Archive for October 2013

Scribner’s and Weir: a premature ‘puff’

This post is contributed by Glenda Norquay, presently working an edition of St. Ives for the Edition.

.

In my last few days at Princeton I found an interesting little twist to the tangled narrative of Stone & Kimball and Scribner’s and the competition for his late fiction.

So sure were Scribner’s that they were going to get the publication rights of Weir of Hermiston in the United States that their editor, E.L. Burlingame wrote to Sidney Colvin on the 5 September 1895:

There is one other great kindness that you could do us in this matter and that I think would be a great factor in the success of the publication. You have mentioned in your letters that both you and Henry James who had read “Weir of Hermiston” thought it beyond comparison the finest thing that Stevenson had done. If you were willing to let us quote you both as holding this opinion, and if you care to express it in words which imply a comparison, to let us quote you as saying that it reaches at least his highest level – I can think of nothing that would so quickly lead to the favorable recognition of our announcement of it. “The Fables”, the paper of extracts from the “Vailima Letters”, and perhaps the beginning of “St Ives” all preceding it, and two of them being comparatively minor things (of course I do not speak of the “Vailima” book) it is most important for us to prevent in the public mind the idea that this is a small matter, and to make known the truth that it is really the one upon which his ambition was specially centred during his last two or three years.

(1894 November 15 – 1895 September 13; 1894 November 15 – 1895 September 13; Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, Box 901; Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.)

While the evaluation of the other works as ‘small’ may be questioned (especially by the editor of one of them), the publishers were clearly aiming to make as much of Weir as they possibly could. Yet by the end of the year (9 December) Charles Scribner has this to communicate to Lemuel Bangs, their London representative:

There is nothing further to record about Stevenson’s story; it has been sold to the Cosmopolis and Stone & Kimball will publish it in this country. Baxter’s contract with Stone & Kimball knocked us out … but it was a high price to pay for an incomplete story and all things considered perhaps we are well off without it.

(L. W. Bangs; 1893 February-1900 January; Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, Box 972; Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.)

As my earlier blog noted, however, this did not diminish Scribner’s eventual pleasure in gaining control of all Stevenson’s work in the U.S..

Beinecke Library to close for a year

The Beinecke Library (which easily has the most extensive collection of Stevenson books and manuscripts in the world) has been holding celebrations for its 50th anniversary, ending with a lecture by Umberto Eco on “the library” (which he began by saying that the labyrinthine stacks of Yale’s Sterling Library had inspired the Library in The Name of the Rose. Anyone who has been there can understand this).

However, fifty years (alas!) is a long time and the Library will be closing for a whole year for extensive renovations (indicated as the academic year 2015–16, though exact dates have not yet been released).

The Library service will continue, probably based in the Sterling Library reading room, but as materials will be stored off site, deliveries and perhaps services like photoreproduction will be less rapid than their present excellent standards.

Another result is that the fellowship program will be suspended for a year: applications by this December will be for residence and study from September to December 2014 only; then after skipping a year, the next applications (December 2015) will be for residence and study in the academic year 2016-17.

Elusive London

Missing book

Have you ever had that experience of approaching open-stack shelving, and seeing a gap at about the point where the book you want should be, and—first fearing, then hoping against hope, then knowing—as you reach the spot and trace your finger right and left along the call-numbers on the spines that, yes: the gap corresponds to that very book?

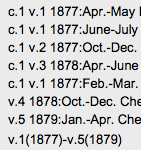

I had a similar experience the other day in the Beinecke Library with Robert-Louis Abrahamson, when we called up their copy of London (remember: the only copy outside the British Library and that one now “in quarantine”). The months from July to September, we had discovered, possibly contained four ‘articles’ by RLS. H ere are the holdings—a full set, you might think, covering 1877-79. But when the ponderous volumes arrived and I asked for the one covering July to September 1878, I discovered that there is a curious gap in the series: that very period.

ere are the holdings—a full set, you might think, covering 1877-79. But when the ponderous volumes arrived and I asked for the one covering July to September 1878, I discovered that there is a curious gap in the series: that very period.

(By the way, if the image comes out ‘squashed’, just click on it and then use the back button: this works for me.)

