Archive for the ‘New publication’ Category

Stevenson in Homburg, 1862

Stevenson visited Germany on four occasions: 1. Homburg (now Bad Homburg vor der Höhe) with his parents, July—August 1862; 2. The following year travelling home from Italy with his parents (Munich—Augsburg—Nuremberg—Frankfurt—Cologne) in May 1863; 3. Frankfurt during his first summer vacation as a student with Walter Simpson, July—August 1872; 4. And finally, for a few days, joining his parents at Wiesbaden in September 1875.

Although steeped in French culture, Stevenson was also attracted to German thought and literature.The 1872 stay in Frankfurt was to improve his German. After the death of his friend James Walter Ferrier, Stevenson remembered that Ferrier, probably in the early 1870s, ‘had [=? had made] a pretty full translation of Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters, which we read together, as well as the second part of Goethe’s Faust, […] he helping me with the German’ (Letters 4: 206). He quotes Goethe and Heine in German several times in his letters from 1872 to 1875 (Letters 1: 289, 316, 403; Letters 2: 13, 72, 81, 122) and read Heine’s love poems together with Fanny Sitwell in the summer of 1873 (Letters 2: 31).

His German experiences are reflected in ‘Will O’ the Mill’ (1878) and Prince Otto (1885) as well as an abandoned essay on Homburg, ‘An Onlooker in Hell’, for a series, planned in 1890, to be called ‘Random Memories’. This latter is now in the NLS (MS 3112, ff. 308-311) and will be published in our Essays V, presently being prepared by Lesley Graham

But to return to his first experience of Germany, not yet twelve years old, in the summer of 1862. A reader of this blog, Thomas Obst, lives a few miles from Bad Homburg and, after some local research, kindly supplies the following facts and images.

