Archive for the ‘Book dedications’ Category

Paul Bourget writes to Stevenson

A post contributed by Katherine Ashley

In 1891, Henry James sent Stevenson a copy of Paul Bourget’s Sensations d’Italie (1891). The book gave Stevenson a ‘literal thrill’ and he quickly requested more of his works. Bourget (1852-1935) was a poet, novelist, and playwright, but today he is mainly read by literary historians for his astute study of fin de siècle cultural malaise, Essais de psychologie contemporaine (1885). He was also, like Stevenson, a traveller, and it is fitting that Stevenson’s introduction to him was via Sensations d’Italie, a book about Bourget’s travels in Tuscany, Umbria and Puglia.

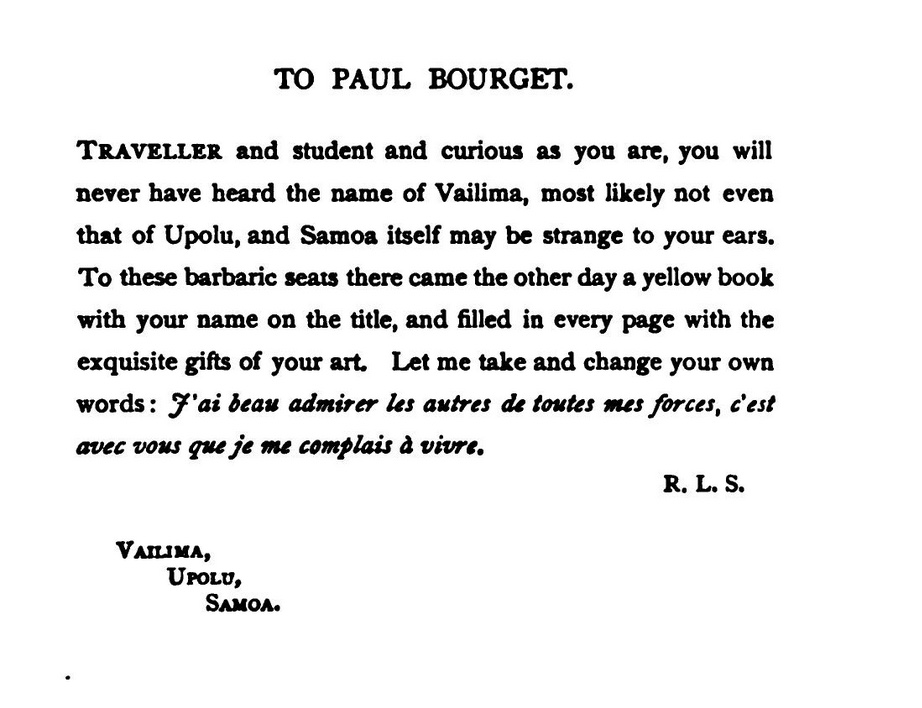

The reasons for Stevenson’s enthusiasm for Sensations d’Italie are explored in an earlier post; a direct result of his reading is that he dedicated Across the Plains (1892) to Bourget.

To Stevenson’s consternation, Bourget did not immediately respond to the compliment. He complained to Sidney Colvin: ‘ain’t it manners in France to acknowledge a dedication? I have never heard a word from le Sieur Bourget, drat his impudence!’. He was even more to the point in a letter to James. Although the tone is good-humoured, there is an element of hurt and annoyance:

I thought Bourget was a friend of yours? And I thought the French were a polite race? He has taken my dedication with a stately silence that has surprised me into apoplexy. Did I go and dedicate my book to the nasty alien, and the ’n’orrid Frenchman, and the Bloody Furrineer? Well, I wouldn’t do it again; and unless his case is susceptible of Explanation, you might perhaps tell him so over the walnuts and the wine, by way of speeding the gay hours. Seriously, I thought my dedication worth a letter.

As it turns out, Bourget’s case was indeed ‘susceptible of Explanation’: work had prevented him from replying. The excuse seems reasonable, since Bourget spent the first months of 1892 in Rome, which resulted in his novel Cosmopolis (1893). He also published two other books around this time, La Terre promise (1892) and Un scrupule (1893).

Bourget’s contrite reply finally came, enclosed in James’s next letter to Stevenson. The manuscript is kept at Harvard University. It is transcribed and translated here.

Londres, le 3 août 93

Monsieur et cher confrère,

Je suis si coupablement en retard avec vous pour vous remercier de la dédicace du beau livre en tête duquel vous avez mis mon nom que je n’en finirais pas de m’en excuser. Le démon de la procrastination—ce mauvais génie de tous les imaginatifs—m’a joué des tours cruels dans ma vie. Il aurait commis le pire de ses méfaits s’il m’avait privé de la précieuse sympathie dont témoignait votre envoi—et venant de l’admirable artiste que vous êtes, cette sympathie m’avait tant touché. Peut-être trouverez-vous le mot de cette énigme de paresse dans une existence qui six mois durant, l’année dernière, a été celle d’un manœuvre littéraire esclavagé par un engagement imprudent—ce qui n’est rien lorsqu’on a le travail // facile, ce qui est beaucoup quand on ne peut pas « faire consciencieusement mauvais » comme disait je ne sais plus qui.

