Archive for the ‘National Library of Scotland’ Category

Stevenson in Homburg, 1862

Stevenson visited Germany on four occasions: 1. Homburg (now Bad Homburg vor der Höhe) with his parents, July—August 1862; 2. The following year travelling home from Italy with his parents (Munich—Augsburg—Nuremberg—Frankfurt—Cologne) in May 1863; 3. Frankfurt during his first summer vacation as a student with Walter Simpson, July—August 1872; 4. And finally, for a few days, joining his parents at Wiesbaden in September 1875.

Although steeped in French culture, Stevenson was also attracted to German thought and literature.The 1872 stay in Frankfurt was to improve his German. After the death of his friend James Walter Ferrier, Stevenson remembered that Ferrier, probably in the early 1870s, ‘had [=? had made] a pretty full translation of Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters, which we read together, as well as the second part of Goethe’s Faust, […] he helping me with the German’ (Letters 4: 206). He quotes Goethe and Heine in German several times in his letters from 1872 to 1875 (Letters 1: 289, 316, 403; Letters 2: 13, 72, 81, 122) and read Heine’s love poems together with Fanny Sitwell in the summer of 1873 (Letters 2: 31).

His German experiences are reflected in ‘Will O’ the Mill’ (1878) and Prince Otto (1885) as well as an abandoned essay on Homburg, ‘An Onlooker in Hell’, for a series, planned in 1890, to be called ‘Random Memories’. This latter is now in the NLS (MS 3112, ff. 308-311) and will be published in our Essays V, presently being prepared by Lesley Graham

But to return to his first experience of Germany, not yet twelve years old, in the summer of 1862. A reader of this blog, Thomas Obst, lives a few miles from Bad Homburg and, after some local research, kindly supplies the following facts and images.

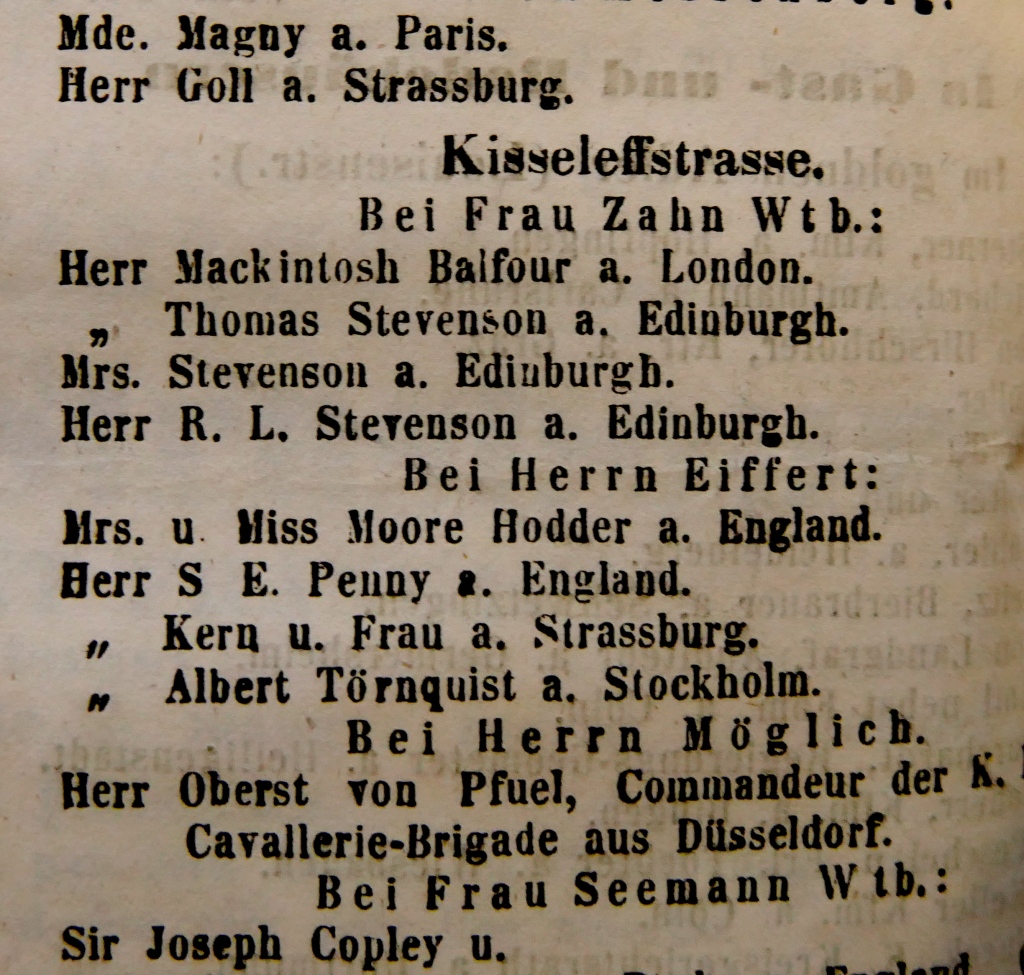

The family were among the new arrivals between 14 and 16 July announced in the Kur- und Bade-Liste dated 17 July 1862. With them was Margaret Stevenson’s brother Mackintosh Balfour, travelling to Homburg, like Thomas Stevenson, for a health cure. They all stayed at the house of the widow Zahn, No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse, a quiet street leading from the main street, Louisenstrasse, to the Park and its Casino.