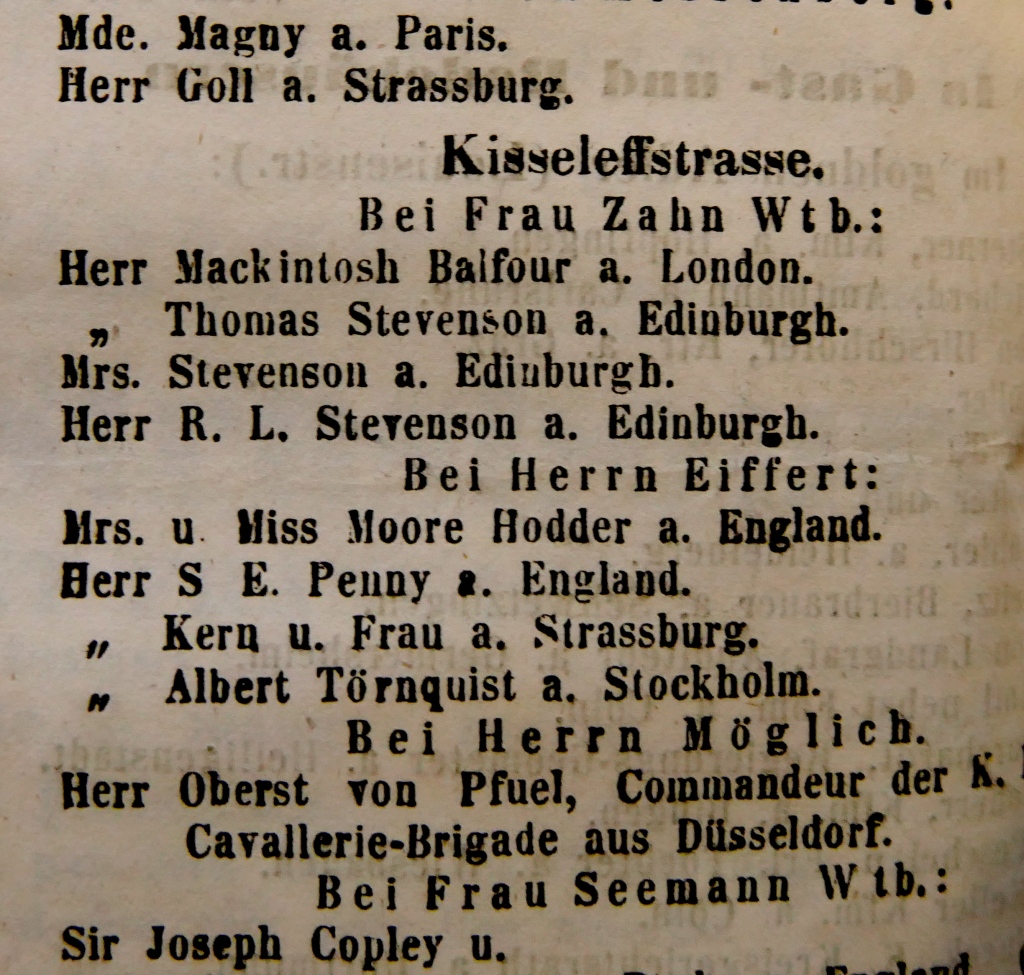

The family were among the new arrivals between 14 and 16 July announced in the Kur- und Bade-Liste dated 17 July 1862. With them was Margaret Stevenson’s brother Mackintosh Balfour, travelling to Homburg, like Thomas Stevenson, for a health cure. They all stayed at the house of the widow Zahn, No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse, a quiet street leading from the main street, Louisenstrasse, to the Park and its Casino.

Almost opposite, on the corner of Louisen- and Kisseffstrasse, was the Russischerhof, or Hotel de Russie, where the Stevenson party took their meals. The building on the corner (right) is certainly the former hotel. Stevenson later stayed in this hotel in 1875: after meeting his parents at Wiesbaden on 2 September, he travelled with them to Homburg and Mainz before leaving them to return to Paris. The Stevenson party is announced in the Homburger Fremden-Liste recording arrivals from 4 to 8 September.

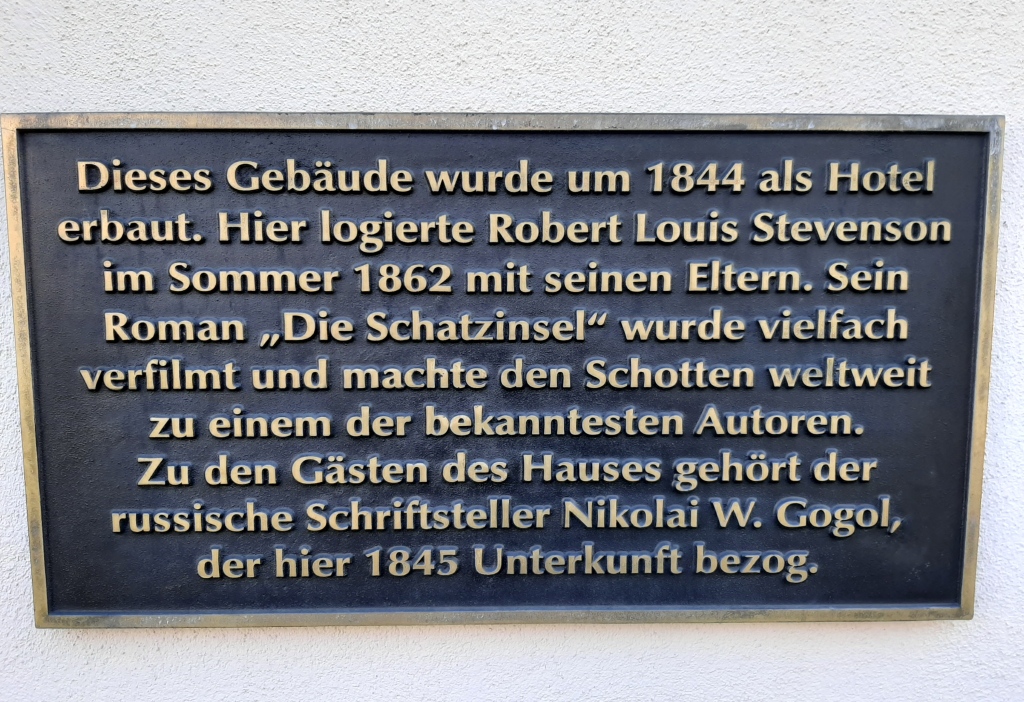

No. 3 Kisseleffstrasse (left) looks more modern. But notice a small dark rectangle on the left of the ground-floor facade. This is a plaque placed there in 2018 commemorating Stevenson’s stay (and also that of Nikolai Gogol), and the inscription starts ‘This building was built in 1844 as a hotel’, which means that the present building, at least in its basic structure and fenestration, is the one where Stevenson and his parents stayed in 1862:

The Stevenson who stayed in Homburg in 1875 was very different from the boy who stayed there in 1862: in 1875 he had graduated from University in July, had already begun publishing literary works in magazines and was in the middle of a formative experience in France living with art students. After arriving in Paris from Germany on 6 September, he proceeded to Barbizon and there met and fell in love with his future wife Fanny Osbourne.