Presumably Edwin Beinecke had these copies made (they are negative photographic prints but perfectly legible) and would have had the whole series. Has one been lost? But how does you lose such a bulky and weighty item?

After this, I sent an email to the British Library Newspaper Division, on the off-chance—but they replied saying there’s no chance of having a look at London before March 2014.

Slight compensation

RLA and myself are working in the Beinecke on adjacent tables and the day after this disappointment he handed me this letter from Bob to Henley of December 1878:

Much obliged for London and Article on the Pictures by you of course. There was one on evidence in Court which I concluded Louis to have written or suggested for many reasons.

So here we have something to look at in one of the volumes at Yale—not seriously expecting anything but curious to see why (apart form the subject-matter) Bob might have thought it was by RLS. …Except that I had already checked in the volumes, and the full catalogue entry now reads:

“v. 4 1878: Oct.-Dec. Checked Out – Due on 04-16-2014”! No, I don’t believe it: already checked out again and due back on 16 April? No, that must refer to the period we were given to consult the volumes, with the record not yet updated. Mustn’t it?

“v. 4 1878: Oct.-Dec. Checked Out – Due on 04-16-2014”! No, I don’t believe it: already checked out again and due back on 16 April? No, that must refer to the period we were given to consult the volumes, with the record not yet updated. Mustn’t it?

Weir of Hermiston MS in Philadelphia

This post is contributed by Glenda Norquay, presently working an edition of St. Ives for the Edition.

.

Free Library of Philadelphia

image: Quondam – a virtual museum of architecture

.

While in Princeton I took a day’s excursion to The Free Library in Philadelphia to look at the manuscript fragment from Weir of Hermiston that I had uncovered through scrolling through their rather labyrinthine finding aid. The Rare Books collection holds a surprising amount of RLS, as Richard noted in his previous post (Stevenson MSS in Philadelphia). I could, however, only secure a two and a half hour slot in their tiny (two desk) reading room. The Free Library building on Vine Street is wonderful: enormously grand and imposing both outside and within, but also clearly a very well-used building, with a range of public reading rooms and plenty of people using them.

The Rare Books collection is housed on the third floor, accessed only by lift, and I had to wait some time (standing under the scrutiny of a video camera) before someone came to answer my call on the bell. The reading room is, as they said, a city block’s walk away from the entrance. The staff however could not have been more welcoming or helpful.

‘Weir’ fragment

I was given space, time, and a magnifying glass with which to study the single sheet fragment, folded into four pages. The pages are stained and creased, once folded into a pocket-sized package. The content is draft of a key episode in the novel : the ending of the chapter entitled ‘A Leaf from Christina’s Psalm-Book’, and details Kirstie’s return from meeting Archie and her mixed feelings of guilt, pleasure – and anxiety when Dand notices her pink stocking. I will leave it to Weir’s editor, Gill Hughes, to report on the significance of the pages but it is clearly a useful addition to our understanding of the novel’s composition.

FLP Rare Books Department

Time, of course, flew past in the reading room but just before the Rare Books Department was closed for the day Reference Librarian Joseph Shemtov very kindly took me for a tour of their magnificent William Elkins room. As their website notes:

The bequest of William McIntire Elkins, who died in 1947, brought his entire library, containing major collections of Oliver Goldsmith, Charles Dickens and Americana, as well as miscellaneous literary treasures. With the Elkins bequest came the gift of the room itself with its furnishings, through the generosity of his heirs. The installation of the 62-foot-long paneled Georgian room in the third floor of the Central Library at Logan Square took place over the next two years, and the Rare Book Department opened in 1949.

I was able to see Charles Dickens’ desk, the wonderful collection of books, and even the stuffed raven owned by Dickens that had inspired Edgar Allen Poe. The Library runs a tour of the room once a day.

Although it can be a challenge to navigate their website, the Free Library is well worth a visit. I was even able to purchase an Edgar Allan Poe finger-puppet with which to converse in those evenings after the Princeton Reading Room closes. Have I been here too long…?

Scribner’s and Stevenson’s posthumous works

This post is contributed by Glenda Norquay, presently working an edition of St. Ives for the Edition.