Almost opposite, on the corner of Louisen- and Kisseffstrasse, was the Russischerhof, or Hotel de Russie, where the Stevenson party took their meals. The building on the corner (right) is certainly the former hotel. Stevenson later stayed in this hotel in 1875: after meeting his parents at Wiesbaden on 2 September, he travelled with them to Homburg and Mainz before leaving them to return to Paris. The Stevenson party is announced in the Homburger Fremden-Liste recording arrivals from 4 to 8 September.

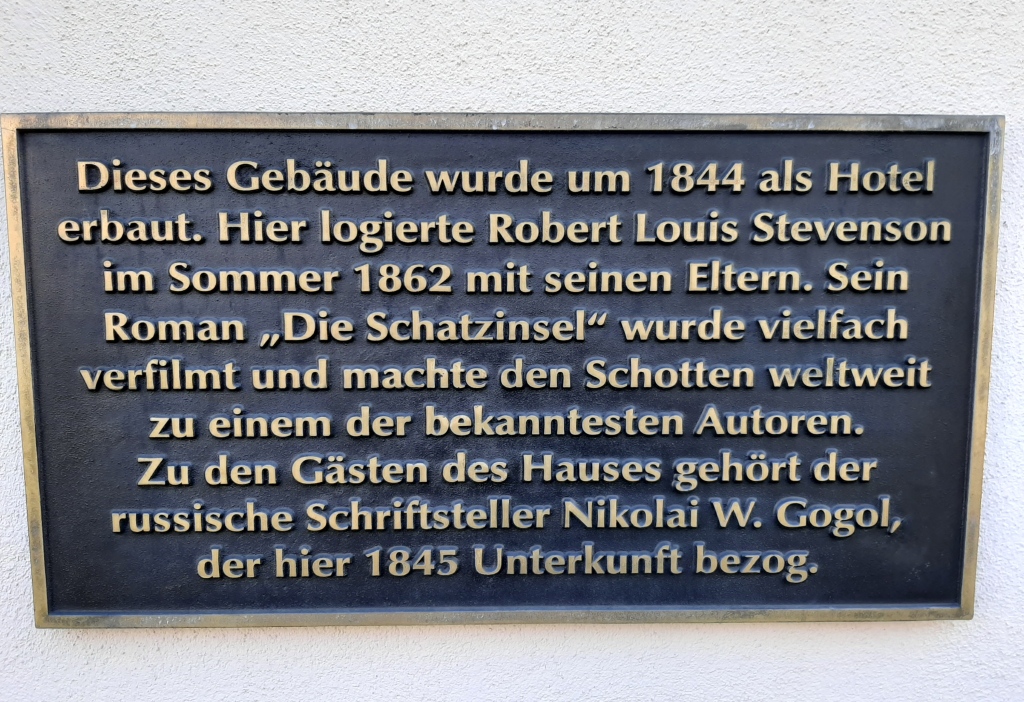

No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse (left) looks more modern. But notice a small dark rectangle on the left of the ground-floor facade. This is a plaque placed there in 2018 commemorating Stevenson’s stay (and also that of Nikolai Gogol), and the inscription starts ‘This building was built in 1844 as a hotel’, which means that the present building, at least in its basic structure and fenestration, is the one where Stevenson and his parents stayed in 1862:

The Stevenson who stayed in Homburg in 1875 was very different from the boy who stayed there in 1862: in 1875 he had graduated from University in July, had already begun publishing literary works in magazines and was in the middle of a formative experience in France living with art students. After arriving in Paris from Germany on 6 September, he proceeded to Barbizon and there met and fell in love with his future wife Fanny Osbourne.

However that early experience in Homburg remained in his memory. In late 1890, searching for subjects for a second series of Scribner’s Magazine essays he sketched out some headings for an essay on his experience of gambling establishements and then wrote a few paragraphs about Bad Homburg. Here, to end, is an extract of part of that text:

[…] I heard first in Homburg the continuous ringing of counted money on the tables of a gaming house. Sitting on the terrace, I became suddenly aware of it with a thrill of the pleasure of hearing not yet forgotten; a fine band of music played there daily, and I have forgot the music; but I think when I come to lie dying, I shall still be able to recal (as I do now) the more delicate concert from within. I thought then already, as I think still today, that there are few sounds to be compared with it in nature. It chanced I was to hear it again and yet again in the course of my vagrant life; and it is a singular thought to me now and in this far away place, that the song of the money is still going on in Europe, like the song of birds, perennial.