However that early experience in Homburg remained in his memory. In late 1890, searching for subjects for a second series of Scribner’s Magazine essays he sketched out some headings for an essay on his experience of gambling establishements and then wrote a few paragraphs about Bad Homburg. Here, to end, is an extract of part of that text:

[…] I heard first in Homburg the continuous ringing of counted money on the tables of a gaming house. Sitting on the terrace, I became suddenly aware of it with a thrill of the pleasure of hearing not yet forgotten; a fine band of music played there daily, and I have forgot the music; but I think when I come to lie dying, I shall still be able to recal (as I do now) the more delicate concert from within. I thought then already, as I think still today, that there are few sounds to be compared with it in nature. It chanced I was to hear it again and yet again in the course of my vagrant life; and it is a singular thought to me now and in this far away place, that the song of the money is still going on in Europe, like the song of birds, perennial.

Homburg was then near an end; Blanc [François Blanc, director of the Homburg casino] had received a formal warning [gambling was to be outlawed in German in 1872]; he was already (as I was to see next year [1863]) timidly breaking ground elsewhere for another palace of fate [from 1860 in Monaco]; but the original establishment was still humming with gulls and ringing with their money. There were many circumstances to delight a boy abroad for the first time; the taste of mulberries; the sweet water in our house well; the English chapel opening down a long stair into an archway in the old Schloss, the pond with the carp, the vast green rambling ground of forest; the terrace before the Kursaal where the band played and the crowd of visitors walked to and fro in summer raiment […] But the centrepiece of all was that glorified garden-house that sang all day with gold and silver. The barbaric splendour of its decoration, the gold room, the patterns on the tables, the hopping of the roulette ball, the high dry voice of the croupier, the song of the money—and perhaps above all the sense that the place was a temple of wickedness, and that attraction of inverted horror which it is so easy and so dangerous to arouse in children — held me in bondage to the image of the Kursaal itself. Sometimes my father took me in, and I would wander, a twelve-year-old observer, about the crowded tables. The large liveried footmen were an awful joy to me; I had picked up that they served as spies upon the visitors; and I would place myself near one, try to follow the direction of his glances, and thrill all over with the sense of secrecy and peril. […]