.

With the kind support of a Friends of the Princeton Library grant, I have been working in the Rare Books Room, Firestone Library, on a larger project that has emerged out of the editing of St Ives. Although my focus is on a network of transatlantic conversations between writers and publishers, Stevenson is of course a key figure.

♦

Baxter takes Stevenson business away from Scribner’s

One of the most difficult exchanges in publishing negotiations around St Ives relates to Charles Baxter’s selling the rights to Stone & Kimball rather than Stevenson’s established publishing house in the States, Charles Scribner’s Sons (see my previous post ‘Baxter takes on American publishers and gives it to them straight’). Yesterday I found a typed letter from Frank Doubleday, Scribner’s Business Manager, dated 7 December 1895, describing an encounter with Kimball:

I have just been in Stone Kimball’s offices and Kimball tells me he has signed the contract for “St Ives” and “The Weir of Hermiston”. I asked him if he paid so much for it that he will have trouble getting his money back. He replied that I need not bother about that and that he got them at a very reasonable price. He also stated that the Vailima letters sold so well that he cannot print them rapidly enough, to all of which I listened to with attention. The serial rights of “Hermiston” he has sold to Fisher Unwin and the novel is to appear in English, French and German in his magazine Cosmopolis which I suppose you know.

[Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, C0101 Box 160, F. 11]

Although aware of the tensions around this particular deal, I enjoyed what appears to be a restrained bitterness in Doubleday’s account of a particularly galling situation for them.

♦

Stone & Kimball go bankrupt

In the end of course Stone & Kimball suffered such significant financial losses, partly because of their Stevenson dealings, that their business collapsed. Scribner’s then had the satisfaction of publishing St Ives in its American book form.

A letter from Arthur Scribner , 24 March 1896, suggests some enjoyment of the situation:

From several sources we learned that Stone & Kimball were hard up, the elder Mr Stone is tired putting up the money, perhaps is a little short himself, and have more inclination that they might be willing to part with Mr Stevenson’s rights.

[Arthur Scribner sets out the terms of a possible deal, commenting:]

‘The price for The Weir & St Ives seems very high at this time now that the Stevenson’s boom has a little subsided, but it does seem to me that the whole amount secured by us would be most valuable in the end.

[Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, C0101 Box 160 F.16].

.♦

An old friend at Scribner’s, Edward L. Burlinghame

As the Scribner’s editor who worked most closely with Stevenson, Edward L. Burlingame had also been deeply disappointed, on a personal as well as business level, with the apparent snubbing of Scribner’s. He remained, however, a staunch enthusiast for R.L.S. as a late letter (9 July 1914 ), reflecting on the dangers of a writing having too ‘English’ a frame of reference indicates: Galsworthy’s work, he thought:

seemed to me to have considerable difficulties, not only in his rather pronounced English environment and association rather than his point of view (you see what I mean by the distinction), but because he doesn’t have quite the appeal to the human being as distinguished from the literary reader which seems so essential to the full success of end–papers and similar month-to-month essays. Stevenson of course even in his most ‘literary’ moments had this in the highest degree.

[Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, C0101 Box 160 F.10]

More on Stevenson’s music

The Inland Voyage Notebook

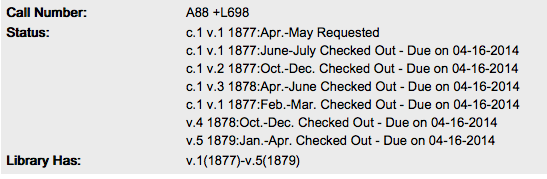

Yale, GM 664 box 3 folder 851, Inland Voyage Notebook (Notebook 27/A), opp. numb. p. 27; part of ‘The Guager’s Flute’

The ‘Inland Voyage’ Notebook gives an idea of an amazing period of literary activity and inventiveness for RLS: not only does it contain the complete first draft of An Inland Voyage, something new in travel writing, but also notes for what became The New Arabian Nights, stories that appeared immediately as startlingly modern and irreverent, and for Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, another original work with a a distinctive, idiosyncratic voice.