Homburg was then near an end; Blanc [François Blanc, director of the Homburg casino] had received a formal warning [gambling was to be outlawed in German in 1872]; he was already (as I was to see next year [1863]) timidly breaking ground elsewhere for another palace of fate [from 1860 in Monaco]; but the original establishment was still humming with gulls and ringing with their money. There were many circumstances to delight a boy abroad for the first time; the taste of mulberries; the sweet water in our house well; the English chapel opening down a long stair into an archway in the old Schloss, the pond with the carp, the vast green rambling ground of forest; the terrace before the Kursaal where the band played and the crowd of visitors walked to and fro in summer raiment […] But the centrepiece of all was that glorified garden-house that sang all day with gold and silver. The barbaric splendour of its decoration, the gold room, the patterns on the tables, the hopping of the roulette ball, the high dry voice of the croupier, the song of the money—and perhaps above all the sense that the place was a temple of wickedness, and that attraction of inverted horror which it is so easy and so dangerous to arouse in children — held me in bondage to the image of the Kursaal itself. Sometimes my father took me in, and I would wander, a twelve-year-old observer, about the crowded tables. The large liveried footmen were an awful joy to me; I had picked up that they served as spies upon the visitors; and I would place myself near one, try to follow the direction of his glances, and thrill all over with the sense of secrecy and peril. […]

Stockfish: a mystery

1. Stockfish

1. Stockfish

Stockfish is dried, unsalted cod.

2. A list of essay titles — with stockfish

Among the Graham Balfour papers in the National Library of Scotland is his transcription of Stevenson’s outline (from late 1876 or early 1877) for a book of essays to be called ‘Life at Twenty Five’. Twelve numbered chapters are followed by a shorter unnumbered list, which may be for a second part of the same volume:

At first glance, these seem to be simple pleasures that any young bohemian might enjoy. The deleted ‘Religion’ might be have been a provocative idea about which he had second thoughts, but what on earth can that ‘Stockfish’ be? It is so bizarre that I thought it could be a mistake on Balfour’s part.

3. Notes — with stockfish

Then the other day, among the material made available by the Harry Ransom Center, I saw the following at the top of a page of notes, in a rebound series of leaves from a dismembered notebook, from the same 1876-77 period:

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Manuscript Collection MS-4035, Box 1, Folder 5 (‘Notes and Fragments’), p. 1 (top of page).

Stockfish. take posterity on our backs. Act straight for | today, and remember that your theory for posterity will be | wrong. Better a straw fire of popularity than t other thing.

Stockfish again. Something tells me Balfour didn’t make a mistake.

But there was more to come. You see that pencil line at the bottom left of the image above? It goes right down to the bottom of the page (by-passing a series of quotations and translations from Montaigne) and loops around the following:

One of these vices, which have “je ne sais quoi de | genereux. || stockfish. [with uncrossed -t]

[Added 15 Nov 2015: A reader has commented that the pencil example looks like’shellfish’, but looked at carefully the vertical line following the initial-s (which I take to be an uncrossed ‘t’) is clearly followed by ‘oc’; what looks like double-l, could indeed be that but in the context it must be ‘k’, which usually looks like ‘R’ and sometimes has a more-or-less vertical second part and looks like double-l, as in the word written a few lines above this fragment:

This, believe it or not, is ‘kinds’. In the ink example, this second part of the ‘k’ has been merged with the vertical line of the ‘f’. ]

The phrase ‘je ne sais quoi de généreux’ is another quotation from Montaigne: Book II. 2 (De Yvrongnerie, / On Drunkenness), in Cotton’s translation (with a bit more context), ‘Now, among the rest, drunkenness seems to me to be a gross and brutish vice. The soul has greater part in the rest, and there are some vices that have something, if a man may so say, of generous in them; there are vices wherein there is a mixture of knowledge, diligence, valor, prudence, dexterity and address; this one is totally corporeal and earthly.’ It is a quote he remembered and reused in ‘The Character of Dogs’ (1883): ‘The canine, like the human, gentleman demands in his misdemeanours Montaigne’s “je ne sais quoi de genereux.” ’

And this too is apparently connected with stockfish.

So at the top of the page we have ethical advice that could easily go in the ‘Life at Twenty Five’ volume. The meaning is not clear, but it could be something like, ‘you should not be conditioned by the idea of posterity: take posterity with you on your back like Æneas carrying his father out of burning Troy ; it’s better to enjoy brief popularity now than to have it after your death when you can’t enjoy it at all.’ (Æneas seems a better fit than Horace’s ‘black care’ which sits behind the rider (Odes III. 1).)