J’aurais voulu aussi, en vous remerciant, vous dire combien j’aime votre faculté et vision psychologique et comme il m’amuse en vous lisant de trouver entre ce que vous exprimez et ce que je sens sur des points analogues de singulières ressemblances d’âme. Croyez que, malgré mon silence, cette fraternité intellectuelle fait de vous un ami éloigné auquel je pense souvent. Je me réjouis de savoir par Henry James que vous avez retrouvé la santé sous le ciel où vous êtes réfugié. Que je voudrais pouvoir espérer qu’un jour nous nous rencontrerons, et que nous pourrons de vive // voix échanger quelques idées et parler des choses que nous aimons également ! Mais vous avez vraiment choisi l’asile presque inaccessible et je songe avec mélancolie que j’ai failli, voici des années, aller frapper à votre porte à Bournemouth. C’était un peu après vous avoir connu intellectuellement, et un autre démon, celui de la défiance, qui fait qu’on recule devant les rencontres les plus désirées, m’en a empêché. Voilà, Monsieur, beaucoup de diableries dans un petit billet qui devrait être toute chaleur et toute joie puisqu’il me permet de vous prouver ma gratitude d’esprit. Recevez-le comme une poignée de main bien sincère et croyez moi votre vrai et dévoué ami d’esprit.

Paul Bourget

Transcription: Katherine Ashley, Antoine Compagnon and Richard Dury

.

London, 3 August 1893

My dear fellow,

I am so shamefully late in thanking you for the dedication to the fine book at the front of which you put my name, that I’ll never be done asking for forgiveness. The demon of procrastination—that evil genie of all creative people—has played cruel tricks in my life. He will have perpetrated his worst mischief if he has deprived me of the precious sympathy demonstrated by your dedication—and coming from the admirable artist that you are, this sympathy has touched me greatly. Perhaps you’ll find an explanation for my mysterious slowness in an existence that for six long months last year was that of literary labour enslaved by unwise commitment—which is nothing when the work comes // easily, but which is much when one cannot ‘in good conscience do bad work’, as someone whose name escapes me once said.

In thanking you, I’d also like to tell you how much I appreciate your abilities and psychological vision, and how it amuses me, when reading you, to find a singular likeness of temperament between what you express and what I feel on analogous points. Know that, despite my silence, this intellectual fraternity makes of you a distant friend of whom I often think. I’m delighted to learn from Henry James that you have regained your health under the skies where you have taken refuge. How I’d like to hope that we’ll meet one day, and that we’ll be able to exchange ideas in // person and speak of things that we both love equally. But you’ve truly chosen an almost inaccessible sanctuary, and I think with wistfulness that years ago I almost knocked on your door in Bournemouth. It was shortly after getting to know you intellectually, and I was prevented by another demon, the demon of no-confidence that makes us back away from the most desired encounters. That, sir, is a lot of devilry for a short note that ought to be all warmth and pleasure, since it allows me to show my gratefulness. Please accept it as a sincere handshake indeed and consider me your true and devoted like-minded friend.

Paul Bourget

Translation: Katherine Ashley

.

See also the former post on Katherine Ashley’s recent study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature

.

.

.

.

.

.

Dedications to Stevenson

After the post on ‘Stevenson’s dedications to others‘, here are the printed dedications by other to him. These trace a network of friendships and give an idea of his growing repute, while several of them allude to friendship (as in Stevenson’s dedications) and to shared Scottish sentiments. They were appreciated by the recipient; referring to the first from Symonds and Low’s proposed dedication, Stevenson wrote to Low: ‘It is a compliment I value much; I don’t know any that I should prefer’ (L5, 87).

- The first book dedicated to Stevenson was by John Addington Symonds, a friend of many conversations at Davos in the winters of 1880–81 and 1881–2, in his Wine, Women, and Song: Mediæval Latin Students’ Songs (London: Chatto & Windus, 1884). It’s in the form of the letter to a friend, a kind of dedication that if not invented by Stevenson, was developed and popularized by him:

2. The following year brought the a dedication to Stevenson from someone not personally known to him (though they had mutual friends), an American couple who had moved to London: the illustrator Joseph Pennell and his wife the writer Elizabeth Robins Pennell. They dedicated their illustrated account of journey from London to Canterbury on a tandem tricycle: A Canterbury Pilgrimage, ridden, written and illustrated by Joseph and Elizabeth Robins Pennell (London: Seeley, 1885). It is an inscription with something of Stevenson’s charm and graceful phrasing:

(For Stevenson’s letter of thanks, see L5, 121–2.)

3. Another admirer unknown to Stevenson personally was Joseph Gleeson White who dedicated to him his Ballades and Rondeaus, Chants Royal, Sestinas, Villanelles, &c. (London: Walter Scott, 1887). This takes the form of a brief inscription followed by a message, not fully in the form of a letter, but with address directly to Stevenson:

(For Stevenson’s thoughts on whether he deserved such praise, See L5, 370.)