On the last page of the Notebook, among the notes for Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes is the single word ‘Guager’ [sic] as a reminder of the story about the excise officer (gauger) who played ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’ on his flute as a warning as he approached his friend’s distillery. This must have stimulated RLS to compose (or recover and rewrite) ‘The Gauger’s Flute’ on another page, which then becomes ‘A Song of the Road’ in Underwoods. In the published version, the place of composition is added at the bottom ‘Forest of Montargis, 1878’, a place near Fontainebleau where RLS stayed in August 1878 before leaving for a journey associated with another outstanding work, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes.

Lewis (Collected Poems, 397-99) gives information about the four manuscripts and an idea about history of composition, but as for the quotation ‘Over the hills and far away’, the only information he supplies is that it is ‘the refrain of a popular song’.

The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson

Now anyone wanting to find out more about the song and its relation to Stevenson’s poem can consult John Russell’s site The Music of Robert Louis Stevenson (aptly abbreviated as MORLS). Here, he deftly establishes the exact version that RLS would have been mentally referring to as he wrote. In fact, the poem not only quotes the song but is ‘in lockstep’ syllable-by-syllable with the Jacobite version published in James Hogg’s Jacobite Relics of Scotland.

Stevenson MSS in Philadelphia

A few days ago, Glenda Norquay, researching in Princeton for her edition of St. Ives, came across the Literary MSS finding aid of the Free Library of Philadelphia, and saw that it contains, unexpectedly, sixteen RLS manuscripts. A few of these were catalogued by the Library when Roger Swearingen’s compiled his Prose Works of Robert Louis Stevenson and are found there (the Earraid sketchbook, the fragment of Sophia Scarlet), but this new finding aid (published 2012) reveals a number of items (subsequently acquired or catalogued) that came as a complete surprise:

Autograph manuscript signed (fragment) of Weir of Hermiston. 4 pages

Two copies of Deacon Brodie with corrections in Stevenson’s hand

Corrected proof sheets of Memories and Portraits (‘1 volume’—no information on the number of pages; could this be proofs for the whole volume?)

South Seas material, from “Part V. The Gilberts. XLVIII. Butaritari”, 2 pp.

MS of part of ch XIX of The Wrecker (probably precede the 5 leaves at Princeton), 19 leaves, making this the most important fragment of MS material of this work

Corrected copy of Father Damien

Fragment of Weir of Hermiston, 4 pp.

Autograph manuscript signed (draft) of several verses and revisions, with a sketch, 1 page (“Previously identified as intended for A Child’s Garden of Verses, but unpublished there.”)

A finding aid to finding the finding aid

Archive material may be fully available and exhaustively catalogued, but sometimes the catalogue (or the MS finding aid) is very difficult to find. When Gill Hughes told me about Glenda’s discovery, I went to the home page of the FLP and searched for ‘special collections’, ‘rare books’ and manuscripts’—no joy. Then I tried the green side-tab ‘Explore’, and then the top-tab ‘Find a location’—but for all my exploration, never a thing did I find. So I tried ‘Programs and Services’ (could that cover library departments?) and finally found ‘Rare Books Department’. Hooray! So I clicked on that, clicked on ‘Collections’ and then on ‘Literature – Learn more’ which contained links to… only two finding aids: Dickens and Poe. No mention of Stevenson. I’d reached a dead-end.

Research in these labyrinths his slaves detains…

In the meantime a kind friend sent me the pdf, but I was determined to find the dang thing myself. This is how I did it: I clicked on Ask, made a desultory stab at Browse or Search FLP Knowledge Base (who knows?), browsed, searched, then found and clicked ‘Rare Books’ (I’d been given a help: Gill had told me the department was called by that name); this took me to Rare Books FAQ, where FAQ-18 is ‘Does the Rare Book Department have any finding aids?’ The brief answer to this has a clickable link which—unlike that decoy Rare Books page with only two finding aids—had the whole list. I’d finally reached the centre of the maze with the champaign luncheon! And there it was: Literary Manuscripts Collection, readable online or downloadable as pdf.