And at the bottom of the page, we have some more ethical advice, here not about the choice of conduct but about judging it: some vices are low and beastly, but others have ‘generous’ aspects (perhaps involving nobility and self respect).

And both of these have something to do with stockfish…

What has ethical advice got to do with stockfish? (By the way, don’t start thinking that I’m going to find the answer to that question.) Perhaps we can get some clues from other uses of the word.

4. Stevenson and stockfish

Stevenson rarely uses the word. In ‘The Wreath of Immortelles’ (1870) he says the talk of fishmongers runs ‘usually on stock-fish and haddocks’. Fair enough. And in Weir of Hermiston (1894), the older Kirstie gives her opinion of Gib the weaver: “He’s maybe no more stockfish than his neeghbours! He rade wi’ the rest o’ them and had a good stomach to the work, by a’ that I hear!” (ch. V ‘Winter on the Moors’, 1. ‘At Hermiston’). Here, ‘stockfish’ clearly means ‘a stiff, unemotional person’ , by analogy with dried cod (and maybe Kirstie means to say ‘stockish’ and says ‘stockfish’ by applying a kind of folk etymology).

Not much help here.

5. Connotations of stockfish

Across the centuries, the metaphorical connotations of ‘stockfish’ are all negative. Falstaff uses it to berate Prince Hall :

you starveling, you eel-skin, you dried neat’s tongue, you bulls-pizzle, you stockfish (1 Henry IV II. 5. 249)

In particular it is used as noun or adjective for a stiff, unimaginative person:

the stockfish-souled reader (B. S. Naylor, Time and Truth Reconciling the Moral and Religious World to Shakespeare (London, 1854), ch. 12, 168.

a sort of stock-fish though earnest expression’ (The Examiner 557 (30 Aug 1818), 555)

mute as a stock-fish (Charles Dickens, Barnaby Rudge (1841) ch. 46)

dead as a stock-fish (George Meredith, Richard Feverel (1859) III. 5)

Faces seen in street and countryside came thronging up before him—red, stock-fish faces; hard, dull faces; prim, dry faces […] How could he know what men who had such faces thought and did?’ (John Galsworthy, The Forsyte Saga Part III. 3 ‘Irene’)

6. So, what does it mean here?

Assuming that Stevenson is using ‘stockfish’ in this tradition, we can imagine he might be adopting it for a common target of his social criticism in the 1870s: conventional, respectable, ‘stuffed shirts’, people lacking in imagination, flexibility and tolerance.

In the list apparently of essays on simple pleasures (Tobacco, Walking Tours, Wine…), ‘Stockfish’ must be an odd thought for an essay, perhaps one summarizing his thoughts on respectable society.

In the page of notes in the Harry Ransom Center, the annotation ‘stockfish’ seems to be attached to conduct contrasted with the that of respectable society. All I can suggest is that these notes made him think of negative conduct and judgments to be dealt with in the ‘Stockfish’ section or chapter.

Hmm, not very satisfying as explanations. But can anyone think of anything better?

RLS doodles map in class

Among the possible spin-offs of the Stevenson Edition is a directory of Stevenson’s notebooks with a guide to their contents. Here, for example, is a page from Notebook R (his notebooks were labelled by Graham Balfour) which is in the National Library of Scotland (MS 9904). This was used in 1867-68 for lecture notes on hydrostatics and electricity (P.G. Tait’s natural philosophy course); on p. 44, there is a list of 11 plays, beginning ‘Edmund Fuller Tragedy in five acts’; p. 40 ff. contains a draft of Act II, sc. iii of one of these (‘The Brothers’, a comedy about ‘a discovered will’); and on p. 17, there is doodled map of an island with a bay and small island within it and a long promontory that has an interesting family resemblance with the map drawn in 1881 for Treasure Island

Among the possible spin-offs of the Stevenson Edition is a directory of Stevenson’s notebooks with a guide to their contents. Here, for example, is a page from Notebook R (his notebooks were labelled by Graham Balfour) which is in the National Library of Scotland (MS 9904). This was used in 1867-68 for lecture notes on hydrostatics and electricity (P.G. Tait’s natural philosophy course); on p. 44, there is a list of 11 plays, beginning ‘Edmund Fuller Tragedy in five acts’; p. 40 ff. contains a draft of Act II, sc. iii of one of these (‘The Brothers’, a comedy about ‘a discovered will’); and on p. 17, there is doodled map of an island with a bay and small island within it and a long promontory that has an interesting family resemblance with the map drawn in 1881 for Treasure Island

.