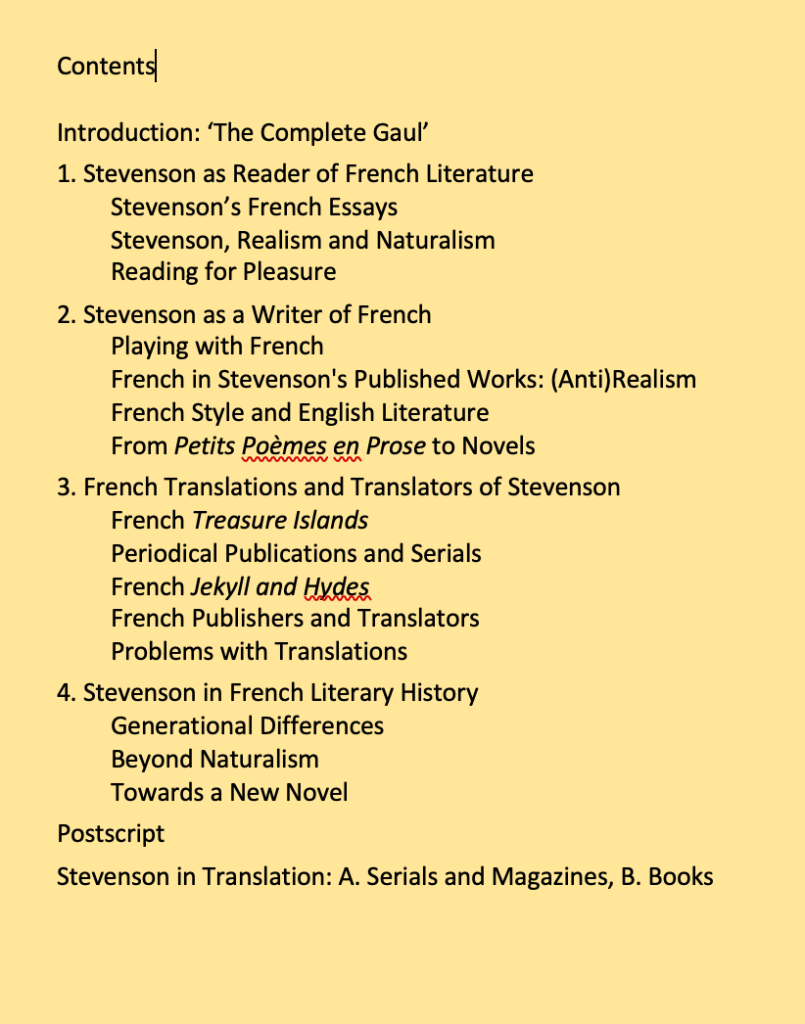

RLS and French literature

A post by Katherine Ashley: thoughts on her study Robert Louis Stevenson and Nineteenth-Century French Literature: Literary Relations at the Fin de Siecle (EUP, 2022)

When we look at how Stevenson interpreted French literary history, how he responded to established and emerging theories of the novel in France, and how he devoured both popular and literary French novels, we can also see how all of these things informed his own writing. From the way that he argues against Naturalism in order to reassert the importance of the romance tradition, to the stylistic apprenticeship that he undertook in earnest and in jest, we see an author developing an approach to literature that went against dominant theories of the Victorian realist novel and challenged conceptions of what “the art of fiction” might entail.

To a new generation of French writers, Stevenson became a beacon of change, presenting a pathway out of the perceived dead end that the French novel had run up against.

Naturalism, with its emphasis on scientific positivism, could only take the novel so far; Decadence, with its emphasis on aestheticism, contained the seeds of its own demise. Stevenson, translated and published in popular and highbrow venues, touted as a bestselling children’s author but also as the figurehead of a cosmopolitan revival, showed that readable page-turners could also be stylistic tours-de-force. This reminded French authors and critics that form and style could themselves be part of the intrigue and the adventure of reading and writing.

This study of reciprocal influence reveals much about the literary debates that rocked late-nineteenth-century Britain and France. To retrace the readings and the relationships – both on an individual level (Stevenson) and on a macro level (Franco-British literature) – required wading through nineteenth-century newspapers, journals, correspondence and novels. This might seem dry, but it was brought to life by the ebullient and boisterous personality at the heart of my research. Stevenson’s voice was a reminder that at the end of the day, literary history is in part the history of individuals who valued the imaginative, creative qualities of language and dedicated their lives to it. For Stevenson, being a man of letters sometimes meant “sedulously aping” literary masters, but it also involved play and fun, spontaneity and pleasure. When researching my book, it was Stevenson’s exuberant multilingual outbursts, his hilarious spoofing of contemporary writers and texts, or the silly French lessons like the one he gave to his stepson Lloyd Osbourne that brought the subject and the subject matter to life.

.

.

Stevenson and Pacific Christianity

A post contributed by L. M. Ratnapalan

author of Robert Louis Stevenson and the Pacific: The Transformation of Global Christianity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, March 2023)

Studying Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pacific writings and their contribution to anthropology, I was struck by their many references to religion: local beliefs and practices, churches, nuns, pastors, and converts. The published studies of Stevenson that I read focussed almost entirely on his view of Western missionaries. The consensus was: he was a critical friend of missionaries considering them to be ‘by far the best and the most useful whites in the Pacific’, but that he found their attempts to change Polynesian habits led to consequences that were ‘bloodier than a bombardment’.(1) These studies, however, typically paid little attention to the wider world of Pacific Christianity. Above all, the indigenous Christians Stevenson wrote so much about were hardly discussed at all.

