, strangeness and “charm” — used merely as tools to understand an elusive and mobile set of features, and as a way to understand why reading these essays is a source of pleasure.

The playful, complex and unexpected linguistic form of Stevenson’s essays can be seen in terms of Stevenson’s own concept of the “knot”: a slight delay in understanding, and also an interweaving of strands. This form is interwoven with an equally fascinating play of thought, both of them working together in the exploration of a world that has no centre or essence, where language is mobile and malleable. The effect of “a lot going on” in form and meaning is to make the reader more aware of text as performance and reading as an event in time. Stevenson’s essays are works of great value in themseves: elusive, fascinating and memorable reading experiences.

Lesley Graham ended the afternoon with an overview of the history of the reception of the essays. Often appreciated above all as a brilliant essayist in his lifetime, in the early years of the twentieth century the essays were quarried for quotations (collected in slim self-help volumes), especially those emphasising on happiness and friendship and the importance of courage to face the struggle of life. These very aphorisms were then used to condemn the essays after the First World War.

Lesley Graham ended the afternoon with an overview of the history of the reception of the essays. Often appreciated above all as a brilliant essayist in his lifetime, in the early years of the twentieth century the essays were quarried for quotations (collected in slim self-help volumes), especially those emphasising on happiness and friendship and the importance of courage to face the struggle of life. These very aphorisms were then used to condemn the essays after the First World War.

In the USA, where the teaching of literature was associated with the teaching of writing, essays were a privileged genre and Stevenson’s widely used as models. Then, however, there was a turn away from the literary essay in both Britain and the USA, “the death of the essay”, reinforcing Stevenson’s general decline in critical favour.

With perhaps the single exception of Furnas in 1951, critics then continued to mainly criticize and downplay Stevenson’s essays, including Daiches in 1947 and Saposnik in 1974. A significant moment of change comes in 1988, a year which saw the publication of three anthologies of Stevenson’s essays by Treglown, and (in translation) Le Bris and Almansi.