Stevenson in Homburg, 1862

Stevenson visited Germany on four occasions: 1. Homburg (now Bad Homburg vor der Höhe) with his parents, July—August 1862; 2. The following year travelling home from Italy with his parents (Munich—Augsburg—Nuremberg—Frankfurt—Cologne) in May 1863; 3. Frankfurt during his first summer vacation as a student with Walter Simpson, July—August 1872; 4. And finally, for a few days, joining his parents at Wiesbaden in September 1875.

Although steeped in French culture, Stevenson was also attracted to German thought and literature.The 1872 stay in Frankfurt was to improve his German. After the death of his friend James Walter Ferrier, Stevenson remembered that Ferrier, probably in the early 1870s, ‘had [=? had made] a pretty full translation of Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters, which we read together, as well as the second part of Goethe’s Faust, […] he helping me with the German’ (Letters 4: 206). He quotes Goethe and Heine in German several times in his letters from 1872 to 1875 (Letters 1: 289, 316, 403; Letters 2: 13, 72, 81, 122) and read Heine’s love poems together with Fanny Sitwell in the summer of 1873 (Letters 2: 31).

His German experiences are reflected in ‘Will O’ the Mill’ (1878) and Prince Otto (1885) as well as an abandoned essay on Homburg, ‘An Onlooker in Hell’, for a series, planned in 1890, to be called ‘Random Memories’. This latter is now in the NLS (MS 3112, ff. 308-311) and will be published in our Essays V, presently being prepared by Lesley Graham

But to return to his first experience of Germany, not yet twelve years old, in the summer of 1862. A reader of this blog, Thomas Obst, lives a few miles from Bad Homburg and, after some local research, kindly supplies the following facts and images.

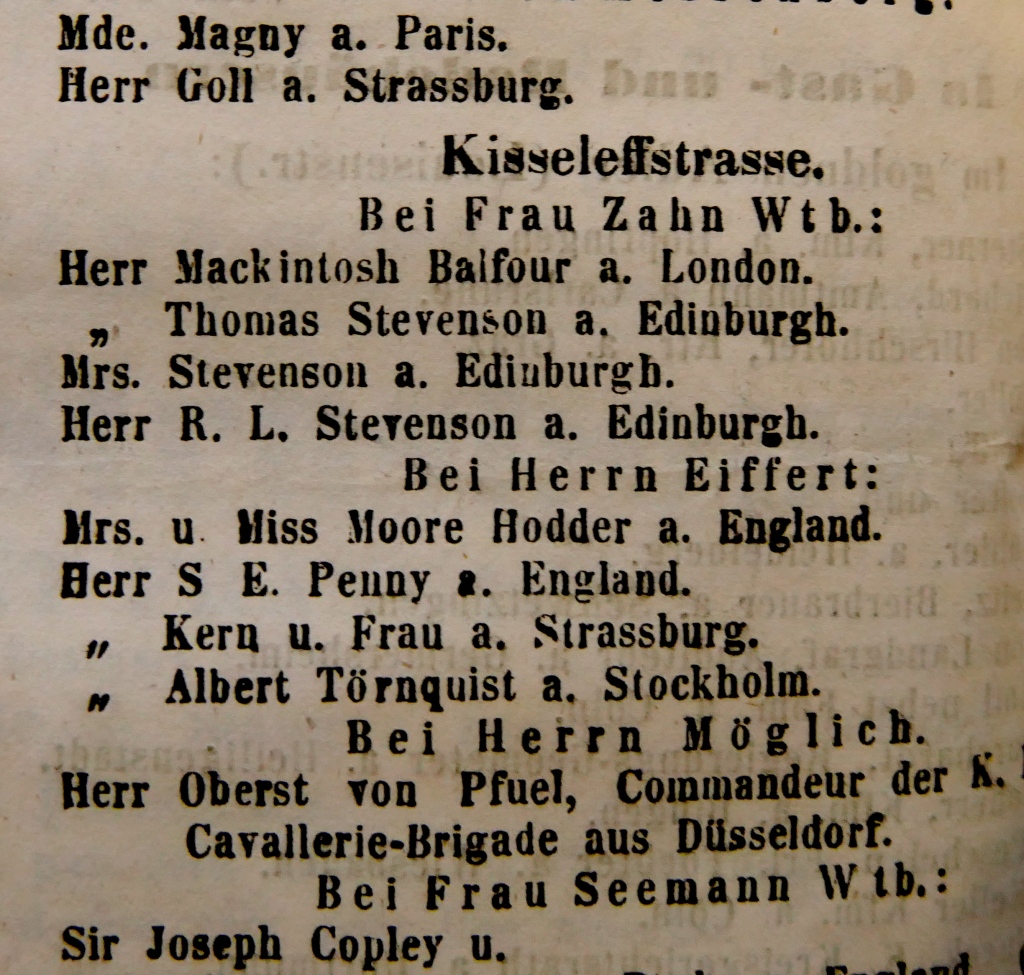

The family were among the new arrivals between 14 and 16 July announced in the Kur- und Bade-Liste dated 17 July 1862. With them was Margaret Stevenson’s brother Mackintosh Balfour, travelling to Homburg, like Thomas Stevenson, for a health cure. They all stayed at the house of the widow Zahn, No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse, a quiet street leading from the main street, Louisenstrasse, to the Park and its Casino.

Almost opposite, on the corner of Louisen- and Kisseffstrasse, was the Russischerhof, or Hotel de Russie, where the Stevenson party took their meals. The building on the corner (right) is certainly the former hotel. Stevenson later stayed in this hotel in 1875: after meeting his parents at Wiesbaden on 2 September, he travelled with them to Homburg and Mainz before leaving them to return to Paris. The Stevenson party is announced in the Homburger Fremden-Liste recording arrivals from 4 to 8 September.

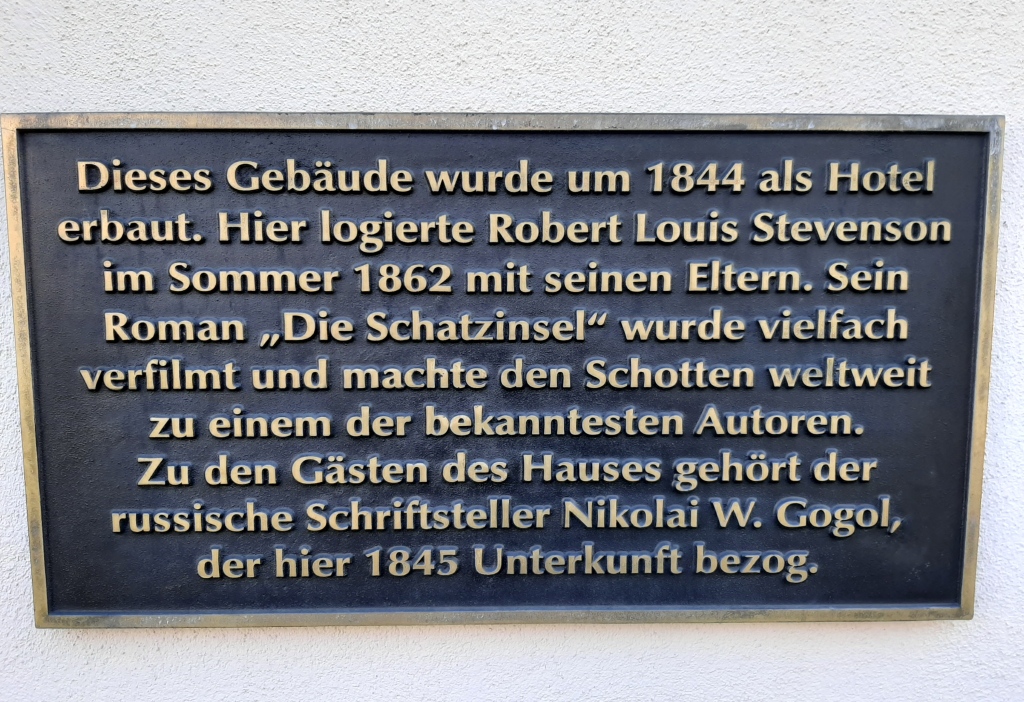

No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse (left) looks more modern. But notice a small dark rectangle on the left of the ground-floor facade. This is a plaque placed there in 2018 commemorating Stevenson’s stay (and also that of Nikolai Gogol), and the inscription starts ‘This building was built in 1844 as a hotel’, which means that the present building, at least in its basic structure and fenestration, is the one where Stevenson and his parents stayed in 1862:

The Stevenson who stayed in Homburg in 1875 was very different from the boy who stayed there in 1862: in 1875 he had graduated from University in July, had already begun publishing literary works in magazines and was in the middle of a formative experience in France living with art students. After arriving in Paris from Germany on 6 September, he proceeded to Barbizon and there met and fell in love with his future wife Fanny Osbourne.

However that early experience in Homburg remained in his memory. In late 1890, searching for subjects for a second series of Scribner’s Magazine essays he sketched out some headings for an essay on his experience of gambling establishements and then wrote a few paragraphs about Bad Homburg. Here, to end, is an extract of part of that text:

[…] I heard first in Homburg the continuous ringing of counted money on the tables of a gaming house. Sitting on the terrace, I became suddenly aware of it with a thrill of the pleasure of hearing not yet forgotten; a fine band of music played there daily, and I have forgot the music; but I think when I come to lie dying, I shall still be able to recal (as I do now) the more delicate concert from within. I thought then already, as I think still today, that there are few sounds to be compared with it in nature. It chanced I was to hear it again and yet again in the course of my vagrant life; and it is a singular thought to me now and in this far away place, that the song of the money is still going on in Europe, like the song of birds, perennial.

Homburg was then near an end; Blanc [François Blanc, director of the Homburg casino] had received a formal warning [gambling was to be outlawed in German in 1872]; he was already (as I was to see next year [1863]) timidly breaking ground elsewhere for another palace of fate [from 1860 in Monaco]; but the original establishment was still humming with gulls and ringing with their money. There were many circumstances to delight a boy abroad for the first time; the taste of mulberries; the sweet water in our house well; the English chapel opening down a long stair into an archway in the old Schloss, the pond with the carp, the vast green rambling ground of forest; the terrace before the Kursaal where the band played and the crowd of visitors walked to and fro in summer raiment […] But the centrepiece of all was that glorified garden-house that sang all day with gold and silver. The barbaric splendour of its decoration, the gold room, the patterns on the tables, the hopping of the roulette ball, the high dry voice of the croupier, the song of the money—and perhaps above all the sense that the place was a temple of wickedness, and that attraction of inverted horror which it is so easy and so dangerous to arouse in children — held me in bondage to the image of the Kursaal itself. Sometimes my father took me in, and I would wander, a twelve-year-old observer, about the crowded tables. The large liveried footmen were an awful joy to me; I had picked up that they served as spies upon the visitors; and I would place myself near one, try to follow the direction of his glances, and thrill all over with the sense of secrecy and peril. […]

Leave a comment