Stevenson and London magazine

RLA, me and Colindale

Last January two Essays Editors, RLA and myself, set off from Linton near Cambridge, to drive down to the Colindale Newspaper Library in North London. Our aims: to read through Young Folks (to see if the two MS papers for juvenile readers on Writing and Reading had by chance been published there—they hadn’t), and to try to identify possible articles by Stevenson in London: the conservative weekly journal of politics, finance, society and the arts.

Last January two Essays Editors, RLA and myself, set off from Linton near Cambridge, to drive down to the Colindale Newspaper Library in North London. Our aims: to read through Young Folks (to see if the two MS papers for juvenile readers on Writing and Reading had by chance been published there—they hadn’t), and to try to identify possible articles by Stevenson in London: the conservative weekly journal of politics, finance, society and the arts.

Time passed quickly on the journey as we discussed a draft of the Edition’s General Introduction; we then successfully identified just the right place to turn for the Library, and (still feeling good about that) quickly found a parking place. The suburb and the Library building are from the 1930s and the Library had a certain old-fashioned charm: we registered at a ground-floor cloakroom window, then went up to a first-floor reading-room that reminded me of a 1950s town library in its slight workaday disorder.

Day in the Library

The opening hours not being generous (10 am to 5 pm), we got down to work as soon as the sturdily-bound volumes arrived. I was surprised to see the London was actually in broadsheet newspaper format, and was impressed by the accurate printing on thick white paper. Each printed letter pressed, slightly but sharply, into the paper. Running your fingers over the surface, you could feel the indented shapes on your finger-tips.

The opening hours not being generous (10 am to 5 pm), we got down to work as soon as the sturdily-bound volumes arrived. I was surprised to see the London was actually in broadsheet newspaper format, and was impressed by the accurate printing on thick white paper. Each printed letter pressed, slightly but sharply, into the paper. Running your fingers over the surface, you could feel the indented shapes on your finger-tips.

All this I was unconsciously taking in as I started to rapidly leaf through the pages. I saw that the typical contents included foreign affairs, domestic politics, essays and miscellaneous articles. Section titles included ‘Capell Court’ (financial news), ‘The Whispering Gallery’ (gossip column), ‘Book of the Week’, ‘Mudies’ (short notices of books), ‘Vanity Fair’, and ‘Bohemia’, though sections varied across the life of the magazine. We were looking for articles that may have been by RLS, but time was short, so all we could do was to scan for likely items, then rapidly try to ‘taste’ them, all the time making notes.

After a couple of hours we went for lunch in a “caff” on the local row of suburban shops, chatting all the while about likely items that each of us had found; then we returned to take up the unequal race against time. Before we knew it, the clock was touching 4.30 and we were hurrying to order photoreproductions before closing time.

London: the conservative weekly…

According to World Cat, London is only held by two Libraries in the world: here in the British Library and at Yale—and the volumes in Yale are photographic copies of the ones here. So this was a precious document.

According to World Cat, London is only held by two Libraries in the world: here in the British Library and at Yale—and the volumes in Yale are photographic copies of the ones here. So this was a precious document.

Articles by Stevenson

We know that RLS contributed to the magazine from the very first number on 3 Feb 1877 (‘A Salt-Water Financier’ and ‘Mr Tennyson’s “Harold”‘) to November 1878 (‘Leon Berthelini’s Guitar’). The journal (edited by Henley from December 1877) did not itself continue much longer and the last number was issued on 5 Apr 1879.

Stevenson’s initial period of collaboration was short: from February to March/April 1877 (and in mid-May he writes, ‘I’ve been done with London, many’s the long day’ (L2, 210), but we know that he then contributed again from April to November 1878.

His seven items from 1877 had actually remained unknown for many years: Ernest Mehew identified six articles from that year in 1965, and Stevenson’s first published story ‘An Old Song’ (Feb–Mar 1877) was discovered by Roger Swearingen in 1982. The introduction to his edition of the text begins stirringly:

Few scholarly discoveries are as exciting as finding an important, entirely unknown work by an author one has been studying for years.

Articles not by Stevenson

Scanning through the volumes, we came across some articles that seemed witty, intelligent and well-written but could not be by RLS, or might be, but did not contain enough clues to merit the label ‘possibly by Stevenson’.