I believe that the reasons for this are at least partly cultural. Growing up in Britain, I had come to think of Christianity as a personal belief, held by a diminishing number of people, who mainly practiced it in private. But when I moved to South Korea in 2012 I was struck by the centrality of Christianity, its practices and discourses, even in a modern city like Seoul: bright crosses light up the night sky; people pray with a rosary in the park; Church attendance is important; and the most popular evening talk show featured a famous pastor as a weekly contributor.

While living in Britain, I had gained the impression that organized religion was everywhere in decline and that secularization was the dominant force; now I could see that the bigger story was not the shrinking of religious affiliation but rather the explosive growth of Christianity (and Islam). The religious picture of the world was undergoing transformation and the key agents were indigenous Christians from Africa, Asia, South America, and the Island Pacific.(2) The vast majority of the world’s Christians now live outside Europe.(3)

In most Pacific Islands comfortably 95 per cent of the population describe themselves as Christian.(3) With this understanding, I felt that I was in a better position to analyze Stevenson’s South Seas writing. A well-known image of the author and his family in Samoa will help to explain what I mean.

Seated and standing around the Stevensons, Osbournes, and their maid are Pacific Islanders, but who were they? The household retinue was composed not only of Samoans but also of Islanders from many other parts of the Pacific. For example, while the cook Talolo (seated directly in front of RLS) was Samoan, Savea (seated far left), who worked on the plantation, was probably a Wallis Islander, and Arrick (seated in front of Talolo) was from the New Hebrides. Yet though they originated from widely separated communities, they were united in a common Christian culture. The workers on the Stevenson estate reflected a mobile Pacific world in which Christianity was common currency, a situation also reflected in Stevenson’s writings, featuring the Pacific-wide movement of Islanders and religious talk.

My project developed to become a study of the impact of Pacific Islands Christianity on Robert Louis Stevenson. I argue that ‘the Beach of Falesá’ could be seen as a meditation on the social effects of missionaries in the Islands.(5) His Pacific fiction deserves reassessment, I thought, in the light of his fascination with the difference between Islanders’ adoption of Christianity as an outward façade (‘indigenization’) and a deeper cultural and spiritual engagement with it (‘inculturation’).(6) The quickness with which he was able to absorb what he experienced was remarkable. During the period 1888–94, as he moved from Pacific traveller to Samoan resident, he progressed from a somewhat sceptical assessment of the efficacy of local religious conversions to a view that mixed the personal with the political. (7) In a forthcoming book, I explore how his Scottish Presbyterian upbringing guided Stevenson’s understanding of Pacific culture, and how Pacific Islanders in turn helped to change the way that he thought about Christianity.(8)

A personal shift of viewpoint has produced these conclusions. Stevenson once wrote that ‘There is no foreign land; it is the traveller only that is foreign’.(9) In the Pacific, he found that ideas such as Christianity could also cover great distances to become foreign to the traveller, and so light up ‘the contrasts of the earth’.

L. M. Ratnapalan, Yonsei University

(1) Robert Louis Stevenson, In the South Seas (London: Penguin, 1998), 64, 34.

(2) Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith

(New York: Orbis, 1996); Jehu J. Hanciles, Migration and the Making of Global Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2021).

(3) Pew Research Center, ‘Global Christianity – A Report on the size and distribution of the World’s Christian population’ (2011): https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2011/12/19/global-christianity-exec/

(4) Kenneth R. Ross, Katalina Tahaafe-Williams, and Todd M. Johnson, eds. Christianity in Oceania

(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021).

(5) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘Missionary Christianity and Culture in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Beach of Falesá”’, Religion and Literature, 53.3 (2021).

(6) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘Half Christian: Indigenization and Inculturation in Stevenson’s Pacific Fiction’, Scottish Literary Review 12, 1 (2020).

(7) L. M. Ratnapalan, ‘“Our Father’s Footprints”: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Anthropology of Conversion, 1888-1894’, Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, 11.1 (forthcoming).

(8) L. M. Ratnapalan, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Pacific: The Transformation of Global Christianity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, scheduled March 2023).

(9) Robert Louis Stevenson, The Silverado Squatters (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1884), 113-4.

Images

Vailima family: https://www.thenational.scot/news/17887450.story-samoas-love-robert-louis-stevenson/

Upcoming volume: https://edinburghuniversitypress.com/book-robert-louis-stevenson-and-the-pacific.html