4. The following year Will Low, an old and close friend, dedicated to Stevenson his illustrated edition of Keats’ Lamia (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1888) within an illustration:

On the thin scroll above the top border is a quotation in Latin from Cicero ‘There is no more sure tie between friends than when they are united in their objects and wishes’. The text of the dedication displayed by an amoretto is: IN TESTIMONY OF LOYAL FRIEND- / SHIP AND OF A COMMON FAITH IN / DOVBTFVL TALES FROM FAERY LAND, / I DEDICATE TO / ROBERT LOVIS STEVENSON / MY WORK IN THIS BOOK : WHL

The use of ‘doubtful’ to mean (probably) ‘open to many interpretations’ (a meaning not found in the OED) is influenced by a use of French douteux; it imitates Stevenson’s own use of epithets and Gallicisms, creating new meaning through the context of use.

In Stevenson’s copy, sold 1914 (now at Brown University) Low, in 1928, added a long note to the flyleaf, in which he says it was

a book which held for Stevenson and myself more than the text, more than the drawings, would imply. The common faith “in doubtful tales from fairyland”, was more than a form of words it was the basis of our friendship.

Stevenson wrote to Low thanking him for ‘the handsome and apt words of the dedication (L5, 62–3) and sent him a poem in thanks (‘Youth now flees on feathered foot’, L5, 164)

5. The same year brought a dedication on a work of visual art, the gilded copper plaque by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Robert Louis Stevenson, in the first version (1888):

The panel includes Stevenson’s poem ‘To Will H. Low’ above Stevenson’s lifted hand holding a pencil, and in the top right-hand corner the dedication: TO ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON / FROM HIS FRIEND AUGUSTUS / SAINT-GAUDENS. The bond of friendship (here, between three friends) is again specifically mentioned, as in many of Stevenson’s own dedications to others.

6. In 1891 Marcel Schwob dedicated to him his Cœur double (Paris: Ollendorff) with the the simple inscription: A / ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON. But in the presentation copy he sent to Stevenson he added the following in English below:

To Robert Louis Stevenson this book is dedicated in admiration of ‘Treasure Island’, ‘Kidnapped’, ‘The Master of Ballantrae’, in the name of the new shape he has given to the romance, for the sake of our dear Francis Villon — Marcel Schwob.

7. In 1892 the critic George Saintsbury, fellow Savile Club member, dedicated to Stevenson his edition of The Essays of Montaigne Done into English by John Florio (London: David Nutt), with another simple inscription:

The ‘contrivers’ included W. E. Henley, general editor of The Tudor Translations series of which this was one. Henley’s original idea had been to dedicate it to ‘To the R.L.S. of Virginibus Puerisque, Memories & Portraits, Across the Plains’ (letter to Baxter, 4 May 1892; Yale, B 4633), associating the volume of Montaigne specifically with Stevenson the essayist (possibly also intended as the early Stevenson, from in the period when they had both been close friends). Perhaps Saintsbury, the austere critic, did not approve the association of Stevenson the essayist with the acknowledged master of the genre; for whatever reason, the resultant dedication seems strangely unbalanced.

8. The same year Alan Walters dedicated to Stevenson his Palms & Pearls; or: Scenes in Ceylon (London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1892). Walters, clearly trying too hard, produced an elaborate classical-style inscription:

9. A classical inscription, but in contrast concise and densely poetic, was also chosen by S. R. Crockett for his dedication to The Stickit Minister (London: Fisher Unwin, 1893):

Stevenson was touched by this evocation of the hills of Galloway (seen on his ‘Winter’s Walk’ in January 1876), while ‘the graves of the martyrs’ made him think instead of Allermuir close to Swanston (familiar from his student days and through his early career) (L8, 159, 193–4). It inspired him to write a poem (later included in the posthumous Songs of Travel of 1895) and include it in the letter of thanks to Crocket (L8, 152–4). The first of the three stanzas is: ‘Blows the wind today, and the sun and the rain are flying, / Blows the wind on the moors today and now, / Where about the graves of the martyrs the whaups are crying, / My heart remembers how!’ The last line of this first stanza then inspired Crocket to change the last line of his dedication in future editions so that it echoed Stevenson’s poem:

In addition to the changed last line to the Dedication, the ‘second edition’ (1894) has a ‘Letter Declaratory’ beginning ‘Dear Louis Stevenson’ modeled on Stevenson’s own elegant dedicatory letters, preceded, on the page facing the dedication, by a facsimile of Stevenson’s MS poem and a transcription of it .

10. The last dedication to Stevenson was a dedicatory poem in Scots by his friend Andrew Lang in The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies, ed. by Robert Kirk and Andrew Lang (London: David Nutt, 1893). This addresses ‘Louis’ in a far land where the inhabitants know nothing of Scottish religion (self-mockingly presented) but have many supernatural tales, and encourages him to tell them Scottish supernatural tales, which ‘stamped wi’ TUSITALA’S name / They’ll a’ receive them’ and ends with the world-weary poet wishing himself to be taken away by the fairies. Here is the first of the seven verses: