Archive for October 2022

RLS and French literature

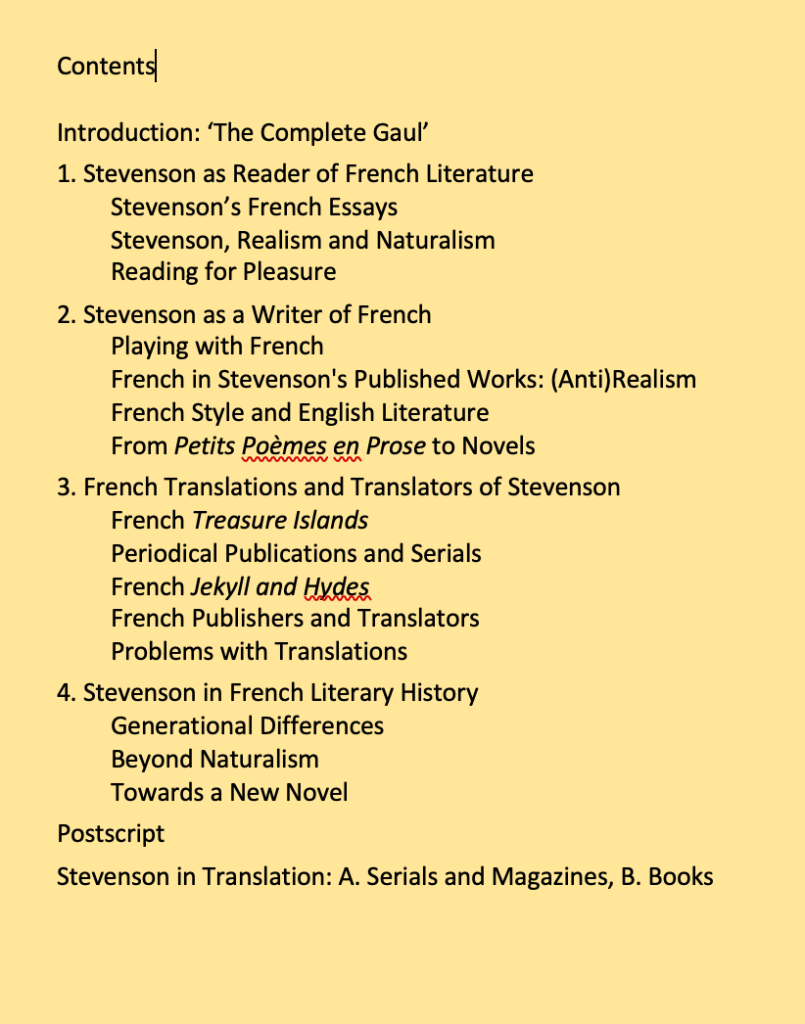

A post by Katherine Ashley: thoughts on her study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature: Literary Relations at the Fin de Siecle (EUP, 2022)

When we look at how Stevenson interpreted French literary history, how he responded to established and emerging theories of the novel in France, and how he devoured both popular and literary French novels, we can also see how all of these things informed his own writing. From the way that he argues against Naturalism in order to reassert the importance of the romance tradition, to the stylistic apprenticeship that he undertook in earnest and in jest, we see an author developing an approach to literature that went against dominant theories of the Victorian realist novel and challenged conceptions of what “the art of fiction” might entail.

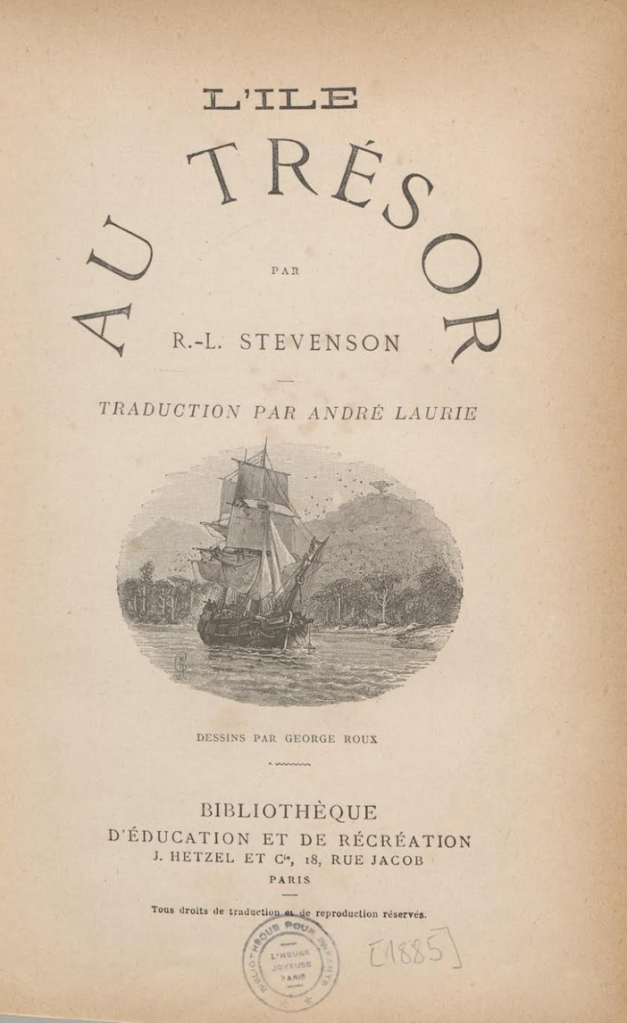

To a new generation of French writers, Stevenson became a beacon of change, presenting a pathway out of the perceived dead end that the French novel had run up against.

Naturalism, with its emphasis on scientific positivism, could only take the novel so far; Decadence, with its emphasis on aestheticism, contained the seeds of its own demise. Stevenson, translated and published in popular and highbrow venues, touted as a bestselling children’s author but also as the figurehead of a cosmopolitan revival, showed that readable page-turners could also be stylistic tours-de-force. This reminded French authors and critics that form and style could themselves be part of the intrigue and the adventure of reading and writing.

This study of reciprocal influence reveals much about the literary debates that rocked late-nineteenth-century Britain and France. To retrace the readings and the relationships – both on an individual level (Stevenson) and on a macro level (Franco-British literature) – required wading through nineteenth-century newspapers, journals, correspondence and novels. This might seem dry, but it was brought to life by the ebullient and boisterous personality at the heart of my research. Stevenson’s voice was a reminder that at the end of the day, literary history is in part the history of individuals who valued the imaginative, creative qualities of language and dedicated their lives to it. For Stevenson, being a man of letters sometimes meant “sedulously aping” literary masters, but it also involved play and fun, spontaneity and pleasure. When researching my book, it was Stevenson’s exuberant multilingual outbursts, his hilarious spoofing of contemporary writers and texts, or the silly French lessons like the one he gave to his stepson Lloyd Osbourne that brought the subject and the subject matter to life.

.

.