One of those that we momentarily considered a candidate because of references to Herbert Spencer, Darwin and ‘arboreal ancestors’, and which we then agreed to exclude (because of its frivolity and the lack of good clues), was a humourous piece on ‘The Evolution of Valentines’ (8 Feb 1879) which begins:

Evolution, Mr. Herbert Spencer tells us, proceeds always from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous. What could more beautifully illustrate this truth than the development of the Valentine?

Another whose style excluded it was an article on Mark Twain (1 Feb 1879). It was first considered because of the sentence ‘Boys like him because he has been a boy and hates the whole Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Budget system of education with a rich, boyish hatred’—since Franklin and Budget ‘The Successful Merchant’ are criticized in Stevenson’s ‘Lay Morals’ from the same period. But then we thought it could well have been written by Henley (the style is rather laboured: ‘hated […] with a rich, boyish hatred’), and he could have easily picked up these names from conversations with RLS. The following sentence I thought particularly successful:

Solemnly, soberly, positively, impossibly fantastic, exaggerating exaggeration; winging an idea of entirely unforeseen absurdity with words of the straightest, soundest, strongest pattern to be found in the dictionary or out of it; he takes possession of his opposite from end to end, hurries him from fit to fit of chuckling fondness, hurls him bodily into such abysses of laughter as are perilous to sound, and only leaves him when he is exhausted, and when, though he is not able to laugh any more, he is in a state of happiness not less complete than idiotic.

Another reason we decided against these two items is because they are both from February 1879 when we have no other information of RLS writing for the magazine.

Another item that attacted our attention was a witty put-down of a novel Done in the Dark (3 Mar 1877): well-written and handled with lightness, it could be by RLS—but it could also be by someone else. As I enjoyed reading it, I’ve put it at the end of this post to share with other readers.

Eleven possible London items by Stevenson had, before Mehew in 1965, been listed by George L. McKay (they had very probably been proposed by Beinecke’s Stevenson researcher, Gertrude Hills), but most of them do not look very likely: the two series ‘Husbands’, ‘Wives’, ‘Sweethearts’, ‘Flirts’; and then ‘Gossip’, ‘Scandal’, and ‘More about Gossip’—not only seem improbable titles for Stevenson but date from the period immediately after late April 1877 when we know RLS had thankfully abandoned the unwelcome forced work for the magazine. Indeed, they were more probably by James Walter Ferrier, as Henley writes in February 1877, ‘Ferrier will contribute ‘a series of “Humorous” – brief essays, on Sisters, Afternoon tea & et., like the Saturday mind [The Saturday Review; ‘kind’?], only humorous, & not witty’ (Atkinson, 44 & n). Another title listed in McKay, ‘At the Lyceum on Monday’, was shown by Swearingen (1980, p. 25) to be by Henley.

Only two of McKay’s eleven seemed possible candidates to us, for style, content and date: one on Balzac and the other on Villon. These we marked for for pdf requests and further investigation.

Another clue

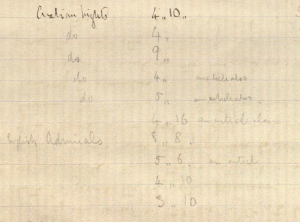

Arabian Nights….£4 10s

………do…………….£4

………do…………….£9

………do…………….£4 an article also

………do…………….£5 an article also

…………………………£4 16s an article also

English Admirals £8 8s

……………………….. £5 6s an article

……………………….. £4 10s

……………………….. £3 10s

On back page 16 of the Inland Voyage Notebook, RLS has listed payments received in 1878, in chronological order, ending with the sequence above which comes in the list immediately after the payment for ‘El Dorado’ (published May 1878). Although only the first five payments are specifically identified as ‘Arabian Nights’, the arrangement suggests that, apart from ‘English Admirals’ (published in the Cornhill in July 1878), these are 9 payments for episodes of the ‘Latter-Day Arabian Nights’ (published 8 Jun–26 Oct 1878), four of which also include ‘an article also’. (‘do.’ stands for ‘ditto’, i.e. archaic Italian—probably borrowed into English through accountancy—for ‘[already] said’.)

Without attempting to link these payments to exact numbers of London, the list seems to suggest that RLS was paid for four articles in London roughly in the period late June–August 1878, articles so far unidentified. The significance of this list was only realized after we’d had our day in Colindale and by chance it was a volume of the magazine we hadn’t had time to look at.

Second chance at the Beinecke

Luckily both RLA and myself will be at the Beienecke Library, Yale University, in October. We have already reserved their copies of London, and we intend to look through the pages for this period with an open but receptive mind.

Colindale, adieu

But to Colindale we shall never return. This pleasantly old-fashioned instititution will close forever on 8 November 2013, the building—admittedly, no jewel of modern architecture—will be pulled down and the land used for housing. The newspapers will be taken to a new state-of-the-art warehouse in Boston Spa, Yorkshire. Access to the collection will be in a new Newspaper Reading Room at St Pancras in the form of microfilm, digital copies or (if these are unavailable and the volume can travel), exceptionally, by the actual printed periodical. But eventually all the collection will be on microfilm or digital copy and the periodicals will stay locked inside their low-oxygen warehouse. (See reports in the Guardian and Financial Times.) So perhaps no-one will ever feel the delicately indented printed letters of London again.

Bonus track: review of Done in the Dark

I thought it was a nice example of deadpan irony, so I’ll share it here; it could be by RLS—but also by someone else, and nothing in the text gives a good clue to authorship.

Done in the Dark (Samuel Tinsley), by the author of “Recommended to Mercy,” is in many ways a remarkable book. That it has any merit as a novel we cannot conscientiously aver. There does not seem to be any particular story. The characters are all curiously unlike human beings. As for the dialogue, let this serve as a sample, the speaker being Joy, the heroine, who has just had the misfortune to lose her brother: “Have I no feeling, that I can talk so quietly of Archie’s death? Do I believe, have I understood, that never more in this world of the next will his warm fingers close upon my own, nor his brother’s dear kiss be pressed upon my cheek? Is it nothing to me that my father, to whom Archie was dear as was ever son to parent, is standing bare-headed, with a gray, pinched look upon his face?” &c., &c. And in point of reflection there are few, we imagine, but will feel the force of such a pregnant fancy as “even the restless robin feels that there is a time for all things, and perhaps (for who dares limit the extent of his faculties which God has given?) hails with thankfulness the moment when ‘tired Nature’s sweet restorer’ will close upon his bright black eyes in welcome slumber.”

From a heroine who could make such a speech as that one quoted above, while people with hooks and poles were dragging the river for Archie’s body, the reader is entitled to expect a great deal. He naturally feels a little disappointed when he gets nothing but a couple of more or less uninteresting marriages. How each of these is brought about we do not pause to explain. Indeed, we feel a certain delicacy on the subject, and had rather it were dropped, for our own sake as well as that of the authoress.

Nevertheless, the book is a remarkable book, and will well repay perusal. Having created a reflective and literary robin, the creation of a peculiar language was, comparatively speaking, as easy task. As a stylist, the authoress of Done in the Dark is not without merit. A sentence of fifteen, eighteen, or twenty-four lines is to her a mere everyday feat. The trick is skilfully done; a greater artist in the use of dashes and parentheses has never tried to write English; only the result is sometimes a little perplexing to the average reader. For it is not pleasant, after all, to come to the end of a sentence, and, after escaping a whole army of supplementary clauses, now beaming openly on you from between commas, now lurking for you behind brackets, now smiling at you across a stretch of dash, to find that you have forgotten the subject, and are as innocent of the import of your predicate as you are of the doings of Father Beke. But still, one feels that one is in the presence of a person who has original ideas on the subject of English composition, and one goes on one’s way with a vague feeling of respect.

The authoress is evidently well read. She has a fund of elegant quotation. We have seen that even her robin is acquainted with Shakespeare and other authors of merit. Her citations are numerous and varied. One or two are made to do duty twice as chapter headings; possibly an emulation of the Leitmotive of Wagner. But a person who is as familiar with Arsène Houssaye as with Shelley, with La Rochefoucauld as with Chaucer, ought to know better than to sanction such an impropriety as “Sweet bells jangles and out of tune.” What would Mr. Furnivall say?(London 3 Mar 1877, p. 116)